Prototype problems and challenges

The name P1800 is introduced

P1800 Convertible

Function test of the Italian prototypes

The tests continue in Baded-Baden, Germany

A modified four-cylinder engine for the sports car

The first official showings

The Brussels motor-Show January 16-27 1960

Other the shows during 1960

The British activities

The prototypes from Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors

The first prototype P1800-X1

The MIRA tests

The second prototype P1800-X2

The third prototype-X3

The first right-hand drive prototype P1800_X1 H

The final assembly of the P1800 is started

Preparation at Jensen Motors

Bodies by Pressed Steel Co. Ltd.

Quality control at Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel

The delivery inspection at Volvo Gothenburg

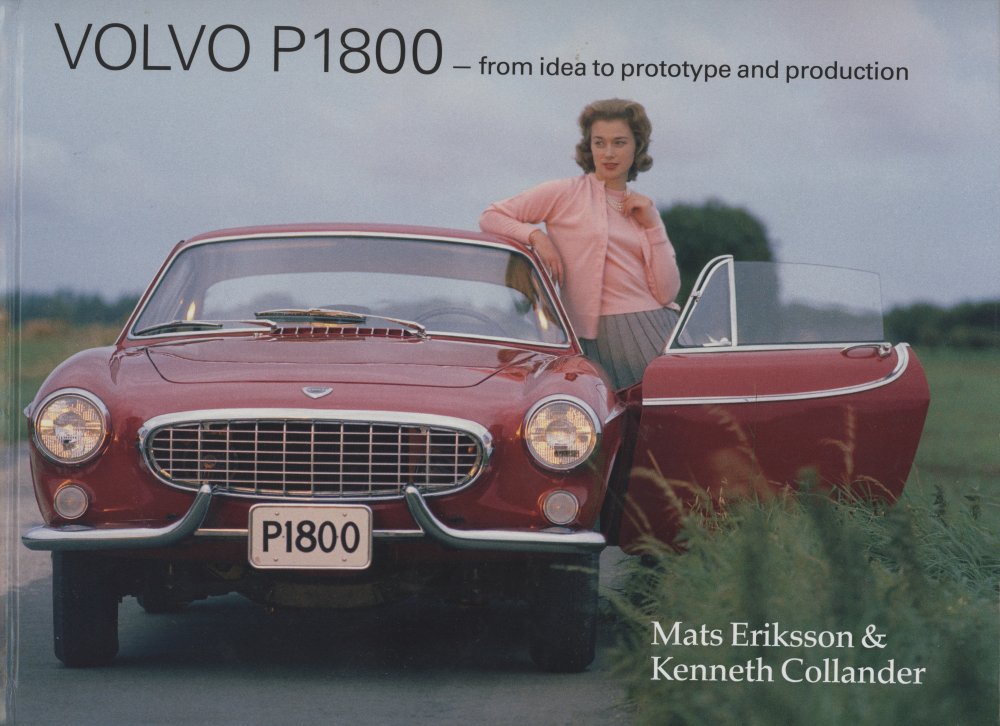

Photography for the first sales brochure

Differences between prototypes and production cars

The B18B designed and tested (162-165)

The production version comes to life in 1960

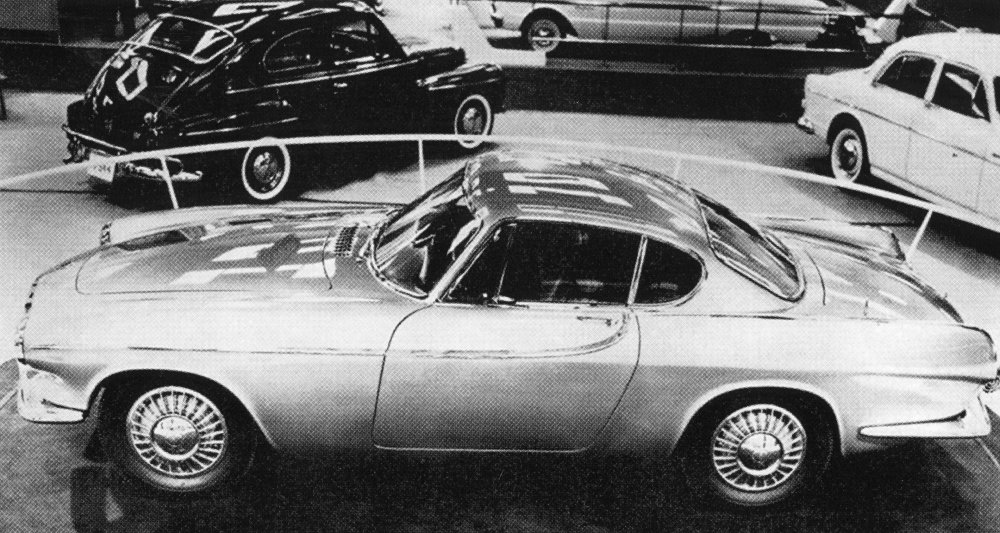

Chassis number 2 at the Brussels Motor Show

The type designations and their meaning

Prototype problems and challenges

There were many problems and challenges during the prototype stage. Volvo directors test-drove the P958 in 1959 and made their reflections. One of these reflections was made by Gunnar Engellau himself during a test ride on July 28, 1959, when he had a lot of remarks and views. Among other things, he pointed out that the ventilation system did not work satisfactorily. The system was basically identical to Amazon’s, but there were no opportunities to increase its capacity due to lack of space. Engellau also noted that the ventilation windows only sucked air out of the car and that no new air was allowed in. This was then corrected on the production cars as the axis of rotation of the windows was changed. Engellau also had comments on the side windows and elevator functions that involved far too many laps between the outer positions, which was also corrected on the production cars. Other examples were that he found the glove compartments in the doors and the location of the handbrake less suitable. This event represents in a very clear way how hectic it was during this time. Volvo Director Gunnar Engellau smoked a pipe and one of his reflections during the test drive of the prototype P958-X1 was that the car required a much larger ashtray that allowed room for a pipe. The ashtray did not hold his smoking pipe, even for cigarette smokers, the ashtray was too small. Therefore, the specification was quickly changed and the Volvo’s Styling department in Sweden constructed a new and bigger ashtray that would satisfy pipe smokers”. Åke Björksund was then personally commissioned to fly over to England with the dashboard and deliver the panel to Pressed Steel after travelling the last bit from London to Oxford in a taxi. Another problem that was faced in 1959 during the construction and start-up of production was the double image seen in the rear view mirror. It arose due to reflection and strong breakage in the strongly inclined and thick rear window. It became Vallin’s task to minimize the problem, which resulted in the rear window manufactured by Pilkington having to be made thinner.

On one occasion, both Helmer and Pelle Petterson came to visit England. After the visit, changes were made to the car’s electrical system. Later, Svante Simonsson also came over to Jensen Motors and became aware of the state of the project, leaving Jensen Motors with some concern. To try to get Eric Neale to sit still for a while and go through the situation with drawings, Gösta Vallin asked that Tord Lidmalm come over and make Mr. Neale understand the seriousness. It was for Vallin a memorable day when Tord Lidmalm, Eric Neale and Vallin sat in Neale’s office, a small scrub with no windows or ventilation and which really only accommodated two people. Lidmalm sat with a list of details and asked with infinite patience about when every detail would be finished and Mr. Neale confidently stated a date at first. They started at nine o’clock and held a short break for lunch until 22.00. By then, Mr. Neale had eventually understood that too many drawings had fallen into lumps near the end date. Mr. Neale realized that the situation was awkward and that he needed help. Volvo had helped with occasional reinforcements, but now Volvo had to invest more and more.

Late in 1959, Volvo identified several areas of work that would require extensive control and had contact with Jensen more or less continuously. Examples of this were delivery monitoring of English details where Volvo believed that it should be made clear to Jensen that they were responsible and that Volvo’s purchasing department should only intervene in emergencies. A concern was the spare parts area and whether Jensen would be able to provide documentation in time for how Volvo would buy spare parts that were part of complete details from Jensen’s subcontractors. Other areas were customs issues, change services, shipping issues, and billing and delivery issues.

Åke Björksund spent a lot of time in the British Isles during 1959 and 1960 and, like Vallin, emphasizes that it was a busy period. The assignment to assemble the sports car was a new experience and a major upheaval for Jensen, which required a great deal of work from all parties involved. Björksund acted as direct support in the continued work on site both at Pressed Steel and at Jensen Motors. Björksund was responsible for, among other things, the transfer of knowledge and experience that continuously took place between Volvo, Jensen and Pressed Steel during the early construction stage. Björksund spent a total of about nine months at the Jensen plant, interspersed with many trips to Gothenburg for reporting and development discussions, and then on the next trip to England to be able to give feedback to the English and contribute to continuous improvement work in production.

