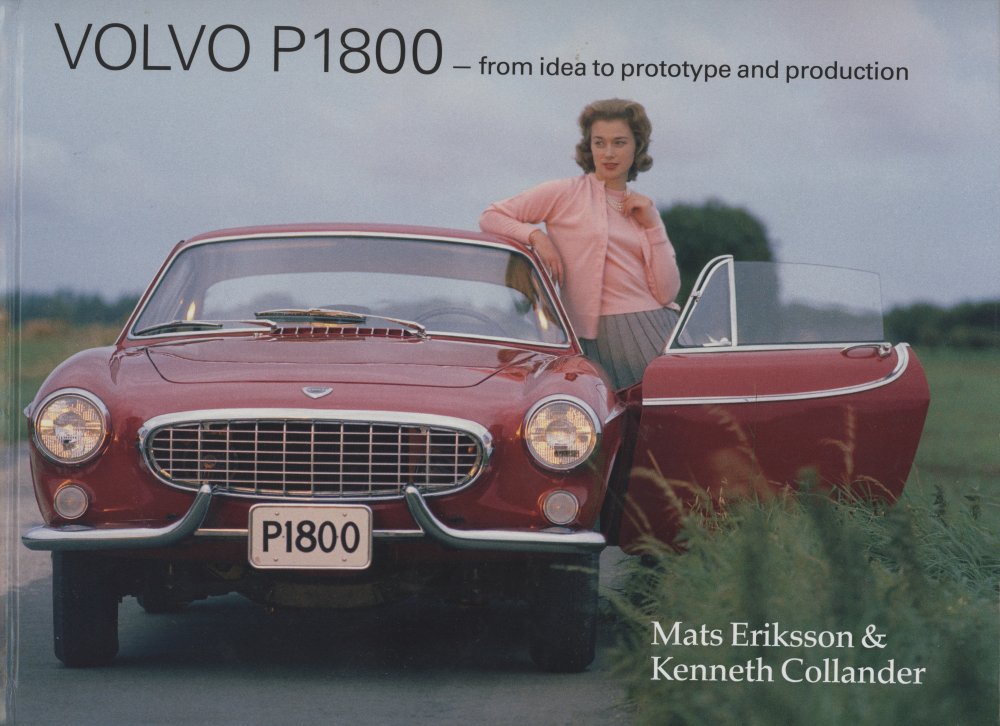

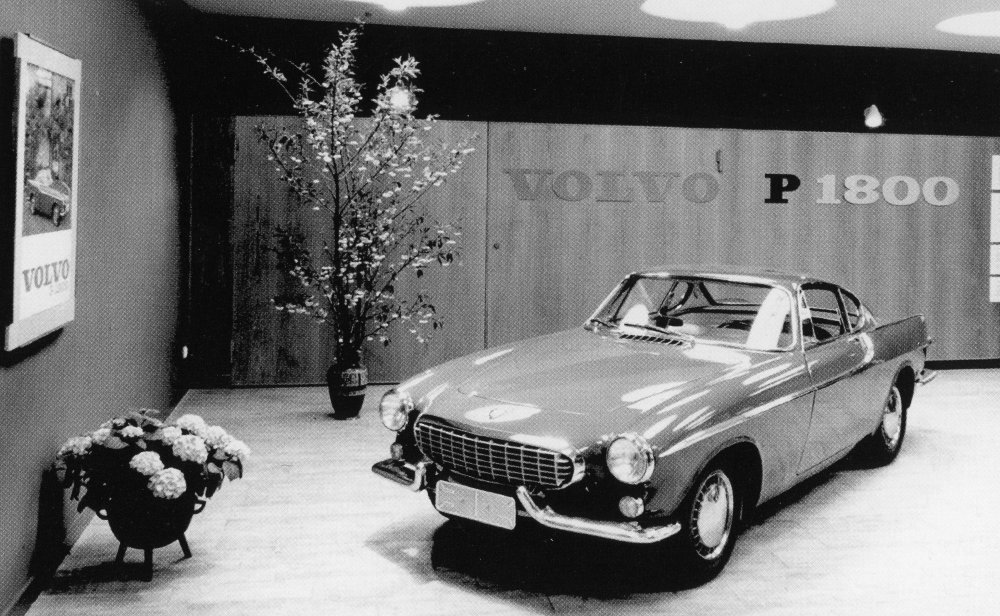

The car on display on international motor shows

Suppliers of part and components

Organizing the components and parts for the P1800

Transporting the P1800 from Britain

Quality problems during the early production

Problems with bodies and supplier components

The crisis deepens

Faults identified by Volvo’s delivery inspections

The Very first production car

Major problems on early cars

The Volvo P1800 is shown to the Public and the press

A technical presentation

Chassis and body

The delivery situation during the spring of 1961

In the Volvo dealer showroom 1961

The car on display on international motor shows

In October 1960, the launch plan for the new sports car had been decided to be one of a simultaneous launch – same time on the same day – in five different places: Gothenburg, Frankfurt am Main, Paris, London and Geneva. There was also to be additional launches at a later point in Los Angeles, New York, Buenos Aires and Johannesburg. Volvo planned to introduce the car in January and this was decided because January was considered to be a month of generally weak sales for new cars in many markets and therefore a boost could be useful in order to get people into the showrooms. The launch in the five cities in the same time demanded the presence of five top men from the Volvo management. The selected directors for the job were Gunnar Engellau, Svante Simonsson, Per Ekström, Per Eriksson and Ulf Wollin. The plan was also to throw in a number of expert spokesmen. The people who were chosen for the Gothenburg launch were Lidmalm, Bertelius, Blenner and Mankert while Vallin, Sharpin, Singer and Ericsson would make up the London team.

The setup was supposed to be carried out like this: After the introductory presentation, a test drive session started and on return, the guests were given time with the experts to whom they they could direct questions and points of view, press conference style. Comprehensive presentation material was produced for the purpose. After these presentations had been carried out, Volvo was planning to continue at dealer level. Constant delays and lack of cars for these presentations led to the fact that this could never be carried through. The presentation on the Continent took place at a much later stage than those made in the Scandinavian countries.

The production cars now started to be delivered but Volvo still used the prototypes for internal tests and marketing purposes. In the late winter of 1961, the Italian were still in use at Volvo. The Car drawings office had the P958-X1, the P958-X was earmarked already for a future Volvo museum and the P958-X3 was in the hands of US Volvo dealers. The British P1800-X1 was used by Public Relations and the P1800-X2 and P1800-X3 by the Laboratory

The British Lex group was a large group of automotive market companies and the owner of Brooklands of Bond street. Here, Charles Singer was director and general manager. Singer had in late 1958 closed a deal with Volvo about the import and sales of Volvo cars in Britain and he was to play a major role of the marketing of Volvo P1800. He and Helge Castell were discussing which cars to use on the Volvo stand at the Earl Court Motor Show in 1961, a show of major importance in those days. Singer was most eager to make sure that the Volvos on display must be immaculate, more than perfect. As the story goes, it was actually Charles Singer who saw to it that the P1800 came to be the car used by Simon Templer in “The Saint” television series. Originally it was the intention of the producers that Roger More was to drive an Aston Martin, which Lex Group could supply, but later changed to the new Jaguar E-type. In the end, however, it came to be Volvo P1800 and the rest is automotive history.