The name P1800 is introduced

During 1959, a lot of time and resources were devoted to working out the content of the sports car’s specification. Among other things, the division of responsibilities for details was changed, which in some cases was transferred from Jensen’s to Volvo’s commitment. The first time that the name “P1800” appears in an internal Volvo document has been found in a meeting minutes from a meeting on August 18, 1959 where the arrangement of preparations for the start of production for the sports car – the P1800 – is discussed. On the occasion, the issue of a possible sunroof was discussed, which was rejected because it was considered inappropriate. It was also decided that two of the three Frua-made prototypes would be urgently rebuilt for future exhibition purposes. At the same time, it also emerged from the discussions that took place at the meeting that Volvo expected that about 80% of the P1800 cars manufactured were estimated to be “shipped west” to North America. On September 10, 1959, T.G. Andersson informed Director Engellau that Volvo would probably be able to cope with the duty exemption for “larger identifiable details” (engine, gearbox, radiator) that Volvo would send to England from Sweden. Moreover, at this time, it was clear that Pressed Steel’s first No. 1 body prototype was delayed two weeks until October 14

During the summer of 1959, Volvo requested a quote from Pressed Steel for a right-hand drive variant of the P1800, which was then delivered relatively quickly and Volvo accepted the quote, which amounted to £9406 for the various pressing tools. At a meeting on 21 November, Director Engellau decided that a right-hand drive car should be put into production but that it would in no way interfere with the development of the left-hand drive variant. It was aimed at a right-hand drive car being put into production from April or possibly July 1961. In reality, however, it came to be much later, in February/March 1962.

Volvo P1800 Convertible

According to the original order from Volvo’s management, Volvo engineers were to give the P1800 a design that allowed the sports car to be manufactured in convertible design with the canopy and, as an alternative, a hard top made of plastic instead of the canopy in winter use. It was initially desired that this variant would be available as early as spring/summer 1961 and already in the specification Pressed Steel was instructed to design the body to allow for an easy addition of the necessary reinforcements to the body for a convertible. Then the discussions around this quieted down, but later in the summer of 1961 Volvo’s plans for a convertible would come back to life. Then the head of Volvo’s technical department, Director Tord Lidmalm, contacted Pressed Steel’s Sales Manager Mr. C. Coynes to order documentation for estimating the schedule and costs that would be related to Pressed Steel’s work on the design and development of tools for a convertible. This included a request for when a finished car could be completed. Volvo intended to raise the question of whether the convertible should be or not be at a board meeting in August 1961 and therefore demanded a swift position from Pressed Steel.

In October 1961, Pressed Steel delivered their documentation to Svante Simonsson together with a brochure describing their proposal with a quote. Volvo’s intention was that a version of the P1800 as a convertible could be launched in April 1962 and production started in April 1963 with an expected maximum production of 100 bodies per week. Simonsson instructed Tor Berthelius and the passenger car drawing office to conduct an investigation into the suitability of proceeding with the manufacture of a P1800 convertible. The investigation focused on tool costs and included changes to everything from the front fender, sill boxes, rear cover, windshield frame and windshield pillars to beams, various reinforcements at the frame/middle board and rear seat risers. Volvo so far did not have much experience of the demand for the coupe design and some uncertainty and caution therefore characterized Volvo’s trade-offs. Berthelius suggested that a market analysis should be made and pointed out that if a decision was made on the development of a convertible version, it was important to instruct Pressed Steel to develop a test body so that strength tests could be carried out. The next step would be to request that Pressed Steel produce proposals for the construction of the canopy, either a hand-operated or a hydraulically operated one. Berthelius identified that the weight gain could be significant, which would of course have a negative impact on the car’s performance. According to Pressed Steel’s quote, the tool cost would amount to approximately SEK 1.5 million, to which other costs for the construction of other parts, other tools, two prototypes and testing including long-term tests would be added. Together, the cost would end up at around 2 million SEK

After Gunnar Engellau took part in Berthelius’ investigation, it was judged that it would be very expensive, risky and at all doubtful that Volvo would complete the investment in a P1800 convertible, so there were none of these plans. It is very likely that this case was certainly adversely affected by all the time- and resource-intensive work that Volvo devoted to overcoming the other body problems at Pressed Steel in 1961.

A couple of years later, one of Volvo’s dealers in the USA, the company Volvoville in New York, took up the idea of producing a P1800 in convertible design and about thirty copies were made between 1963 and 1967. A company in England called Radford also converted a few Volvo 1800S to convertible version.

Volvoville

Irv Gordon says: “I have heard that Volvoville made 57 convertibles including the 15-20 experimental cars that were later scrapped. Some of these had been involved in accidents or otherwise destroyed. At the time I bought my red 1966, Volvoville had fitted a huge map on the wall with pins marking every place where a convertible had been sold” When a good method was found to convert the cars, carry out body reinforcements and manufacture soft tops, the experiments stopped. Next, the company ‘International Auto Painting’ was hired to refine the body conversions. All convertibles sold to customers were done by ‘International Auto Painting’. With their solid body reinforcement, no problems were experienced with self-opening doors that can be a problem with homemade conversions.

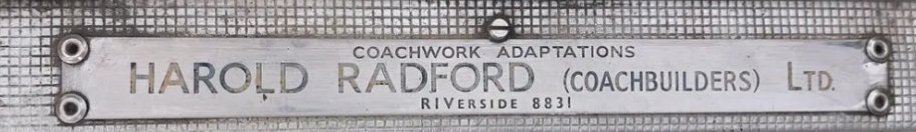

Harold Radford 1800S Convertible

The London-based company Harold Radford Coach builders operated in Melton Court in South Kensington, London since the 1940s and were well-known Roll-Royce and Bentley dealers. They developed and niched the business towards specialist estate car builds, mainly Bentley and Rolls-Royce. Many associate the name Radford with their acclaimed work on luxury versions of the Mini brand.

A new pearl white 1800S with chassis number 14459 was delivered from Sweden to England on March 26, 1965 and was converted by Radford and completed in late 1965.

Below a photo of the car during the conversion at Harold Radfords in London.

As the car was ordered through a Volvo dealer, the result was as close as you can get to an official Volvo 1800S convertible

Information varies as to how many 1800S were converted by Harold Radford but according to Chris Gow who administers “The Radford register” a single 1800S was converted”. A further conversion is said to have been ordered, but apparently never built as Harold Radford ran into financial problems in mid-1966. According to other information however, Harold Radford is said to have made four conversions on behalf of an English Volvo dealer. All four are said to have been white cars of the 1965/66 model year. Rumor has it that two of them were destroyed by fire, but this has not been confirmed.

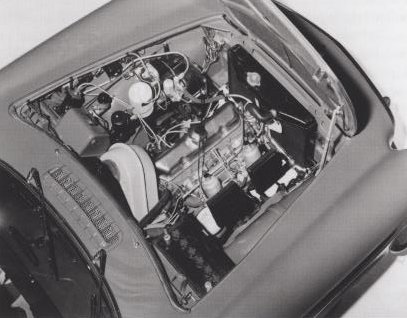

Function test of the Italian prototypes

While the body tools were being prepared in England, Volvo tested the Frua-built prototypes to determine the chassis specifications and in 1959 the P958-X1 was tested at home in Sweden for tyres, road characteristics, noise, comfort and ventilation, among other things. One person who was involved in conducting test drives in Sweden at the prototype stage was Tage Hansson. He says that extensive special tests were done by Volvo’s experiment workshop with two of the Italian-built prototypes. Test drives were made with cars without Volvo emblems on public roads, e.g. at Lekare kulle between Kungsbacka and Åsa. At that time, free speed prevailed outside densely populated communities, which facilitated achieving top speeds without risking legal penalties. They drove both day and night with a focus on power and brake tests. After these special tests, long-term tests were taken. These tests were carried out by staff from the car laboratory (laboratory/development/testing) who were under Åke Larborn. The car laboratory consisted of two different departments, one of which was passenger cars with Rune Fritsby as manager.

After conducting tests at home, it was decided that further tests should be done abroad. In early April 1959, Rune Fritsby and Sture Agård conducted an overall test and assessment of the characteristics of the sports car with the second Italian prototype P958-X2 in the Black Forest in southern Germany.

Sture Agård remembers that the testing work with the P958 came as a sudden surprise. One day, the P958-X2 was shown to him where it was parked in a garage of an apartment building in Biskopsgården. Discretion was of course important and you had to sneak the car out at night to the tests. First tests performed extensively cooling, temperature and speed at full throttle. The test car then had to tow a weight that often consisted of a Volvo PV831, with which the speed was regulated, so that the tests would take place under maximum load at different speeds. Ideally, this test was carried out during a four-km long straight on a horizontal road, in the Gothenburg area this occurred, among other things, on the road to Kungälv. Other tests performed were of brakes and cooling as temperatures were measured in the cooling system. Since there was no established method or documented procedures for the various test steps, the test staff worked independently with great responsibility. The population and police looked favorably on these exercises, which could sometimes involve both high speed and perilous moments.

The tests continue in Baded-Baden, Germany

The P958-X2 was transported by Volvo’s transport department in a covered truck to Paris where Rune Fritsby picked it up and provided the car with French red/white tourist car plates. Then Fritsby drove the car on by his own machine to Baden-Baden in the Black Forest area of Germany. There awaited Agård, who had driven down from Sweden to the same place with an Amazon. The Amazon was loaded with tools and various components for testing and included shock absorbers, rubber bushings, B16 engine parts and a variety of tire types. It also included anti-roll bars in different dimensions as well as the “5th wheel” that measured speed and braking distances. Agård remembers coming down to Germany on March 9, 1959, and then nearly six months were spent there with a short break for Easter celebrations, when they traveled home to the families. The hotel named Kurhaus Plättig was already booked when Agård came down, but the hotel unfortunately had unsuitable garage spaces. Fortunately, the hotel host also had a private garage, which could be locked separately, which Agård and Fritsby had to dispose of. An agreement with the hotelier guaranteed discretion – he would “ignore” the two “French” guests in order for as little attention as possible to arise. The hotel owner did not cope with this, but told an acquaintance and suddenly a man was out among the garages with a camera trying to get a picture of the “secret” car. It all ended with Fritsby and Agård giving the hotel owner a hefty scolding.