Poster from International Motor Show. Eeuwfeestpaleis du Centenaire, in Brussels, Belgium, January 11-22. 1961 |  The International Motor Show Geneva, Switzerland 16-26 of March 1961. |

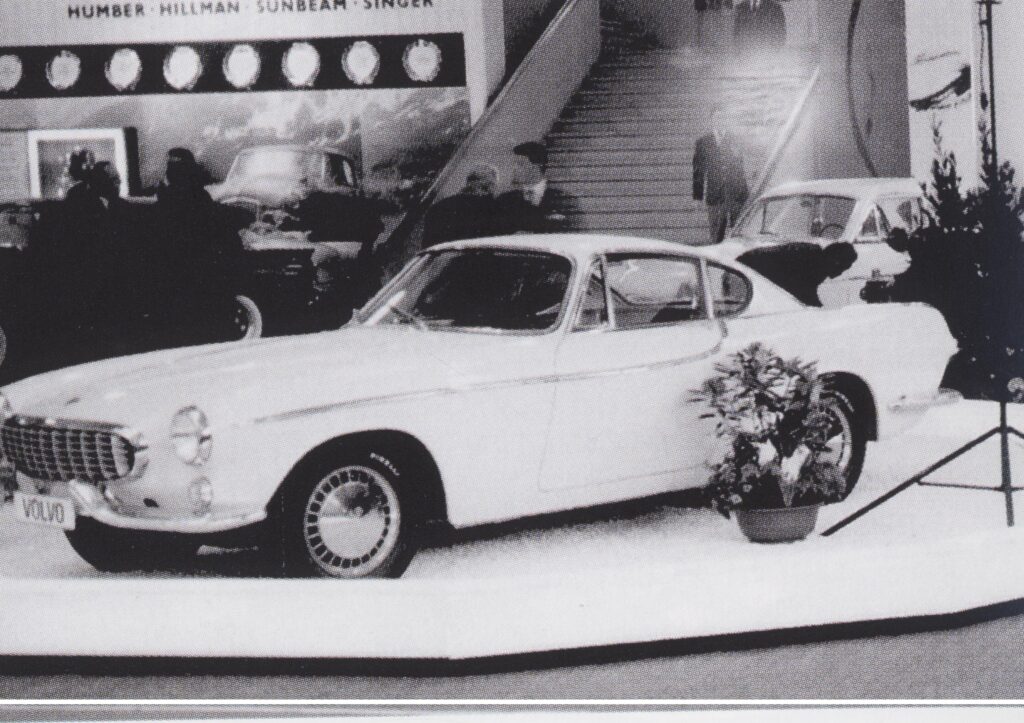

The poster from the International Autombile Show, New York, 1-9 April 1961. The car showed there was the white chassis 6 |  The International Motor Show Geneva, Switzerland 16-26 of March 1961. The car on show is an early production car in white |

The new Volvo was shown at a number of international motor shows all aver the world, among them shows were these photos were taken. The P958 came back to its native Turin and was on exhibitionat the Palazzo Esposizioni al Valentino in November 1960, P1800 chassis number 6 in white was used in April and May 1961, the red number 18 was shown in Casablanca Morocco

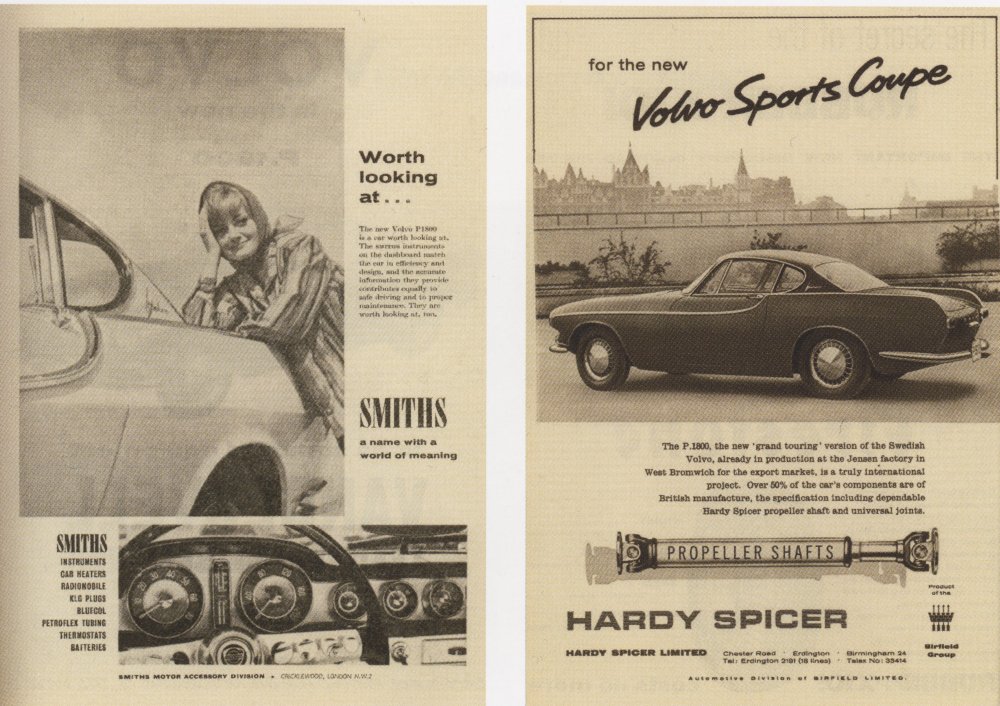

Suppliers of parts and components

Already in the beginning of 1959, Volvo and Jensen started to plan the handling of spare parts for the future. According to the deal, all necessary base work for the spare part specifications was to be made ready by Jensen by September 1960. Many of the components for the Jensen-built cars came from British suppliers. Jensen did not make any parts or components of their own but were responsible for what they purchased from outside. Volvo had no right to buy anything from these suppliers, according to the contract. The relation between the two companies had already at this point started to become strained and during the spring of 1961, they deteriorated even more. The reason was the Jensen inability, or lack of ability to arrange for the Volvo spare parts. Volvo therefore started to scan the market in order to investigate if they could purchase directly from from some of the companies, avoiding Jensen altogether. Such companies were Lucas, Wilmot Breeden, and Smiths. After heated discussions, Jensen consented to a temporary solution, allowing Volvo to carry on with direct purchasing from these companies.

After pressure from Volvo , it became apparent that Jensen really tried hard to correct the situation, on the other hand, blamed Volvo for obstructing the process of approving components and parts, causing unnecessary delays. They thought that the Volvo inspectors working at Jensen were too strict and took their task too seriously, causing the scrapping of too many parts. Jensen was also of the opinion that their suppliers were afraid to produce in large enough numbers because of the fear of having to scrap too much and therefore made just enough parts to cover the need for the series production.

Volvo had high demands for fit, finish and quality and several of the suppliers could simply not meet these demands. One such supplier was Sankey. They had just carried out the modification of the rear bumper in order to make the production easier. When Volvo refused to do the same to the front bumpers, this was not accepted by Sankey and the cooperation was only continued on the the grounds that Volvo could simply not find a replacement supplier.