Volvo chose to place the tests in West Germany for reasons of confidentiality, to be left alone for curious glances and for the opportunity to drive on the Autobahn. They were tasked with free-hand optimizing the characteristics of the car. In Sweden at this time, there were not very good conditions for trying out a new sports car, which meant that you had to apply to the Autobahn instead. It was intended to verify that the car was indeed capable of its high performance. Registering the car in France also proved to be a good idea, as the majority of the testing would take place in what was then West Germany. It was only a little over a decade after the Second World War had ended and the aversion between Germans and French was still palpable. “We even had a pack of Gauloise brand French cigarettes on top of the dashboard, clearly visible from the outside to enhance the French impression. In this way, we got to be left alone from an otherwise curious local, says Rune Fritsby.

No special test tracks could be used, it would probably draw far too much unwanted attention to their secret exercises. Rune and Sture were cautious, although the motor press of the 1950s was by no means as hysterical in digging out the car industry’s news compared to today. The prototype, for example, was never masked. It was important not to affect the characteristics of the car with masking. In contrast, all emblems that could gossip about the P958-X2 being a Volvo had been masked or removed. It was pretty exciting with all the secrecy during this time,” Rune recalls. The Amazon and the prototype were never shown at the same time, one was always in the garage, so that no connection between the P958-X2 and Volvo could be made. The Hotel Kurhaus Plättig was used as a base for several months and the Black Forest area with its winding roads was very suitable for test drives. They were careful and sneaked away on their test rounds and moved all the time so as not to attract unnecessary attention. Once on the road, there was no problem. It wasn’t exactly a long test run. It wasn’t needed either. Fritsby and Agård were already experienced test drivers and quickly discovered what was not good.

Rune Fritsby says: “Yes, the sports car was a fun car to drive, especially when compared to other vehicles.” Meanwhile, in West Germany, we had access to several of the competitors’ cars, including the Mercedes 190 SL and Austin Healey and none of these came close to the sports car in terms of driving pleasure and road characteristics. The Mercedes was “frankly” disappointing. The Mercedes-Benz 190SL Cabriolet was perceived as so torsionally smooth that road characteristics were negatively affected.

The rear wheels were not allowed to drop when sharply cornering at high speed. Amazon had Michelin diagonal tires, but these were unreliable when cornering at high speed as they could suddenly release traction without warning. One innovation, which is said to have first been launched by Michelin, was the radial tyres, which were significantly better at this point. At an early stage, it was discovered that the sports car would gain a lot from having the new radial tires instead of diagonal tires. The cornering characteristics of the car were significantly improved with these tires and the carriage also became quieter inside. Two types of radial tires were tested: Michelin X with steel cord, which was used by Citroën, among others; and Pirelli with textile cord. Both types were superior to their competitors, but the Michelin X did not cope with the sports car chassis very well because it was too stiff longitudinally for such a tire and much of the road noise propagated into the passenger compartment. Over time, the Pirelli Cinturato, a textile radial tire of 4.5 inch rims, was chosen for the sports car. The tire change meant that the chassis, which was basically taken from the Amazon, had to be rebuilt to cope with the new radial tires. Both in the front and rear carriages, the bushings were softened. At one point, the couple Fritsby and Agård drove around German cobblestone streets, as a kind of “shaking test” to test the chassis. They drove back and forth many times. Finally, they got into a dead end, when they were about to back out it did not work out, because the gearbox had broken.

Fritsby and Agård were diligent with the use of the so-called “5th wheel” and the tests became increasingly tough. During one of the test rides on the partially closed highway, they were pursued by a German BMW. They thought, of course, that it was a civilian police car that had caught sight of them and that it was only a matter of time before they would get caught. Instead, it turned out that it was a road engineer who had pursued them because he believed that Fritsby and Agård were out conducting an evaluation of his work results. However, he disappeared quite quickly when he realized that they were in fact car testers from Sweden.

There were great demands on the brakes in a sports car. The P958-X2 was equipped with Amazon’s drum brakes on all four wheels. The brake pads in the front wheels were so-called “plus slopes”, equipped with double wheel cylinders with very high servo power. With this braking system, the risk of skewing between the right and left wheels increased, which could make the car dangerous and unsteerable when braking heavily from high speeds. Together with a softened chassis, this would overall make for an unsafe car. Rune and Sture were both surprised and worried when this was discovered. In the vicinity of the Black Forest, a new highway was built between Basel and Karlsruhe. Parts of the highway were paved and clear, but still closed to regular traffic. On these stretches of road, the more extreme characteristics of the car could be tested, such as maximum speed, acceleration and braking characteristics. They came back to the closed highway several times. The exams became harder and harder. At first they drove carefully, then increasingly boldly. Their fears came true, all of a sudden at a sharp braking from high speed what must not happen happened, the car pulled very obliquely and the whole thing was about to end with a crash of the P958-X2, but luckily both the test driver and the car survived. Both Sture and Rune noted that the use of Amazon’s drum brakes on the front wheels of the sports car would be out of the question. Volvo therefore began to investigate, together with Lockheed and Girling, the conditions for equipping the sports car with servo-assisted braking system with disc brakes on the front wheels.

In the winter of 1959, work continued on brake tests at home in Sweden, but brake tests had to be carried out on dry road surfaces, which was difficult at home in Gothenburg during the winter. In order to have the opportunity to perform brake tests on bare ground, Agård and two mechanics went in two disc brake-equipped Amazons as test cars by ferry to Frederikshavn in Denmark. They didn’t get any further than that as the roads had been closed due to heavy snowfall. They tried to get further south by going after plow trucks, but without success. Agård was forced to put the cars on a freight train with destination Flensburg, but there was also snow on the roads and the test team had to continue on down to South Germany where the tests could finally be carried out. In the end, Girling’s braking system with vacuum amplifiers and discs was chosen, which was manufactured by Pianoforte Supplies Ltd., Northampton, England. The calipers had two small pistons on the outside and a solitary large one on the inside.

At the same time, the styling department at Volvo in Gothenburg was working on the design of a new dashboard and none of the other cars were available in Sweden during this time. Therefore, Åke Björksund had to travel down to Germany to on the P958-X2 template and draw up profiles for the dashboard and steering wheel suspension

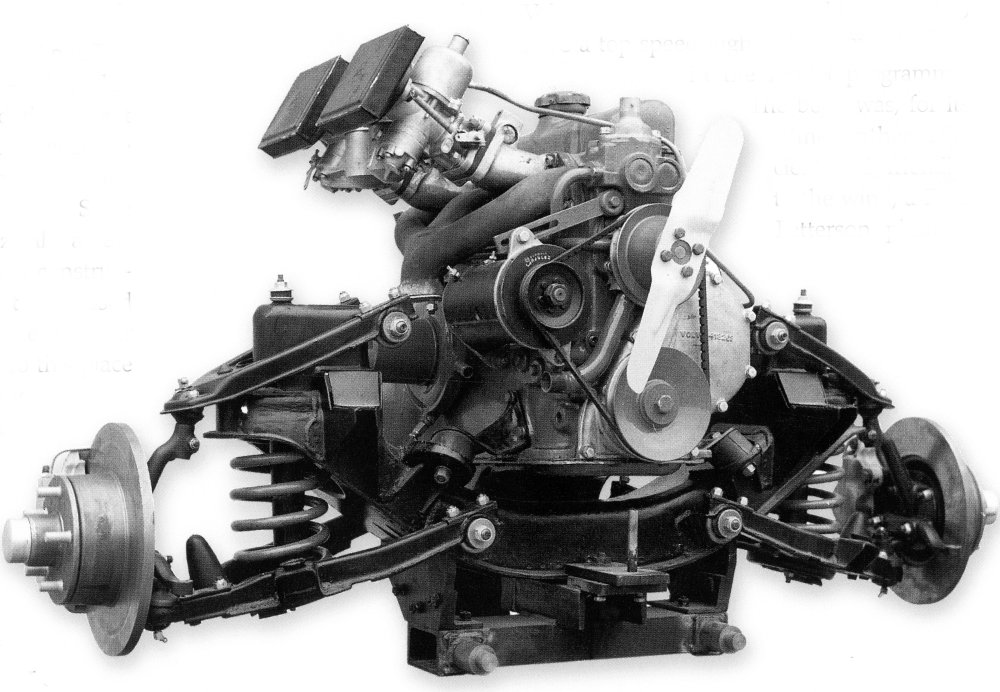

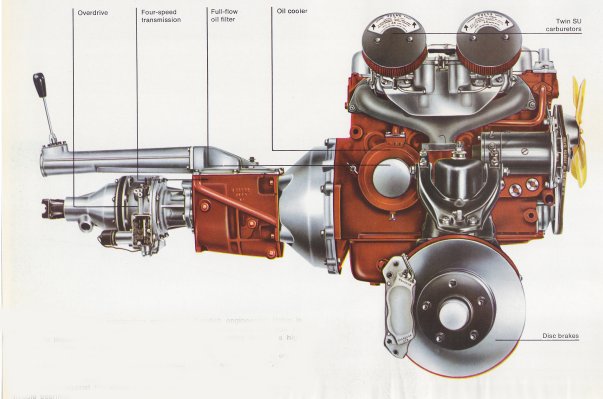

A modified four-cylinder engine for the sports car

Volvo’s management expected the new sports car to have a top speed that was higher than that of any other car in the model range. At that time, the body was designed unusually efficiently with low air resistance, all according to Pelle Petterson’s philosophy that the car should be “kind to the wind”. Among other things, due to the given bottom plate, the design had become relatively heavy. The car therefore felt relatively lethargic despite the B16B sports engine, which developed 85 horsepower from 1,583 cm3, but the low air resistance still allowed the car to reach top speeds of 170-180 km/h.

Volvo had foreseen the need for a stronger engine and already in 1957, at the same time as the B16 engine was put into production, some preliminary studies and experiments began with B16 engines produced with 5-layer crankshafts, which with their long service life had surprised Volvo engineers. Volvo also had various Italian engine experts, among others. Abarth tuned volvo engines that were tested in Amazons. The conclusion of the tests was that Volvo decided to develop a new engine under its own auspices.

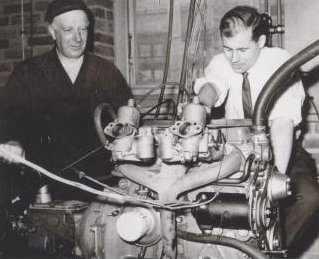

In October 1957, the Volvo Directorate summoned its engine design office to a meeting where technical director Tord Lidmalm sketched out the conditions for an engine for the planned sports car, which resulted in Volvo’s technical committee deciding on October 12 that an amended four-cylinder engine should be built for the sports car. Since it was developed from the existing B16 engine, it received the working designation X2-B16.

The initiative for the creation of the X2-B16 came as a result of the project with Volvo Sport and the engine came to be designed under the guidance of the engine department’s chief engineer John Stålblad. Here Erling Kurt and Åke Zachrisson had leading roles. Among the conditions that applied were; new four-cylinder engine with five frame bearings and the possibility of expansion to larger cylinder capacity, higher power than on the sports engine B16B, the least possible weight gain and, of course, low manufacturing cost

The day before Christmas Eve 1958, Åke Larborn, head of the development laboratory, informed Gunnar Engellau that testing of the sports car had begun and that the B18 engine in sports design was expected to be available by the end of March 1959. One of the Italian prototype cars was expected to be completed in February 1959 and what would then mainly be tested was cooling, brakes, suspension and shock absorbers. For prototype P958-X1, functional tests were planned for two months, one month of shaking test and long-term test for nine months. The P958-X2 could be put to the test immediately. Functional tests and long-term tests were planned to be carried out on the continent, while quake court tests could be carried out at MIRA in England, possibly with the help of Pressed Steel.

In June 1959, the issue of engine selection for the P958 was again discussed before formal decision was to be made. After an in-depth discussion at the very highest level and after analyzing both the advantages and disadvantages of the B16 and X2-B16 in the sports car, Gunnar Engellau finally decided on June 12 that the sports car should be equipped with X2-B16. From the technical side, it was pointed out that the B16 engine had been preferable in the early days and that the transition to the X2-B16 would ideally take place only later.

The Italian prototypes had already been tested in 1959 and towards the end of the same year the first English prototype cars (P1800-X1) finally began to be completed at Jensen Motors. Larborn’s planning included initiating an intensified testing program of the P1800-X1 from December 1959. Like the Italian cars, functional tests were again planned for two months, trembling tests for MIRA for one month and finally long-term tests for nine months.

The first official showings

It took two years to prepare the sports car for production in England and now the sharp situation awaited Volvo. At the end of 1959, Volvo began to seriously prepare for displaying the first English-built prototype to representatives of the Swedish press, which was planned to take place in early January 1960. Jensen Motors was in the final phase of completion of the car in December 1959, but work was delayed. According to the original plan, two Jensen-built prototypes would be ready for use by Volvo in marketing operations and in the planned test program in the early 1960s.

Due to the delays in England, Volvo had to change its plans and the cars it chose instead to show off publicly were the Frua-made prototypes P958-X2 and P958-X3. In order to pre-prepare the sports cars for official viewing, a detailed review and restyling of them was made. These cars differed in several essential respects from the upcoming production execution. Tor Berthelius compiled these differences on November 27, 1959. Both cars were equipped with B16B and 6-volt electrical systems. Even the location of the wheel capsules and hand brake lever under the dashboard differed from the production version. In addition, sealing strips were missing on the doors and the side windows could not be cranked down completely. Several buttons and controls on the instrument panels were not acceptable at the time of the inspection, either from the point of view of safety or convenience. Other differences were the size of the ashtray, the storage compartments in the doors and the light plastic on the top of the dashboards, which gave unwanted reflexes. Berthelius finally commented that the yellow P958-X2 would be repainted and equipped with completely new upholstery and new mats, as well as the silver-grey P958-X3 would be repainted and this would be done before Monday, December 21, 1959, when the cars would be ready for display.

Before the cars were repainted, a total rebuild of the rear sections of both the P958-X2 and P958-X3 was carried out. They got basically the same design as the first Jensen-built prototype (P1800-X1) had. The modifications on the rear end consisted of mounting a Volvo text, changing the number plate lighting, and removing the recessed number plate holder and exhaust pipes that ran through the rear of the body. The original rear lighting characteristic of the Frua-built prototypes was retained. The P958-X2 was then rebuilt once more and then got the same design on the rear end as the third Jensen built prototype, i.e. almost a series version.

The Brussels motor-Show January 16-27 1960

Around the turn of the year 1959–60, Volvo published additional information about the P1800 sports car accompanied by pictures of the Frua prototype P958-X3. In these pictures, the carriage has the rebuilt aft section. There was great interest in the sports car and Volvo decided to show off the P958-X2 at the 40th Motor Show at the Palais du Centenaire in Brussels between 16 and 27 January 1960. The presentation was successful and orders for three carts are said to have been registered already on the first day

Volvo presented the sports car to the world as follows:

VOLVO’S NEW SPORTS CAR

is shown for the first time

at the Brussels Motor Show

Earliest publication date on 14 January at 24.00 CET

The latest addition to AB Volvo’s manufacturing program, the new Volvo P1800 sports car, will be presented for the first time at the automobile exhibition in Brussels, which opens on January 16. The new sports car is mainly based on the standard elements included in Volvo’s current passenger car program. For the sports car, however, a new engine of 1,78 liters and a power of 100 hp (SAE) has been designed, which gives the light car a particularly excellent acceleration and high top speed. The gearbox is based on the same four-speed type that is currently found in the Volvo 122 S and PV 544. However, it has been redesigned and dimensioned for sports car use. Optionally, electrically operated overdrive can be obtained. The car has servo-operated brakes with a conventional drum braking system on the rear wheels and disc brakes on the front wheels. The sports car will initially be developed left-hand drive, but it is also planned to introduce a right-hand drive version. Like other Volvo cars, safety has been taken into account the most. The car is thus equipped from the factory with brackets for seat belts, mattress pad on dashboard and sun visor, windshield flushing, etc. Volvo P1800 has a particularly excellent instrumentation beyond what is common in standard passenger cars, including tachometers, oil temperature gauges and trip meters.

Serial production at the end of 1960

The new sports car is expected to enter series production in September 1960. As of January 1, 1961, the production rate is estimated to be around 100 cars a week. The body has been designed in Italy, but its production will take place in England, at Pressed Steel Ltd. Assembly of the car will also take place in England. The reason why these works have been placed abroad is that the entire Volvo available capacity in Sweden in these areas is utilized for the company’s current manufacturing program. The new sports car, the Volvo P1800, will be sold both in Sweden and in the export markets where Volvo is represented. For further information of a technical nature, please refer to the attached detailed specifications

Other shows during 1960

The P958-X3 is said to have been shown in Copenhagen between February 26 and March 6, but this information has not been confirmed. In any case, Volvo confidently shipped the P958-X3 to the U.S. in a box for exhibition at the fourth in the order of the International Auto Show at the Colosseum in New York between April 15 and 23. There, on the third floor of booth 301, the car was displayed along with the PV544, 122S, and ÖV4 (Jakob made 1927). Volvo’s stand is said to have been the largest on the entire floor. In the nearest stand, the car brand Checker was shown, but that stand made up only one-sixth of the size of the Volvo stand. Opposite Volvo on the other side of the aisle, in booth 302A, Chevrolet was shown and in booth 302, Ford was shown, but Ford’s and Chevrolet’s surfaces were together as large as the entire Volvo surface.