Triplex had made and delivered laminated glass for the rear window according to Volvo’s requirements, something which irritated Jensen. Later, Volvo changed their minds and went for hardened glass instead on Jensen’s suggestion. This however resulted in Jensen suddenly having supply of useless rear windows and had to use a glass which was considerably more expensive. Jensen’s demand for compensation was met by Volvo stating that Volvo had supplied the correct specification but that had not been followed by either Jensen or suppliers.

| Area | Responsible/Supplier | Country |

| Concept | Gunnar Engellau | Sweden |

| Technical design drawings | AB Volvo | Sweden |

| Technical design drawings | Jensen Motors Ltd | Great Britain (England) |

| Technical design drawings | Pressed Steel Co. Ltd | Great Britain (Scotland) |

| Planning of the sports car project at the prototype stage | Helmer Petterson | Sweden |

| Exterior and interior design | Pelle Petterson | Sweden/Italy |

| Prototypes, three LHD | Carrozziera Pietro Frua | Italy |

| Prototypes, three LHD and one RHD | Jensen Motors Ltd Pressed Steel Co. Ltd | Great Britain Great Britain |

| Engine, design & engineering | AB Volvo | Sweden |

| Transmission design & engineering | AB Volvo | Sweden |

| Body incl front member | Pressed Steel Co. Ltd | Great Britain |

| Final assembly | Jensen Motors Ltd | Great Britain |

| Shock absorbers | Delco-Gas Freon | USA |

| Jack | Metalifature Ltd | Great Britain |

| Radiator | Willenhall Motor Radiator Co. Ltd | Great Britain |

| Rear axle | Hardy Spicer & co | USA |

| Prop shaft and joints | Hardy Spicer & co | USA |

| Cable harness, switches | Joseph Lucas | Great Britain |

| Lamps, battery | Joseph Lucas | Great Britain |

| Instrumentation | Smiths Motors Accessory Division | Great Britain |

| Horn | Robert Bosch | Germany |

| Seats | Dunlopillo Cushions | Great Britain |

| Chrome strips | Smiths | Great Britain |

| Radiator grille | Joseph Fray Ltd | Great Britain |

| Starter motor, dynamo, ignition system | Robert Bosch | Germany |

| Chromed details | Joseph Lucas/Joseph Fray Ltd | Great Britain |

| Brakes | Girling | Great Britain |

| Brake discs | Pianoforte Suppliers Ltd | Great Britain |

| Clutch | Borg & Beck | Great Britain |

| Vacuum booster | Girling | Great Britain |

| Tyres | Pirelli | Italy |

| Wheels 4 1/2 x 15′ | J Sankey & Sons Ltd | Great Britain |

| Hub Caps | Cornercroft Limited | Great Britain |

| Exhaust sytem | Servais | Great Britain |

| Carburettors | Skinner Union (SU) | Great Britain |

| Pistons | Mahle | Germany |

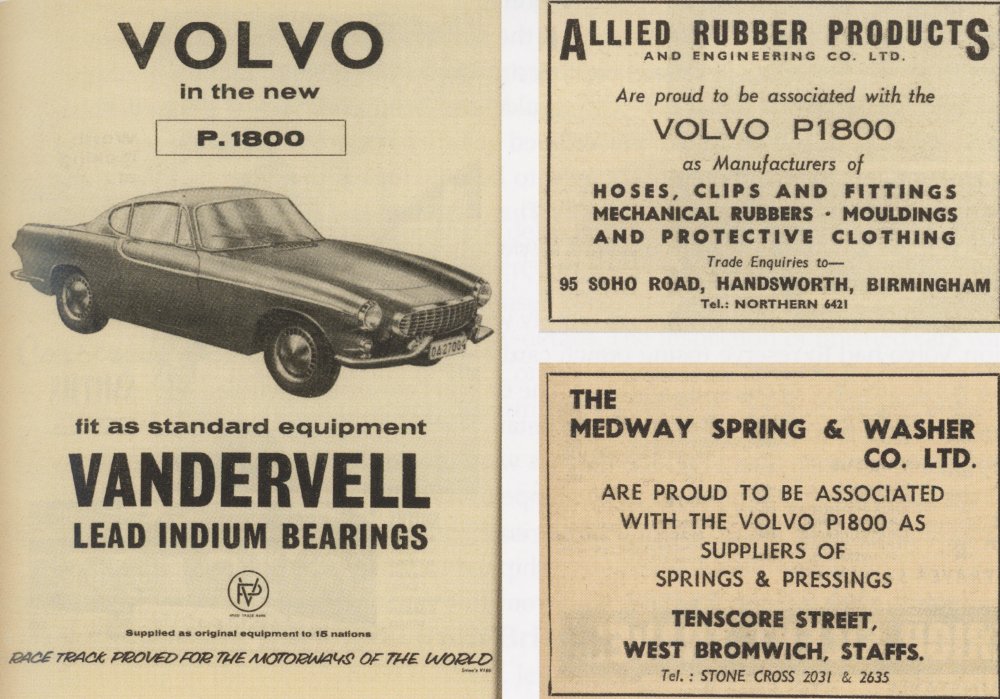

| Engine bearings | Vandervell | Great Britain |

| Overdrive | Laycock De Normanville | Great Britain |

| Springs, bolts, nuts, washers | The Medoway Spring & Washer Co. Ltd | Great Britain |

| Rubber seals, hoses, protective covers, clips and rubber details | Allied Rubber Products and Engineering Co. Ltd | Great Britain |

| Suspension components chassis | Allied Rubber Products and Engineering Co. Ltd | Great Britain |

| Plastic plugs for floor and sills | C.O.H Bains Limited | Great Britain |

| Glass | Triplex | Great Britain |

| Windscreen | Worcester Windshields Co. Ltd | Great Britain |

| Steering gear | ZF | Germany |

| Dashboard, door panels, panels and armrests | Pressed Steel Co. Ltd | Great Britain |

| Steering wheel | Steering wheels, Birmingham | Great Britain |

| Wooden rim steering wheel | Clifford covering | Great Britain |

| Bumpers | J Sankey & Sons Ltd | Great Britain |

| Insulating cardboard | Luxan Ltd. | Great Britain |

| Locks and keys for doors, boot and fuel filler cap | Wilmot Breeden | Great Britain |

| Body paint | ICI | Great Britain |

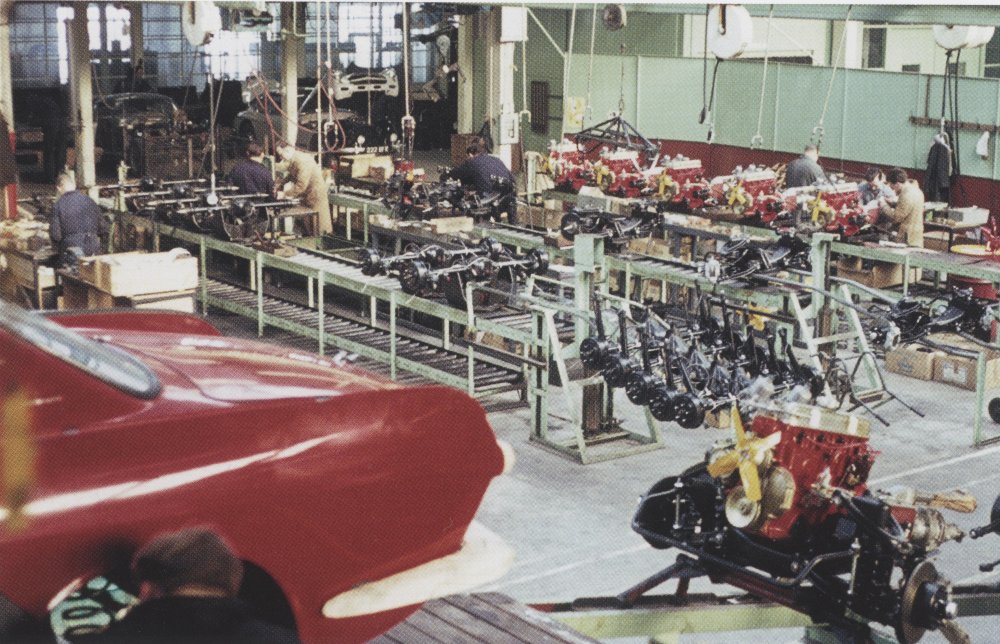

Organizing the components and parts for the P1800

Organizing the logistics surrounding the British operation was not an easy task. In a story from rom Volvo personnel magazine “The Air cleaner” from 1962, Lennart Lindgren, head of Volvo’s central register, described the way P1800 details were packed and shipped. He calls the car the little sister in the Volvo family and gives an account on what it is like to produce a car in a foreign country. This was new to Volvo at the time even if some experience had been gained by the CKD operations (Completely Knocked Down) i.e a car kit form for assembly somewhere else. Instead of having Volvo getting all the pieces together in Gothenburg and build the car there to their usual standard, it was now a matter of creating an efficient logistic system.

It was very much a matter of balancing the different batches of components making sure that the supply to Jensen was kept at the right level, with neither a shortage nor excess of parts. Volvo’s central register was responsible for the packing done in the right way at the right time, and how problems that occured were solved. The P1800 details were split into four groups:

1 The X-details (mainly chassis details)

These parts were purchased and delivered to Gothenburg from where they were shipped to Britain. According to the plan, Jensen was going to produce between 100 and 150 cars per week. The buffer stock of parts at Jensen was design to cover four weeks of production, and taking a transport time across the North sea of two weeks in consideration, the batches had to be some 900 kits ahead of the production. If all X-details had been packed in batches of one week of production, some 22,000 items per year would have been packed and shipped. Volvo received most details packed in pre-ordered quantities or delivered by sack from their suppliers. It was therefore though to be only logical that Volvo delivered the parts in batches using the same quantity. Thanks to this, the annual packing of items was a mere 2,000. The warehouse had a special space for P1800 parts and this was where the packing took place.

Having decided that the Jensen supply was to be limited to four weeks production, Volvo had to reserve (using punch cards) the parts and quantities needed four weeks in advance of the shipping date.The delivery controllers worked according to a detailed delivery plan for every single detail. The shipping department booked the necessary space on board and the batches were invoiced pro forma to Jensen. Most of the cars that they built were to be shipped out of Britain and the parts for these cars were stored by Jensen duty free while customs duty was paid for parts that were used for British cars. As the items were shipped to Jensen, they were registered on cards in the Volvo central register and from this card the needs for every week of production was taken and noted

2 The N-details (mainly nuts, bolts and washers)

These were taken out of the central register and shipped in the same way as the X-details but Jensen stock of N-details was not noted in the Volvo Central register.

3 The V-details (mainly chassis details)

For parts bought by Volvo in Britain for delivery to Jensen, the Volvo Central register received report when they were delivered to the Volvo warehouse a Jensen. They were subsequently registered on the Jensen cards in the Volvo Central register and were invoiced in the same was as the X-details. The inspection of finished cars was carried out by three members of the Control department, assisted by one person from the Design and Engineering department.

4 The J-details (mainly body details)

These were delivered and made by Jensen Motors Ltd.

Transporting the P1800 from Britain

According to the Volvo/Jensen contract , Jensen Motors Ltd was responsible for the transportation of the complete cars from the West Bromwich factory to Liverpool for subsequent shipping. This trip was undertaken by trucks and it was Volvo’s Lars Grapengieser who together with a British transport company handled this.

It was Tord Lidmalm who decided which car was going where at the beginning. On April 24 1961 it was decided that the first 200 cars would be shipped to Volvo in Gothenburg for inspection and quality control before being delivered to dealers. Starting with chassis number 201, jensen was going to ship the cars directly toe the respective market.

Two years passed from the first information about the new Volvo sports car was released until the the first production cars were delivered to the dealers and put on display in the showrooms. In the USA, there were customers patiently waiting for their new car for which they had paid a deposit already a year earlier, but maybe without their initial enthusiasm. First of all the Swedish need was going to be met according to Simonsson.

Quality problems during the early production

1961 started the same way as 1960 had ended, with problems and delays. During the initial stages of the series-production, the problems were frequent. By the end of March 1961, not a single car had been passed by the Volvo Quality control in Gothenburg. All cars had so far failed the inspection, and been the subject of subsequent corrections. This continued until May, preceded by a four weeks production stop at Jensen due to the quality of bodies, Volvo’s lack of ability to approve the cars and their constant demands for modifications. During September and October, another stop was caused by the number of cars sitting idle on the assembly line, waiting for parts.

In the early days of 1961, Richard Jensen bitterly complained about the uncompromising attitude of the Volvo inspectors whom he regarded as risking the entire project and just made all involved feel bad. He went so far as to, at a later stage, demand that one of the Volvo inspectors should leave Jensen and never return.During the period until May launch, each car that was finished, was finished on special exemption, in order to be used for testing and exhibition purposes.

The Volvo control at Jensen Motors reported the finished and approved cars by using the office telex every Friday. The number of incoming bodies and delivered cars was included, as was the reporting of notification of changes and the follow-up of these.

Problems with bodies and supplier components

There were many problems with the bodies during the early stage of production. The need for correction was very large and all faults found were noted on so-called “body cards” and on each delivery, major faults were discussed by Volvo, Jensen and Pressed Steel. In a report from the turn of the year 1960-61, Arne Hasselsjö gave a most depressing report regarding the state of Pressed Steel bodies. This led to Hasselsjö being given the authority by Bengt Darnfors to hire two additional inspectors, to focus on the body quality. Two additional British inspectors were to be stationed at Linwood, under the supervision by Bernhard Hartshorn, and one more to assist with the Jensen body control when the bodies arrived from Scotland. The Linwood inspectors were going to be stationed along the entire process and in the pre-production sections, focusing on ensuring that the bodies that left Linwood were ready for painting at West Bromwich.

In January, R.A Jensen complained about the rising costs in a letter to Svante Simonsson. Cost that had been caused by rising prices on material and rising wages, on top of the costs agreed on in the 1959 contract. These costs were to be transferred to Volvo for pricing adjustment and payment according the the deal, but Volvo looked deeper into this before accepting and paying. The Jensen demands were investigated by Gösta Vallin and Thorsten Laurent, causing several meetings to be called during February and March.

By the end of January, R.A. Jensen now considered the first difficult pre-production period to be over and that the real production had begun. Svante Simonsson went over to Britain and was convinced that the body quality had improved somewhat which he informed about in a note, and that the rate of delivery from Pressed Steel by mid-January was eight to ten bodies per week with Jensen assembling five cars per week, These cars like the rest of the 250 cars, were shipped directly to Gothenburg for final inspection before being sent to the dealers as demonstrators or to eagerly waiting customers. From chassis number 250, cars were delivered directly from Jensen Motors to their final destinations.

Volvo and Jensen held weekly meetings with Pressed Steel, alternating between West Bromwich and Linwood. During February 1961, the discussions between Volvo, Jensen and Pressed Steel continued in order to find out whether it was possible to improve the quality level of the Pressed Steel and Jensen surface treatment. At one such meeting at Jensen, it was determined that the Pressed Steel bodies had unnecessary grinding marks left, probably caused by incompetent handling of the Pressed Steel tools. Volvo said that these marks could easily be removed from each car using electric hand tools and spending about an hour on the job. Such tools were not used by Jensen who still worked with files and grinding paper or emery cloths and could therefore not be carried out by them. A Jensen representative, Mr Collings, said that if they were to use machine tools for this grinding, a ventilation space had to be used and such a space was not available. The Linwood excuse was that the workforce was not trained properly for the job, but that an agreement had been reached regarding the quality stating that body no. 250 should be of adequate quality- By February 6, 1961, 62 bodies had been delivered, one had been returned to Linwood and there were three bodies at Jensen waiting to be painted.

Some bodies were very rusty on arrival in West Bromwich, causing a lot of extra work and had Jensen installing steam cleaning equipment. Still after deoxidising (phosphoric acid detergent) treatment, the bodies still looked dirty. In order to solve that, Jensen got new brushes and made special instructions on how to work with it. Also Richard Jensen pointed to this problem and considered the bodies inferior. At a meeting with Volvo’s men in West Bromwich, he said that he thought that the bodies coming from Pressed Steel were beyond description and the worst he had seen in his life. And Jensen was an elderly gentleman. He was astonished and regretted to have to see such bad bodies delivered from Linwood and that the workforce used there lacked any kind of skill and experience.