Volvo itself considered the P1800 as one of the great numbers in the Colosseum, and the car aroused interest not only in the exhibition visitors, but also in people in such a remote place as Antarctica. Members of a U.S. Navy group wintering at McMurdo Sound in Antarctica were sent descriptions and photos of the cars on display at the New York show. After they had spent hours going through the brochures and for many more hours discussing the advantages of the various cars, the group under Lieutenant Commander B.W. Warren finally agreed that the Volvo P1800 was the biggest sensation in the exhibition. The result was a telegram that read as follows: Several takers of the wintering group in Antarctica interested in the Volvo Sport Coupé. Asks to know if the car should be produced in the manner stated in the newspapers and the price. B.W. Warren, Lt. Cmdr. Volvo’s response was: Thank you for your telegram this morning. Volvo P1800 the big star at the International Auto Show in N.Y. Coliseum last week. All newspapers and magazines agree on this. Production begins in September, the car can be had this fall. Approximate price $3800. Would be nice if you bought one. Shall we ship it to McMurdo Sound or will you come and get it? The job as a dealer in McMurdo Sound is still vacant, if you want it. Åke Högman, director Volvo Import, Inc.

In addition, the P958-X2 was exhibited at the International Motor Show in Geneva (March 1960), the Grand Palais in Paris (October 6–16), the Earls Court in London (October 19–29) and at the Palazzo Esposizioni al Valentino in Turin (November 3–13). For the Paris Motor Show, the rear section of the P958-X2 was rebuilt once more, in a design similar to that of the third Jensen-built prototype (P1800-X3), which was the closest you could get to a series version. After the three Frua prototypes served as a link between drawing boards and production, they were considered by Volvo as consumed and some employees were then given the opportunity to buy them off, although with some reservations. Volvo engineer Åke Björksund was the first private owner of one of these prototypes, namely the steel grey P958-X3.

The British activities

The year 1960 was mainly devoted to completing the Jensen-built prototypes, carrying out tests and changes, establishing final drawings and specifications, and carrying out final preparations for the start of production that were scheduled for the autumn of 1960. However, the clouds of worry began and tough times awaited in the latter part of 1960. Problems awaited from the north in the British Isles.

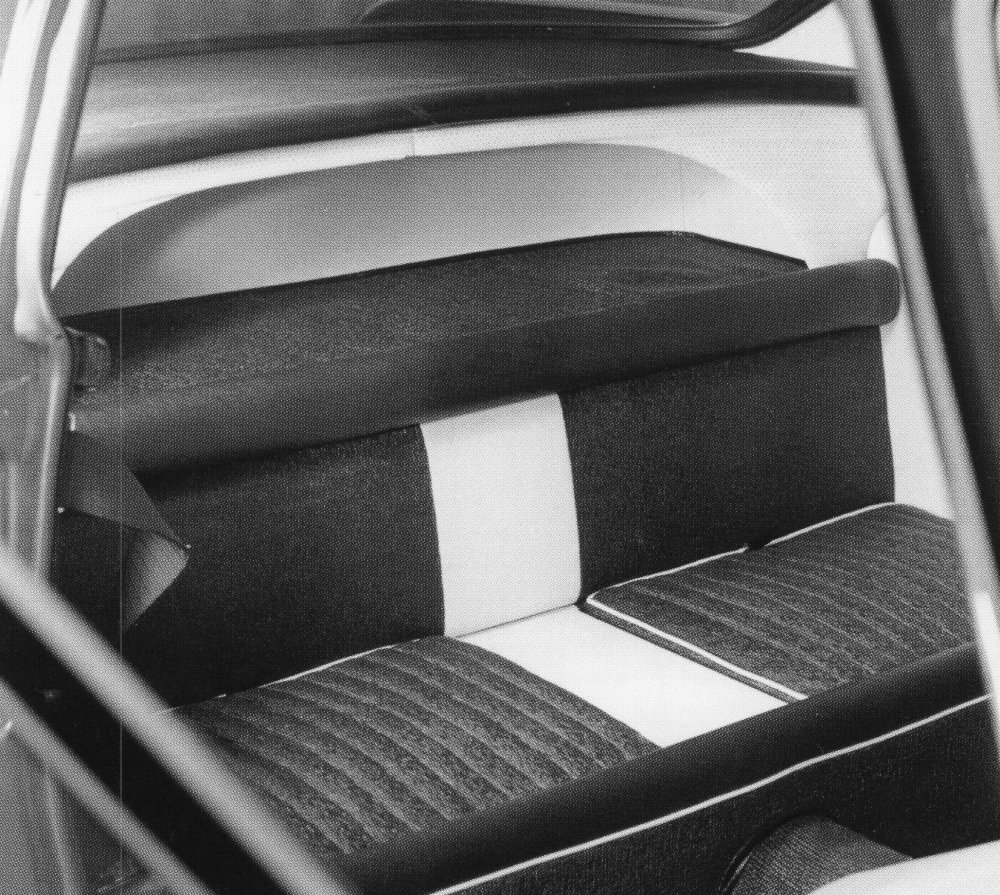

In early January, Volvo expected production tools for manufacturing the body at Pressed Steel to be ready around September 30, 1960. In a letter from Uno Gunnelid at Volvo’s planning department in Gothenburg, the three Jensen-built prototypes are mentioned at an early stage and they are called X4, X5 and X6. It also states that Pressed Steel intended to produce a maximum of five bodies for the pre-production cars during the last eight weeks before the start of production, consequently between July and September. In May 1960, engineer and coordinator Thorsten Laurent gave the go-ahead to Pressed Steel to start production of two pre-production bodies complete on front axles during August and two more bodies during the month of September. Four pre-production bodies were manufactured by Pressed Steel and delivered to Jensen Motors during the period August 15 and September 30, but the pace of production of the finished cars was delayed due to the fact that Jensen Motors largely lacked parts for test assembly. Two of the pre-production bodies were ordered to be red with white interior and the other two white with red interior. It is probably these bodies that were used on the series cars with chassis numbers 1–4, as the specification fits well with the design of the pre-production bodies and the upholstery of the finished cars; chassis numbers 1 and 3 turned white and chassis numbers 2 and 4 turned red.

At the same time, Volvo sent a formal order to Pressed Steel amounting to 9500 bodies, according to the original 1959 contract, subject to the remaining 500 bodies that could be ordered in a right-hand drive version. However, a decision on the quantity of right-hand drive cars had not yet been made. Production deliveries of finished bodies could then, at best, start in October at a rate of between six and ten bodies and then increase the pace to about five to six bodies per week during November and about five to six bodies per day during the month of December. If this had been followed, it would have resulted in a total of 150 bodies being completed in 1960. As of May 1961, Pressed Steel was counting on being able to manufacture 200 bodies per week, which would mean that before the end of 1961, about 7300 bodies had been manufactured. These quantities would later prove to be completely exorbitant.

In January 1960, it turned out that the final drawings for the car were greatly delayed. This was stated at a meeting between Tord Lidmalm and Gösta Vallin from Volvo and Mr. Neale and Mr. Hubbard from Jensen Motors. At a meeting on January 25 between several representatives at the highest level from Volvo (Gunnar Engellau) and Jensen Motors (Alan Jensen) that took place at the West Bromwich plant, it was decided that the car would be produced in three different colors; off white (Ivory), grey (like the first Jensen prototype) and red (like the second and third Jensen prototypes) and in order to later replace any of these, a light blue color would be prepared. When it came to armrests, upper door sides and dashboard, it was decided that these should be black regardless of the other colors of the interior. On this occasion, it was also decided that the second Jensen prototype would be red, the seats and hubcaps were approved, but the rear number plate lighting that was proposed to be integrated with the bumper was approved and demanded rubber mat in the trunk. Engellau demanded larger VOLVO lettering on the rear stem, better fit on the fuel filler cap, larger windshield wipers, the choke slider named, and smaller size of the boxes in the grill.

During the spring, Gösta Vallin devoted a lot of work to contacts with Pressed Steel to sort out and together with them decide on the final execution of the car’s details. This ranged from the hood locking device, radiator, window crank mechanism, seat belt attachment to the placement of the instruments on the dashboard. After these decisions, the necessary drawing material was then created and the changes were many. In May, Jensen Motors delivered additional drawings to Volvo for comments and approval by Tor Berthelius. Similarly, the process of ensuring that spare parts from all suppliers would be available by the autumn when series production would begin. It was certainly a complex task for all the employees involved at AB Volvo and Jensen Motors

In May, it was decided on the production program and execution of the first 50 series-produced cars. All cars were to be left-hand drive, 40 cars with Swedish instrumentation and 10 cars with English. Half of the cars would be equipped with M40 gearbox (4.1:1) and half with the M41 overdrive box (4.56:1). 25 of these cars would be painted red and 25 would be “ivory off white”. Work was also underway to produce the workshop manual and instruction manual, but that work could not be completed until the autumn of 1960 due to the lack and dragging on of the necessary drawing material from Jensen Motors, which was still pointed out from Volvo to Jensen Motors as late as July 1960.

As early as April 1960, the relationship between Jensen and Volvo had deteriorated and Richard Jensen felt compelled to contact Volvo and express his dissatisfaction with the uncompromising attitude of Volvo’s design and construction department towards minor changes to the design that Jensen required in order to achieve cost-effective production of the car. According to Jensen and some of their subcontractors, it was not always easy and possible to mass produce parts with exactly the same appearance and quality as on the handmade prototypes. Jensen proposed changes in the design and specification, but this was not accepted by Volvo. In addition, Jensen had to deal with other changes that occurred, resulting in unbudgeted costs. Jensen expressed its disappointment that when Volvo wanted to make changes to the original design, there was no lack of will to deviate from the prototype. According to Jensen, there was no equality between the parties.