During the primer spraying process, dust and dirt from the painters clothing often ended on the surface, or entered the body. The same problem affected the application of the first layer of the topcoat. After having been through the oven, grinding scratches were fully visible through the coating but after the final layer had been applied they tended to disappear. During February the methods of applying the paint was improved. The nozzle air pressure was lowered which gave a much better result. After the final assembly, a number of corrections had to be carried out on the first cars and after they were done, the cars were thoroughly rubbed down. When doing this it became clear that Volvo quality required could actually be achieved by the rubbing of the body, possibly preceded by careful sanding in certain places This, however, was under the condition that approximately 10 to 30 microns of the top coat layer was removed in the process. The car number 12 was actually pointed out by both companies as an excellent example of the kind of quality that could be achieved. Volvo also noted that the painters at Jensen Motors successful in achieving Volvo requirements for finish, after making a great effort.

The crisis deepens

By mid March 1961, the situation at Jensen Motors was one of crisis. There was no more space for all the faulty bodies that had piled up. Tord Lidmalm came to the rescue and in a meeting between Volvo, Jensen and Pressed Steel, Mr Clark from Jensen said that Volvo had to stop the Linwood deliveries at once. Volvo obeyed, and until April 17 no deliveries were made. By March 20, 37 bodies, needed corrective work were waiting which made the assembly line come to a complete stop.

Volvo’s control people did their best but they could not approve bodies quicker than they did. The situation became difficult for Jensen to handle and they finally denied to unload any bodies that arrived on trucks unless the problems were solved at the source i.e. Linwood. Jensen required a general lowering of the final assembly quality level which was made, reluctantly. Volvo had already been forced to accept a lower quality and finish than usual on the first 50 bodies in order to have any cars assembled at all. Since Pressed Steel had been granted a running-in period of 249 bodies, with less than acceptable quality, Jensen thought that they should be granted the same conditions but this was not accepted by Volvo. Mr. Clark again pointed to the work of the Volvo control team who, according to him, wanted to modify and rectify cars all along the assembly process which caused costly and complicated breaks, and annoyed the workforce. If the production was going to be restarted, such things had to end. In order to get things going, the Volvo control team had to tone down their quality requirements on cars up to chassis number 150, nor matter what kind of defects were found. All subsequent work had to be carried out by the Gothenburg colleagues before delivery to their final destinations. By April 6, 1961, 168 bodies had been made.

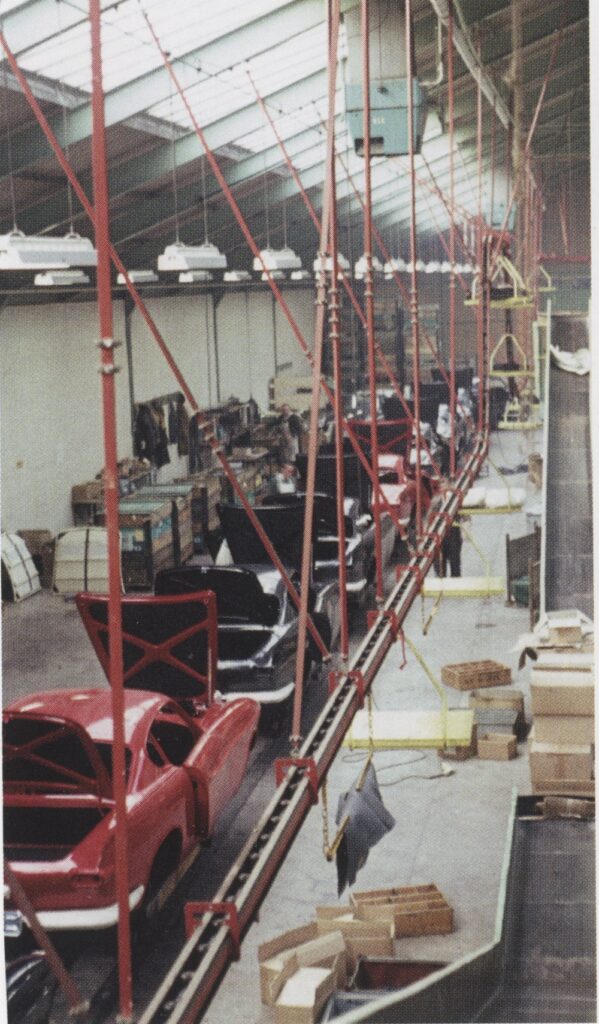

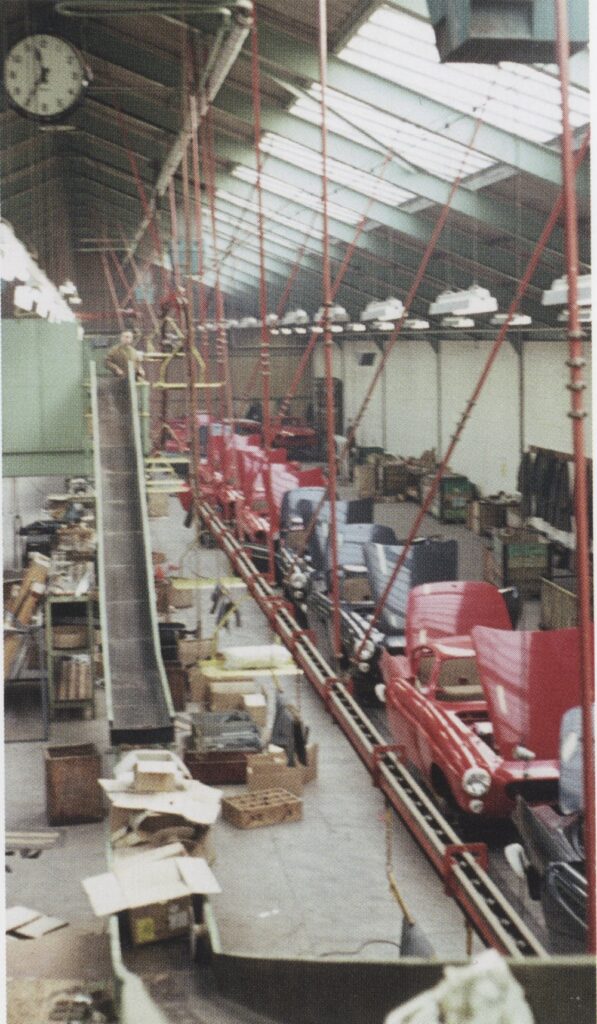

Between April 13 and 27, 1961, Mssrs Welin and Olausson from Volvo stayed at Jensen Motors. Their task was to study how the cars were produced and to suggest how to speed up the process. They reported back that they had been received in a very friendly way by the Jensen people, but due to the difficult material situation, they had not been able to carry on their work as intended, What they did notice, however, was a situation of disorder, close to chaos, especially around the assembly stations. This made it more or less impossible for them to identify more than just a few bottlenecks. Welin and Olausson both said that if the order and planning along the line was not re-organized and improved, then the future production would suffer a lot. The premises were considered adequate for the production of 200 cars per week, even for the twice amount of cars. The shortage of material was a major problem and affected the production for quite some time but in spite of this, the material stacked along the line was badly organized and scattered around on the floor since there were no shelves or boxes to store the material.

The P1800 assembly work at Jensen was carried out by working teams. Their different activities, with preparations of material, assembly and subsequent adjustments, meant that they move around all over the premises and to a certain degree used a kind of job rotation. This, however, affected the production negatively. For instance, if there had been a shortage of some parts and these parts had just arrived, the team that was responsible for this part, let’s say the doors, left their station when they were ready and went to work on the doors, no matter where in the flow they were, causing confusion. The same applied to after-adjustment which was done “before there was any after”, causing the ordinary work along the assembly line to stop. For example, only two cars were produced during one day in April as most workers required for the ordinary job were somewhere doing completion work, To solve this, Welin and Olausson suggested that the line was divided into stations, with as short working procedures as possible, which made them easier to learn and easier to carry out. A general inspection of the tool situation was also suggested to make the necessary completions. This was also done by Volvo. More fixtures and machine tools for the assembly work were also required and that the line was run at exact intervals until a continuous tempo could be used.