The prototypes from Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors

Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel built three prototypes during 1959 and 1960: P1800-X1 (pencil grey), P1800-X2 (red) and P1800-X3 (red). They had a direct and clear purpose, to provide a necessary bridge in the transition between the three handmade Frua prototypes and the series-produced cars in terms of design and to later serve as display cars and test vehicles for both components and performance.

The first prototype P1800-X1

In the early 1960s, the first and handmade Pressed Steel/Jensen-made prototype was completed. The P1800-X1 was left-hand drive and painted in a pencil-grey hue (Charcoal Grey; I.C.I. number M049-TN16787). On 18 January 1960 the car was completed at the Jensen factory in West Bromwich. Already on January 7, the well-known photographer Lennart Håwi was in England to photograph the P1800-X1 for advertising purposes. The work on the P1800-X1 was carried out under the supervision of Åke Björksund and Gösta Vallin. Gunnar Engellau is said to have personally approved the P1800-X1 when visiting West Bromwich, probably around 25 January.

Among the characteristic features of the P1800-X1 were, among other things, that the gearbox tunnel was different than on the serial cars. The outer bakelite part of the turn signal lever was of a flat model. The car’s threshold strip was of a different design than on the series-produced cars and the car originally had white/beige and black upholstery, probably in vinyl. The floor mat was of a coarser type than on the most series-produced cars of the time, and a carpet with a vinyl edge appears to be in the storage compartment of the rear seat. The rear view mirror had a chromed foot, the gearshift knob was white, and the ashtray was different than on the series cars. As for the instruments, the speedometer was in MPH and even the light controls were English-language. The opening device for the bonnet was of a different model. The P1800-X1 figured a lot in the motor press and was used extensively for test drive and testing at the MIRA track during 1960. Before testing on the MIRA got underway, the P1800-X1 had received a new front axle in early February, the wooden steering wheel replaced with a black plastic steering wheel and equipped with five Goodyear tires. The car had by then only rolled 600 km (350 miles).

The P1800-X1 was used internally by Volvo for the first few years under so-called green sign. The car was approved for the first time in Sweden by inspector Folke Dahlbäck on May 4, 1962, after which it was registered. The car was sold after completing the service and the car’s first owner was Arne Hultberg, who was an engineer at Volvo in Gothenburg. Everything indicates that the sale took place in connection with the sale of the in the salt water-soaked so-called “whiskey cars”. What happened in detail to the car in the first two years between June 1960 and May 1962 is unclear. According to the first registration document, the car was imported to Sweden as “used” and at that time had extensive water damage. These injuries may have been remnants of the moisture damage the car sustained while driving on MIRA.

Much later, namely in 1968, Bo Wallskog in Östersund bought P1800-X1. It was then lacquered red and had beige interiors, lacked the C-pillar emblems and was rusty in both front fenders and sills. The car still retained the following characteristic features of the first two England-built prototypes: The stylized VOLVO lettering on the tailpiece, the different fresh air intakes and the revved-up rear bumpers. Bo Wallskog had the car renovated and repaired all the rust before it was painted white.

Maj Persson bought the P1800-X1 in December 1971 for SEK 3,500 including winter tires, which was a completely normal amount for a used and worn sports car at the time. The car was then still white. The last owner of the car was Kjell Nilsson in Töva outside Sundsvall. He bought the car in 1974 from Johnny Johansson in Matfors. It was white and in drivable, but poor condition and it was bought to be used mainly as a spare parts car. Nilsson owned the car for a couple of years, but due to its poor condition he had it scrapped around 1975–76.

The MIRA tests

The experiments with the Italian-built cars began as early as 1959 when, among other things, a testing program of several months was carried out with the P958-X2 in southern Germany. After the tests with the Italian prototypes, Sture Agård and Rune Fritsby travelled to England in early 1960 to deal with the testing of the first English-built prototype.

Agård and Fritsby took the ferry from Esbjerg to Harwich where they arrived on 26 January 1960 with two Amazons filled with equipment, but at customs there was a halt. The luggage they had with them was considered import, but it was solved by Girling paying £1700 in deposit, otherwise they would not have entered the country. Rune and Sture remember being received by representatives from Girling, because this was during the period when Lockheed and Girling were still competing for Volvo’s orders for disc brakes for the sports car. In the first days, Fritsby and Agård carefully planned the upcoming work. They had meetings with both Girling and Lockheed where they discussed sample setups and similar questions.

When Sture and Rune travelled on their way to Jensen Motors in the Amazon that Sture had with them, they found a suitable hotel in Knowle, the Greswolde Arms Hotel, conveniently located between Jensen and the MIRA Proving Ground (Motor Industry Research Association) in Nuneaton outside Coventry. It was on this test track that the British motor industry did its car tests. It was at the Greswolde Arms Hotel where Sture came to stay for the duration of his country stay, with the exception of a few occasional excursions. In order for Sture to have full access to MIRA, he was employed by Jensen Motors Ltd. A large part of the testing work for the P1800 was carried out at MIRA where all kinds of functional tests were run as well as long-term tests of body strength on MIRA’s special “rough track”.

As in Agård’s case, becoming a Jensen employee turned out to be quite smart. The British car brand Jensen Motors, via its membership in MIRA, had access to their common test track, which the foreign company Volvo did not have. Agård thought that his time at Jensen was both interesting and different. Agård, for example, remembers an incident from the factory when all the workers at Jensen Motors suddenly just disappeared from the workshop just as the engine was about to be assembled in the second English-built prototype. The reason was: “Tea time! Sture also remembers that it rained into Jensen’s factory premises.

By this time, Volvo had let go of some secrecy around the new sports car, therefore it was now possible to use the MIRA track as a test track. In parallel with these tests of the P1800-X1 in England, test engineers from the development laboratory in Sweden, together with the brake suppliers, carried out samples of rebuilt Amazons. Rune Fritsby was responsible group manager for the people from Sweden who were involved in the collaboration with the two intended brake suppliers and Sture, who was appointed project manager for the tests on the P1800-X1. After the introduction at Jensen, Sture was left to carry out the tests on his own without Rune Fritsby’s participation

In February, tests began with the P1800-X1 at the MIRA Proving Ground. The tests were conducted under the direction of Sture Agård and with Gösta Vallin sometimes present. From Pressed Steel, Mr. Finch and Mr. Croxon, among others, participated. The P1800-X1 was also driven by Åke Björksund on a number of occasions both on the MIRA track and on public roads between Droitwich and West Bromwich.

At the MIRA Proving Ground there was, among other things, a shaking track of “Belgian Pavé” which was a standardized imitation of a Belgian cobbled street and which was used for fatigue tests and there were also water trenches. Thanks to Jensen Motors, Agård had access to his own garage by the track, as well as a highly skilled mechanic from Jensen at his disposal. The mechanic named Bob Shiner was the driver when driving tests that required some form of registration, such as brake tests and cooling tests. Bob had previously been a test driver at Ariel Motorcycles. In March, tests began on pavé and corrugated track and then continued into April. Here it was found that in comparison with Amazon and Hillman Minx, the P1800-X1 was significantly more unstable when driving on pavé and significantly more stable when testing on corrugated track. As a driver at the shaker test, Jensen provided two elderly gentlemen, hired from Jensen’s delivery driver service provider, when a new car was going out to dealerships and the like. Agård says that he employed the two hired drivers by driving the car in two shifts, so Sture’s working days became very long.

Sture Agård remembers her England days as difficult but very funny. A fatigue test was done as follows, driving back and forth with the test car for a certain time and at a predetermined speed. The car was driven for three laps after which a lap’s rest and cooling awaited. The car was driven hard and components were continuously replaced. “The shock absorbers got very hot at the shake tests, we drove through a large water trench for water to splash up on the shock absorbers and cool them down. During this exercise, both water got onto the floor and exhaust gases were drawn into the passenger compartment through the unsealed joints in the floor and torpedo, says Agård. The tests were carefully recorded and all modifications carried out on the car were continuously noted in protocols in parallel with the current miles that the car had gone on each occasion. Everything from changing controls, gaskets and thermostat to car wash was noted.

Engine designer Per Gillbrand travelled several times with engine parts for MIRA. During the tests, among other things, it was found that the attachment of oil coolers and carburetors had to be improved, it also turned out that the engine suspensions took a lot of beatings. According to Rune Fritsby, the Laycock de Normanville overdrive gearbox did not quite live up to Volvo’s quality standards. They also tested Lucas, which was Jensen Motors’ regular supplier of motor electrical components, but then switched to Bosch instead. Finally, Girling and Lockheed would show off their findings regarding the disc brake system. Volvo finally chose Girling’s solution and in doing so, the P1800 was probably the first series-produced standard car to be equipped with working self-adjusting disc brakes on the front wheels.

The purpose of the stay at MIRA was to drive the car in extreme conditions and note in detail what was broken. On April 8, 1960, a reconciliation meeting was held at Jensen Motors where representatives from Volvo, Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel met to discuss emerging deficiencies. Mr. P.M. Finch of Pressed Steel made a list of 21 items where some of them were more serious than the others. Among other things, a number of cracks had been noted both in the chassis and in the frame structure adjacent to the front axle and around the radiator. The position of the door changed and the tires did not measure up. The shock absorbers took a lot of beating during the test period. A lot of energy was transferred from their mounts to the body and it was discovered that the sports car’s attachments for the rear shock absorbers over the rear axle were far too weak and the sheet metal cracked or deformed. This was very serious and the forces had to be spread better. Many of the shortcomings of the chassis were solved by the fact that extra reinforcements were welded there. Front axle with suspension device was sent to Pressed Steel, which was tasked with reinforcing these parts for future series production. It was urgent because both Volvo, Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors wanted production to start as soon as possible and such late changes were not welcome.

The P1800-X1 was subsequently sent back to Pressed Steel where the necessary additions were carried out and in early May the pavé tests at MIRA resumed to end on 9 May with an inspection after which the test equipment was assembled and the P1800-X1 was returned to Pressed Steel. In a May 18 protocol, the recently completed 1,000-mile pavé test of the P1800-X1 was summarized. Here it appeared that a number of cracks had occurred in various welding joints, the floor, the rear axle, around the radiator, on the front fender and at the opening of the bonnet to the windshield. In addition, the mounting device for the gearbox had failed. At the end of May, the P1800-X1 was again picked up at Pressed Steel and the rear axle, front suspension, steering joint, as well as the adjusted front axle and gearbox assembly were changed. Finally, a speedometer of the original design was reassembled.

The second prototype P1800-X2

The second car that Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors built was a red left-hand drive car with white and black interior that was used as a test and display car by Volvo in Sweden. Leif Olsson remembers that the P1800-X2 reached Volvo control in early March 1960 and had previously been finally inspected by Jensen’s staff. Volvo’s inspection took several hours to carry out and when it was completed, lots of remarks had been noted, which was a disappointing result for Jensen. Olsson remembers that Jensen’s final adjuster was in a minor state of shock, but Volvo’s controllers were helpful throughout.

Åke Björksund says that the P1800-X2 was completed in March 1960 and immediately after its completion it was transported to Sweden. Gösta Wallin and Åke Björksund were commissioned to drive the car down from Birmingham to Southend on Sea outside London. Here, too, there was a lot of time pressure and the departure from Birmingham was slightly delayed at 2.30 pm after dinner on 14 March. The car, which went with Pressed Steel’s registration plates “45AEA”, was steered by Vallin and Björksund was a co-driver in the rain and fog. They had an Amazon as a companion car driven by a colleague at Volvo named Bjurö and they arrived at the airport in Southend at midnight. The following morning, March 15 at 09:00, the P1800-X2 was flown to Sweden with a specially chartered transport aircraft, an old military aircraft. The airline was called Channel Air Bridge and they also flew other routes across the channel to Ostend in Belgium, which was a common route for Volvo staff who would travel home with their car from England to Sweden. Sven-Olof Andersson made that particular trip several times.

This was the P1800-X2, which was the very first Jensen-built prototype to arrive in Gothenburg when it landed on Swedish soil in late March 1960 and testing work began. It turned out, among other things, that the strength tests at MIRA and the improvements made had paid good dividends, since no problems in the body showed up during the intensive long-term test on the Swedish country roads. Other issues that were specially processed were material properties, engine cooling, heat conduction, disc brakes, etc. The disc brakes were specially studied with regard to the influence of dust and dirt from dirt roads and it became necessary to introduce special mudguards for the brakes in order for the service life of the brake pads to be satisfactory.

P1800-X2 was completed on March 24, 1960 for registration in Sweden carried out by Carl L. Engström and it was first registered in Sweden on April 1. Shortly after arriving in Sweden, Gunnar Engellau test-drove the car for a few hours over a weekend when he made several notes that were summarized and conveyed to his responsible Volvo directors and engineers, Tord Lidmalm, Tor Berthelius, Gerhard Salinger, Thorsten Laurent and Gösta Vallin. 31 different points were noted by Engellau and in summary he pointed out that the driving characteristics were very good, that the car at least had “emotionally good acceleration” and, above all, the brakes seemed to be excellent. The biggest negative remark from Engellau was that when switching from the 2nd to the 3rd and from the 3rd to the 4th, there was a very strong blow in the car when the clutch was released, which he asked his colleagues to fix immediately. The second major remark was concerning the wind blowing with open windows inside the passenger compartment that needed to be investigated. Engellau had been driving with the side window open and a couple of different passengers and all complained that it was impossible to sit on the passenger seat with the window pulled down.

Svante Simonsson also did a short test drive during an afternoon in April 1960. He had both positive and negative feedback to convey. Among the positive qualities, he highlighted; excellent acceleration and brakes, road holding, steering and driving position. Simonsson found that the footrest on the left was a good finesse and that the look from the front and from the side was appealing, but that from behind he associates the car with a “duck tail”. Among the negative reviews, the following dominated; loud transmission, hard-to-reach hood lock, the function of the body as resonance box (“chirping and rattling from the rear carriage is very well heard”), the absence of interior lighting and signalling device with high beam, indication lights for turn signals invisible to the driver, useless ashtray, whining, howling and annoying wind noise in the car in particular from the ventilation windows (which, incidentally, could not be opened to ordinary people), sluggish window lifts, internal ceiling too low and that the entire interior seemed cheap “not to say dilettante”. Those were clear and rather harsh words from one of Volvo’s top executives. The car was at Volvo in Gothenburg in the spring of 1960 and the deficiencies noted were processed by Tor Berthelius and then passed on to England in April. During July 1960, Volvo colleagues in Sweden expressed some additional views on the P1800-X2, which Gösta Vallin passed on to Jensen Motors. This concerned, among other things, the design of cabling into the passenger compartment.

The P1800-X2 often appeared in the motor press and was shown in various contexts, but in the spring of 1962 Volvo no longer had any use for the car and it was sold to a Volvo employee, Gösta Stegborn, who owned it for a couple of years. One of the later owners of the car, Kristian Hallor, says that he got a tip about the car from a friend and traveled up to Umeå from Stockholm to buy it. It had then been on the workshop recently after a crash damage to the rear piece. The car was then freshly painted in cherry red color with black interior, yet some rust damage remained and there was a need for welding on it. Kristian Hallor later installederted a tuned B20 engine in the P1800-X2. The B20 engine was equipped with, among other things, time-typical tuning in the form of a factory-tuned cylinder head, a Rambler four-port carburetor with intake manifold, “Nisse Hedlund 49 ” camshaft, “slimmed-down flywheel”, “fan clutch” and wide rims. The engine’s power was estimated at about 160 hp, and Hallor thus managed to achieve what Arthur Wessblad called for in connection with his test drive of the P1800-X2 in March 1960 to achieve sufficient racing performance, i.e. a power factor of about 7.5 kg.

While in Stockholm, the P1800-X2 was subjected to more burglaries and Kristian says that he equipped the car with a playing horn that he also very cleverly connected so that it also served as a theft alarm. Two large mousetraps were painted black and mounted between the ventilation window and the inner opening handle to scare undesirable guests trying to break in. The car was sold on to new owners in Malmö and later the traffic police carried out a flying inspection of the car on November 20, 1973, where a number of deficiencies were found, including splash guards, lanterns and parking and service brakes. When the police carried out another inspection of the car on 10 March 1974, they found such extensive deficiencies that it was decided that it was in too poor a condition and issued a driving ban. It was scrapped in May 1974 at Harrys Bilskrot in Malmö, a scrap yard that still exists today. At the scrapyard, staff, who also worked there in 1974, state that over the years more rusty Volvo P1800 have been scrapped. Today, there is no longer any trace left of any P1800 on the scrapyard.

Detailed test drive of the P1800-X2

On March 28 1960, the red P1800-X2 prototype was tested in Sweden by Arthur Wessblad, head of Volvo’s motor sport department and a rally driver.

Distance: 185 km (115 miles)

Conditions: Varying road surfaces, dry road.

Driving position: Excellent, with a very good left foot support.

Steering wheel: Good looking and nice to hold. The wood may however cause splinters and injure the driver in a crash.

Glove compartment: Needs a lid, otherwise the contents may fall out under full acceleration.

Pedals: Well positioned.

Light switch: Well positioned.

Ventilation: Rear opening quarter lights wanted, or some other solution for the evacuation of used air (preferably not through leaking doors or windows).

Wind noise: At speeds exceeding 120-130 kph (75-80 mph) a lot of wind noise was noticed inside the car. Must be reduced to the highest possible degree.

Safety belts: The middle anchor point on the tunnel must be adapted to suit the forces of the movement of the belt (risk for handle damage).

Instrumentation: Speedometer, fuel gauge, clock, water temperature gauge, oil temperature gauge, revcounter (must be red marked) are all ok. The oil pressure is obscured by the steering wheel and the driver’s right hand and should change position with the clock. The lighting of all instruments is reflected in the windscreen during night driving. Must be sealed off.

Wipers: Speed and blades are ok. The lower left section of the windscreen is not reached by the wipers which is not acceptable.

Control lamps: Ignition, indicators: the position of these is impractical and obscured by the steering wheel. They should have a central location in front of the driver like the rest of the instruments.