Welin and Olausson observed the lack of instructions for the workers; what to do, how to do it and what to use to do it. Rather basic really. Therefore they asked for special adjusting points with specially assigned assembly workers and that Jensen control inspectors were provided with better instructions. From their Volvo perspective. Welin and Olausson considered the working environment to be less than satisfactory. They had, for instance, to kneel on the floor to perform certain operations. Finally, a new assembly layout, including time intervals, was handed over. This, however, meant another reorganization of the work, with a high degree of responsibility and authority for those who would do it. The Welin/Olausson report ended with the following: “If a major part of what we have suggested is carried out, the place will be well suited for the production of cars even if the current situation looks a bit dark. When we came here, the fitting of the doors took 4-5 hours. By doing what we have suggested, the line work for doors will instead be a matter of 4 to 5 minutes”

Welin and Olausson made a final remark by saying that the costs that Jensen had to carry for the assembly work, were unnecessary high. The disorder that characterized the assembly work prevented the people for working efficiently. On the other hand, the tempo at which the work was done was not in any way near to what the Swedish workers had to do to earn the same amount of money. The relations between the workers and the management, on the whole, left a lot to desire.

The relations between Jensen Motors and Volvo went from bad to worse. Richard Jensen’s view on the spare part situation, from the Volvo notes taken at a meeting in May 1961, sums it up rather well: “Richard Jensen expressed his and his colleagues opinion that all faults that arise, and difficulties are to be blamed on Jensen while Volvo never makes any mistakes at all, and Pressed Steel is also without any blame. He thought that this was a very sad way of looking at matters, not the least because the future success relies on our cooperation, and he considered Volvo’s requirements in most areas too strict. The suppliers have now reached the point where future deliveries may be stopped. That, for instance applies to Sankey (bumpers) and statements like ‘Volvo can go to hell’ are not uncommon . Richard Jensen had been forced to intervene on several occasions. The quality requirements that are included in the agreement does not mentioned any Volvo standard but is comparable to the one considered as British automotive standard, and this should be kept in mind if matters were to develop into an open fight” One example of the inflamed situation was that Volvo’s head of control, Arne Hasselsjö, was prevented from making any protocols from the Volvo/Jensen meetings without first checking the contents with Volvo’ London solicitors.

In May 1962, major body quality improvements could be observed. One remaining problem area with the bodies was the upper front part of the door opening. This was, however, solved with lead fillings. For other problems, the pressing tools were improved and so was the design of the doors and their assembly and fitting. A key person in this work was Volvo quality engineer Bernhard Hartshorn. At a visit to Linwood by Tord Lidmalm, Sven Bengtsson and Bernhard Hartshorn during the last part of May, a body was picked out at random (body no. 414) and the 27 points of problems that had been identified before, were gone through meticulously. Recent improvements carried out by Pressed Steel, from body 331, were confirmed by the Volvo delegation and the visit was on the whole positive, considering the improvements carried out by Pressed Steel and their ability to follow Volvo’s intentions. Still, some minor improvements had to be done to make it easier for Jensen to fulfill the ambition to produce a good car.

Faults identified by Volvo’s delivery inspections

Some of the main problems for the P1800 production, listed here by Arne Hasselsjö and Gösta Lerström,, who were part of the Volvo control team in West Bromwich.

- Body problems -Jensen Motors put a lot of effort into rectifying the quality problems that surrounded the bodies when they arrived at Jensen from Pressed Steel in Linwood. The quality defects affected the joints between steel sections, the welding standard and damages. The bodies were delivered in batches of 24 bodies at the time on trucks. Many of the bodies were dented and uneven on arrival. Responsible for the delivery inspections was Jensen’s Mr Pritchard. Volvo purchased, according to the contract with Pressed Steel, bodies that were to be ready for painting which proved to be a problem. This was a very unlucky specification because there was still a lot of work to be done on the bodies before they could be painted. Jensen Motors used up a lot of lead filler when filling the cavities. An average of approximately 8 kg (15 lb) was used for each car. The smoothness of the surface was checked by pouring kerosene over the body before the painting process in order to detect irregularities but this was not enough. Defects were still found on the bodies after they had been painted which prevented the cars from being approved in the final inspection. Some times cars were brought back on to the production line to receive additional lead fillings and a re-spray. On top of this, the ICI paint was very sensitive to scratches. The cars were also leaking badly during the first period. There were for instance water leaks in the joints between the floor sections, most rubber seals and the rear quarter lights were also not tight. Proper water leak testing was nor carried out initially. Instead this was done in an ordinary car wash. This was duly questioned when Bengt Darnfors come to visit. Darnfors suggested that water was poured inside the body to check it for leaks, which also was done. This proved to be simple and efficient and led to the fact that bodies were subsequently welded and tightened on the inside.

- Chrome strips and ornament – Constant problem with the fitting. The so-called hockey stick on the doors were particularly difficult

- Rubber seal and strips – The rubber parts were of bad quality. To tighten the cars, foam rubber had to be put inside the hollow rubber strips to keep them ‘alive’ and elastic. and to meet the requirements for tightness between the doors and the body. One point of leakage was on the curved rubber sealing strip by the rear upper edge of the door. Here the solution had to be a complete redesign. A 90 degree corner was made into an S shape to prevent leakage. The angled side window were also letting in water, caused partly by the absence of a window frame. This design had most probably been chosen by Volvo to make it easier to make a convertible version of the P1800. The frameless window also caused a lot of infamous wind noise.

- Painting and finish – The cellulose paint and the assembly finish were not up to Volvo standard, Initially the sanding down of the primer caused trouble at Jensen caused by the preceding grinding work of the surface done at Pressed Steel. One problem with the paint was the existing small bubbles, Volvo found out that they appeared between the first and second lever of paint, caused by inadequate cleaning of the bodies before painting.

- Glass in general, rear window in particular – The first laminated glass used two layers and due to the slanted rear window, the vision was disturbed by optical distortion, especially when looking in the rear view mirror, The enlarging effect made cars like the Mini to take the size of a truck when appeared in the mirror.

This was just a few of the many problems that had to be corrected before the cars could leave the factory. Volvo protocols from 1961-62 mention the following parts and components affected by problems: hubcaps, quarter lights, front wing chrome, strips, doors, windscreen, rear quarter lights, rear window, steering wheel, the parking brake, brake rubber gaiter, rubber sealing strips for windscreen and rear window, rubber sealing strip for boot lid, courtesy light, window winding mechanism, upholstery, front and rear bumpers, revcounter, rubber seals for doors, gauges, head lamp bulb socket, speedometer wire and cable harness for RHD cars.

Working on the cars was also Gert Ganemyr. He confirms the problems mentioned, in the painting process and during assembly. On one occasion he wrote a very sharp letter, formally signed by his boss Tord Lidmalm and directed to Eric Neale at Jensen Motors. The most serious defects were listed and it was pointed out to Jensen that if improvements were not made, Volvo would not be able to fulfill its part of the agreement.

All cars that left the Jensen assembly line were finally approved and met the Volvo requirements. Still, Gösta Vallin wants to stress the fact that in spite of all the improvement work done in West Bromwich, the cars didn’t really reach a good quality level until they were brought back to Sweden along with the tooling and the production started here.