Cigar lighter: Must have a protective sleeve like the one on the Amazon

Ashtray: Could also be positioned on the centre tunnel, behind the gear lever.

Heater controls: Instructions for their adjustment are missing.

Horn: The control well positioned but a little too sensitive and may cause some involuntary hooting. Can be replaced with a lever which must be pressed or which can only be used by a movement.

Seats: OK

Armrest: OK

Doors: OK (a little sluggish on the prototype)

Rear view mirror: Size and position ok considering the need for forward and rear vision.

Bonnet: The catch for the opening should, if possible, be located on the driver’s side.

Spark plug connections: The fitting of the cables should be replaced with the type that connects directly on to the spark plug threading, thereby minimizing the risk of disconnected cables.

Brakes: Brake distribution, pedal force needed and all other properties are all satisfactory.

Transmission: Well-laid out ratios between gears and a well-positioned gear lever. Third gear sometimes needs too much force to be engaged. Reverse gear awkward to engage due to the lift release mechanism (when reversing, the gear also kicked out at several occasions). Noise level in second and third too high.

Engine: Torque good. Acceleration adequate, but not more. Noise level at engine speeds above 4,000-5,000 rpm annoying (the engine is probably not adjusted correctly, pinking at loads, backfiring tendencies). An engine temperature of 90°C on 28/3 is probably too high considering the future use in warmer climates.

Suspension and steering: OK – a change of tyres would probably improve the car’s behaviour. The car must be tested with so-called belt tyres. When driving over bumpy roads the steering wheel rattled, A steering damper?

Motorsport performance: With a weight to power ratio of appr 11 kg/hp the car is fairly limited. Many competitors have a much more favourable ratio. In order to be successful the car needs a ratio of around 5-7 kg/hp.

The third prototype-X3

The third car that Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors built was a red left-hand drive car with white and black interior that was used as a test and display car. By May 1960, work on the car had begun and at the same time the stock of details for the P1800-X3 that had been built up at Jensen Motors in West Bromwich was reviewed. During the inventory, Sture Agård was able to establish that due to the many changes that had to be made to the P1800-X1, there were no components to be able to complete the P1800-X3. This car was the first P1800 with pressed sheet metal parts from Pressed Steel and was partially welded together by hand. An internal letter from E.W. Neale at Jensen Motors stated that the goal was for the P1800-X3 to be ready for inspection and approval by Volvo’s directors on June 24, but that schedule did not hold up. It is also clear from the letter that it was of the utmost importance to complete the car as soon as possible in order to complete all specifications and assembly devices, to approve all components from Pressed Steel and other external components, and to be able to complete all texts for service manuals, sketches and photographs. The car wasn’t ready until after the summer. It was intended for advertising photography and to be part of Volvo’s test program in Sweden. The P1800-X3 received, among other things, a different type of fresh air intake, probably the same as the production version. The car then appeared in Volvo’s marketing materials and advertising brochures during 1960 and 1961.

It was the red P1800-X3 used in September 1960 in the photo shoot for the first sales brochure carried out by Georg Oddner at various locations in England, including at an estate. In early October 1960, the car was still in England and a variety of modifications were carried out at Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors. Among other things, controls, handles, window grooves, sealing strips, front seats, exhaust system, sun visor and steering wheel were changed to production design. Likewise, the accelerator pedal and horn controls were adjusted, while rubber mats to the front floors were fitted in. The P1800-X3 was delivered on 24 January 1961 (TSU number 329–1146) to Volvo’s laboratory, under the authority of Åke Larborn, for long-term testing. During February 1961, the P1800-X3 was in Sweden under a so-called green license plate and it is the last trace of this car. According to information from staff at Volvo’s engine laboratory, the car is said to have been badly damaged in a fire that occurred during tests.

The first right-hand drive prototype P1800_X1 H

Åke Björksund says that during the time he worked at Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel, he was not involved in any development of the right-hand drive P1800. Björksund comments that since the Amazon was already available in a right-hand drive version, there were probably no extensive changes that would be required to go from left- to right-hand drive cars. Details and timing for a right-hand drive variant of the P1800 had already been discussed in the initial phase of the sportscar project and Director Engellau finally decided on November 21, 1959 that the right-hand drive P1800 should be produced. Later in May 1960, Volvo commissioned Jensen Motors to design and develop tools and materials for a right-hand drive version of the P1800, which was primarily developed for the English and Australian markets.

It is not entirely clear when the first right-hand drive prototype began to be produced, but from the correspondence between Volvo, Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors, it appears that work on constructing a right-hand drive variant began in earnest at the end of November 1960 when Volvo and Pressed Steel were formally commissioned to develop a right-hand drive P1800 with the number “X-7”. Volvo’s plan in January 1961, was for a right-hand drive prototype to be completed by April 1, 1961, and four more pre-production cars by June 30, 1961, with series production to begin on September 1, 1961. However, this came to be displaced about seven months. The first body with the number H001001 for the first right-hand drive prototype was delivered to Jensen Motors in January 1961 and the subsequent four pre-production bodies were delivered during the month of May.

The first prototype car P1800-X1H was probably completed in March 1961, after which the four pre-production cars were manufactured immediately and completed in June. Volvo subsequently ordered 496 bodies for right-hand drive cars from Pressed Steel. At the same time, Volvo was arguing with Jensen Motors about an order for the assembly of an equal number of cars, but the order was returned to Volvo on at least two occasions and the process was marred by irritation regarding constant delays, which Volvo perceived Jensen Motors to cause. Opinions were divided as to whether the right-hand drive variant of the P1800 really formed part of the original contract for the P1800 and that these conditions, including pricing, would also govern the development of the right-hand drive car. In September 1961, however, Volvo placed the formal order for 496 right-hand drive cars, which formed part of the original order for 10000 sports cars that Volvo had ordered from Jensen Motors on August 22, 1960. On September 11, 1961, the parties agreed on the details of the pricing of the right-hand drive cars, and at last production could begin. The official series production of right-hand drive complete cars was initially planned to begin in June 1961, but it took until the autumn of 1961 for production to start in earnest. The first cars officially began production from chassis number 3001 and were completed in early February 1962.

The P1800-X1 H was white and originally had red interior. The body number is H001001 which means that it is the very first right-hand drive series-produced body and also the steering box’s date stamp (7/60) and the date marking on the car’s windows tell us that it is an early car and prove this. Other details that tell us that it is an early car are the bolts to the fan cover that are narrow, metal staples for the cable harness that is pop-riveted and not welded as on later cars, that the sign with the car’s body number is down on the frame leg, that the car has rounded the roof at the rear edge and that the ventilation window has screwed hinges. However, the car is not based on an amazon chassis, but on a series-produced floor from Pressed Steel. The car was probably retained in England as “equal” for right-hand drive car until production began in the late autumn of 1961. Then it was sent home to Sweden and registered in January 1962 with the clothing company Oscar Jacobsson in Borås. The car was type-approved in Sweden on January 25, 1962 by N.-O. Johansson when the first Swedish registration certificate was issued. In 1962, the car had a 100 hp engine and radial tires. Since Sweden had left-hand traffic until 1967, this car was a perfect fit in Swedish traffic.

It could well be the P1800-X1 H that is visible in photographs taken at the Earls Court Motor Show in London in October 1961, as that car has details that align well with early series-produced cars such as the seat belts fastened below the B-pillar. In the British motor press there was a white P1800 in the early 60s with registration number “X1800”. As mentioned, Volvo did not start manufacturing the right-hand drive P1800 in official series production until from chassis number 3001, but there are still some known cars with lower chassis numbers that were demonstrably right-hand drive from the beginning, e.g. chassis number 599, which now runs in Sweden and is converted to left-hand drive. The oldest rolling series-produced right-hand drive P1800 today has chassis number 3004, is now available in Sweden and has registration number BGH615.

The P1800-X1H entered service in Sweden in early 1962 and has since had many different owners over the years. Since the mid-1970s, the car has been decommissioned for renovation. The current owner found it in a very poor condition standing outside the banknote printing house in Tumba. To find the owner of the car, he had to knock on doors in the area. At that time, a renovation had already begun, among other things, with the help of coffee can metal sheets that had been riveted and covered with large amounts of undercarriage pulp. There is now a great deal of work to be done to get the car back on the road. The P1800-X1H is unique in the sense that it is the only known remaining Jensen-built P1800 prototype.

The final assembly of the P1800 is started

The goal was for the serial production of the P1800 to be up and running during September/October 1960, but in the spring of 1960 Jensen Motors was still building on the extension of the factory to cope with the work on the assembly. Volvo’s management could already fear that the project would suffer even more delays. During 1959 and 1960, many long letters between Volvo and the General Customs Board were devoted to jointly interpreting and understanding the complications regarding various customs issues that would apply to the car as it was assembled in England and “imported” to Sweden. At the prototype stage by mid-1960, the type designation of the sports car was “P1802” as evidenced by a document from Thorsten Laurent. In the document, Laurent referred to a decision of the General Customs Board which claimed that, in order not to conflict with the law on incorrect designation of origin of import goods, Volvo was obliged to provide the chassis number plate with the additional text “Assembled in England (assembled in England) by Jensen Motors Ltd.”. It then became Åke Björksund’s task to design the chassis number plate.

Preparation at Jensen Motors