The very first production cars

During the spring of 1961, Volvo decided on how to handle the cars on arrival in Gothenburg. The first 200 cars were shipped from West Bromwich to Sweden for inspection and correction prior to delivery. To make the cars fit for delivery, the Volvo Customs department were on the arrival of the cars to report this to the Workshop planning in order to arrange the transport from port to plant, and make out a control card for each car, where all changes and modifications would be registered. Then the Car inspection department washed the car and went through them, noting every item that would be adjusted on the control card, and there were many. Then the cars were passed on to the Production department where an especially dedicated P1800 workshop had been established. The cars were adjusted on the basis of the control card and returned to the Car inspection department for final inspection. When the cars had been approved for delivery, they were reported ‘ok’ by the Workshop planning and handed on to the delivery department. The department that for one reason or the other had required cars via TSU (a special permit for expenses) were informed by the Order department when their cars could be handed over.

The car with chassis number 4 may well illustrate the width of Volvo’s corrective work. On inspection at Jensen, Volvo inspector Leif Olsson had made a made a list of 30 items (remarks and design faults) which was passed on to quality manager Helge Castell on January 31, 1961. The problem list contained, for instance, wrong fitted engine and steering wheel, bad fitting of chrome strips, lock cylinders wrongly fitted, bad paint finish, undercoating badly applied. After the control in Britain, number 4 was individually shipped to Gothenburg. The cars with number 3,6 and 7 were just as bad, inspected shortly before shipment along with number 5. They arrived in Gothenburg on February 20, 1961 on board m/s Suecia of the Swedish Lloyd shipping company. Other examples of problems were non opening quarter lights, boot lid hinges, wrongly positioned rear view mirrors and wrongly fitted driver seat cushions. An exception when inspected, a car without any major problems, was chassis number 14 with body 13 an engine 122.

Volvo kept the first cars for test and experiments for some time before the customer deliveries would begin. Chassis number 3 ended up in the hands of John Ståhlblad in the Engine design and engineering department. Chassis number 4 was taken over by transmission designer Inge Rose’n and number 5 was used by Gunnar Engellau as a demonstrator during a short period. After that it was used as spare part donor before fitted with new parts again and sold to a customer during 1961. Chassis number 6 was delivered to the USA in April 1961 and chassis number 7 went to the Volvo Styling department. Number 9 was used for laboratory tests and number 15 stayed in Britain and was used as a company car by the Volvo people stationed at Jensen Motors Ltd.

Per Gillbrand worked in John Stålblad’s department and was asked to do some special testing av chassis number 3. Gilllblad’s remarks were different to those made by the Control department in Gothenburg, but were straightforward, concrete suggestions for further development and improvements, to be passed on to the design and engineering colleagues who worked with the P1800; men like Gösta Vallin and Åke Björksund. Among the suggestions made by Gillbrand were and exterior bonnet catch, a new and better position of the heater unit in the passenger compartment and a better insulated gear lever rubber gaiter. Gillbrand also thought that the clutch pedal and gear lever were too far way from the driver and he also made a remark about the position of the horn and indicator levers which where in the way when handling other controls. Chassis number 3 was unfortunately scrapped in December 1961 after being severely damaged in a crash during testing.

During the last days of February 1961, Gunnar Engellau took the red number 5 on a trip to Malmö, some 300 km (190 miles) together with a man called Söderhielm and made notes about the car along the way. His observations were mixed. During the trip , a rather high constant speed was kept, approximately 130 kph (80 mph) but without pushing the car to its limit. Besides pointing out areas for improvement, Engellau also gave detailed suggestions on how to make them. The safety belt kept sliding off his shoulder, the seats were too high; the instrumentation was difficult to read; disturbing reflections in the windscreen during darkness; the widows were practically impossible to operate without using force. The engine, the performance and brakes were praised, so was the road manners of the car. A few weeks later, Engellau to a white car for a spin, probably number 3 or number 6, and noted the same things as he had done with the red car plus noise from the rear suspension, squeaking brakes and a sluggish gear change. Engellau liked the driver’s position but remarked once again that the windows were practically impossible to open.

He was also disappointed with the toolkit that he though were bad beyond description and made a cheap impression. Furthermore, the tools had already started to rust. Engellau said he had not seen such a lousy spanner since he had his first bicycle as a boy. The first cars were built at a very slow pace. The first car to be reported ready was chassis number 2, on December 20, 1960. Then the production went as follows: two cars ready in January 1961 (chassis number 3 and 4) three cars in February (chassis number 5,6 and 7) eight cars in March (chassis numbers 8,9,11,12,14,16,18 and 20) and nine during April (chassis number 10,15,17,21,23,25,29,35, and 41) During the month of May 1961 an additional 66 cars were built and in June 241. It is worth to note that chassis number 1 was not reported ready until June 2, 1961. Volvo and Jensen worked intensely to make as many cars as possible before the 1961 summer vacation and by July, chassis number 400 was passed and the production staff worked during the their vacation in order to ship cars that were ready for delivery.

When doing the reseach for this book, the first 300 production cars have been mapped out. Of these 300 cars, traces of 174 have currently been found but far from all have been located or can be accounted for. Of the first production cars, the following are known and still in existence: 1,2,4,10,11,12,14,16,20,29,31,33,36,37,38,47,and 49

Major problems on early cars

At Volvo in Gothenburg, it was decided that in connection with the delivery of each car from England to Sweden, Volvo’s foreign control notes and remaining faults on each car as well as Jensen Motor’s control card would be sent to Sweden to Volvo’s control department so that Volvo could quickly get an overview of the extent of the errors and for the necessary follow-up of the development of events. A man named Benny Borsing joined Volvo in 1961 at the age of 17. He worked on what was called the “Old 7” in the vault at Volvo in Lundby. There they had a workshop where Volvo did all the extra work on the series cars. Borsing says the early cars were delivered in batches of about 25. All the flaws were corrected and there were problems with seals, things that were loose or did not work. The biggest problem was that water was leaking. There was a flushing hall that cars were driven into and some of those who were driven through the water test were so leaky that you got soaked. It was so bad that hardly anyone wanted to do this test. Borsing aimed doors and windows in the workshop before conducting the test so that there would hopefully be less water leaking in when conducting the test.

Many of the very first P1800 cars could not really be considered finished when they left the factory in England. From the minutes compiled directly by Arne Hasselsjö during the inspection in England in the spring of 1961, it appears, among other things, that the following:

• Chassis No. 11, 12, 13 and 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20: The engine sat too high (about 15 mm.), the steering wheel had sharp edges, the ashtray was sloppy, the seats were too high, the door fits were poor, door windows, ventilation windows with locks and elevators were of poor construction, puttying of the front and rear windows was not performed, brake and gasoline pipes were poorly drawn, the tools were of poor quality, Glass for the number plate lighting fit poorly against the back cover, drop strip at the right rear side window had to be adjusted in, problems with overdrive at 30–40 km/h. Furthermore, both the padding and the black ornamental strip above the storage compartment in the rear seat were wavy, welds at B-pillar were ugly, sheet metal and painting finish inside were poor, the carpet fit poorly at the handbrake lever, grille rail was unevenly adjusted, ornamental moldings at rear side windows were dented, 2nd gear was hard to get out of, frame for roof fabric vibrated at the rear. Chassis number 13 was completely looted, probably as a result of a lack of parts, but was reassembled in the autumn of 1961 and delivered on 1 December 1961 to Göinge Bil in Hässleholm where it ran as a demonstration car

• Chassis No. 21: Ornamental strip right front fender was wrong. The other ornamental moldings were dented.

• Chassis No. 10:Right door tightened. Buttons were not mounted in mats. Ornamental strip left side window needed to be replaced. Ornamental strip right front screen needed to be changed.

• Chassis No. 24: Mid-section bumper front was dented. Buttons in floor mats were missing. Number plate lighting did not fit against the back cover. Ornamental moldings were petty. The fresh air intake was a bad fit. The door glass did not stand against the rubber moldings. Painting around ceiling fabric was not good. Ornamental strip that was mounted instead of the masonry clan pushed rubber moldings into the seal. The gear lever vibrated.

• Chassis No. 25:Ornamental strip on drip strip was dented. Buttons were missing from the mats. The ornamental strip at the left rear side window needed to be replaced. The ornamental strip on the left front fender needed to be changed. The left taillight was crooked and had to be adjusted.

• Chassis No. 27:Ornamental strip at the left rear side window needed to be replaced. Buttons in carpets were missing. The gear lever vibrated.

• Chassis No. 28:Buttons were missing from the mats

As late as April 1961, just a week before the series-produced car was to be shown publicly to motoring journalists, extensive faults still remained on the cars shipped to Gothenburg for completion. All cars had to be fixed in various respects and unfortunately not all faults had been fixed before deliveries of the cars began. The reasons for this were partly the constructive design and partly that there was still a lack of real details to a large extent. Helge Castell at the control department reported that as long as these faults existed, it was not considered possible to “OK” the cars as they did not represent the Volvo quality that a finished car should have. Here’s how the remaining remarks were summarized:

1. Clapping noise from gear lever with suspension. The noise was very unnerving and was present on all the cars. It was heard especially when shifting and was not of the nature that it could be accepted.

2. Strong wind noise from the front edge of doors. The wind noise occurred where the outer sealing strip ends. The noise of the wind was heard at the ventilation window brace.

3. The door glass sealed poorly against the sealing strips. Water and air leakage.

4. The sealing strips for the doors were hard and unwieldy. The moldings didn’t stick together in the corners. The joints must be taped together with plastic. This lasted for a while but after a few door closures, the joints went up again.

5. The sealing strips were of poor quality, especially the tailgate.

6. Rubber moldings for rear side windows had a very poor fit inside. The lip stood from in the front and in the corners.

7. The ornamental moldings were petty. There was no better material to switch to. The ornamental moldings on the squares were poorly fixed. The flange in the rubber strip was too narrow and too hard.

8. The rear windows showed twisting images.

9. The right rear handbrake wire lay against the exhaust pipe, causing rattling and noise.

10. The jack was against the spare wheel and not in position in bracket on side board. The mount was too low and too weak and the cardboard did not hold.

11. The door glasses were loose and not stably attached, which caused them to flutter at higher speeds.

12. The hood latch rattled.

13. The choke lever did not bring the fuel nozzles back to the correct position after choking, which caused the carburetor setting to go wrong with abnormal fuel consumption as a result.

14. The choke control was very sluggish even after adjustment and was difficult to maneuver.

15. Front door gables were poorly painted, only brush-improved, and the surface was poorly cleaned before varnishing.

16. The sheet metal work inside was not good. Windshield poles and moldings had bad surfaces, ugly welds, etc.

17. Improvement paintings in England were not of any higher class. The surface was poorly cleaned underneath and it was difficult to redo so that acceptable paintwork could be obtained.

The Volvo P1800 is shown to the Public and the press

For many years, Volvo’s customers around the world had been asking if Volvo could not design and manufacture a more sport-oriented car, but based on and built on the essential mechanical components of Volvo’s then passenger cars. Two years had passed since the first official news about the P1800 was released until the first manufactured cars were delivered, but now it was finally time! In connection with the presentation, Volvo described that the outer design of the car was made by Frua in Italy and that in the car’s lines you could find much of the Italian style that was currently leading the way in the world’s automotive industry. By the end of April/May 1961, 59 P1800s had arrived in Gothenburg. During the first week of May, 20 were unloaded and the following week another fifty or so sports cars. Around week 18, chassis number 86 was arrived and by week 21, chassis number 200 was estimated to arrive in Gothenburg.

In early May 1961, the Volvo P1800 sports coupe was introduced in Sweden. On the square outside Hotel Fars Hatt in Kungälv, Volvo showed some of the first production cars, two white and one red. For practical reasons, the viewing took place over two days. The first day was 3 May and then there was a screening for the Danish and Norwegian press, TV and some Swedish news agencies. The next day it was the morning press’s turn in the morning and the afternoon press in the afternoon. The viewer was largely the same for all groups and began with a review of technical data, manufacturing and sales points around the P1800. Gunnar Engellau, Gerhard Salinger, John Stålblad and Åke Larborn were responsible for these information. The invitees were then given the opportunity to get their own idea of the car through a test drive. As you could then read in the newspapers, there were positive reviews. On May 5, one car was then exhibited in Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö each. The introduction of the P1800 also gained space on the airwaves of the news program TV-aktuellt during this week. The union press disposed of three cars for testing at the end of May. The introduction on the European continent took place around May 20.

Some of the cars that appeared at screenings and tests in the trade press during the spring and summer of 1961 were chassis number 52 (registration number OA 27002), chassis number 54 (OA 27003) and chassis number 56 (OA 27004). These cars were PR cars that Volvo used in advertising and exhibition contexts during the very first time, before they ended up at dealerships and then came onto the market. There are not many contemporary moving images of the first generation of P1800 cars, either in Volvo’s or Sveriges Television’s film archives, but from a longer film presentation about the Volvo companies from 1963 there is a short film sequence with a red P1800 in 1961, and it is precisely one of the above-mentioned cars namely chassis number 54.

A technical presentation

Volvo showed off the new sports car to enthusiastic journalists and the reportage unanimously testifies to a positive car experience. The car was available in three different colors: white (color code 69) with red interior (code 301), red (color code 70) with white interior (code 302) and grey (color code 71) with red interior (code 301). All three versions were decorated with black moldings and the interior was perceived as tastefully designed. The dashboard and sun visor were mattressed and the seats could be set up for the correct individual driving position. The trunk was considered spacious compared to other sports cars and the car, like Volvo’s other passenger cars, was equipped with seat belts, electric windshield wipers and windshield washers.

The P1800 was considered by many as a comfortable and stable GT car for fast long journeys. Instead of being 45 kilograms lighter than the prototypes’ 1045 kilograms, the lowest empty weight had increased by 55 kilograms. Nevertheless, it was found that the car’s performance was stumbling close to a sports car’s 0–100 in 14.5 sec. Volvo’s engineer Gerhard Salinger described the car in the following words: “The prerequisite for the car is that it is a sports coupe, not a racing car. This means that it is a complement to Volvo’s regular passenger car line. passenger car comfort has been maintained: i.e. high suspension comfort, good sound insulation, good tightness and proper car heater with a special fresh air system, while the new engine gives the car superior performance. Through constructive measures, the P1800 has a completely superior road holding.”

The seats had been designed to provide a comfortable and steady driving position, but an excessive bowling had been deliberately dispensed with. The designers did not believe that a bowling could be made effective if it would suit drivers with varying body measurements. Should a bowling be effective, the seat must be tailored to the driver in question. Instead, the basic prerequisite for a steady driving position during hard cornering had been achieved, namely a proper support for the left foot. The support was located at exactly the same distance from the chair as the accelerator pedal, and its tilt corresponds to approximately half throttle. The space in the back seat was not excessively large. This is what Motor wrote in 1961: The doors are wide and open well, which facilitates entry and exit into the low car. Thanks to the door width, you can also relatively easily enter the spare space behind the driver’s seat. A couple of children can ride along without sitting too folded. Security had been given great care. The car was equipped with seat belts as standard and it had proper leg freedom under the dashboard. After all, the seat belt was stretched in the event of a crash, when the occupant was thrown forward and then a large legroom was required. Of course, both dashboard and sunscreen were mattressed.

The magazine Motordriver: Swedish-Italian alignment has included in the Volvo P1800 an appealingly elegant association. You enjoy how easily you keep unusually high cruising speeds on good roads and it is an experience to hold off on hilly roads. The car is located all the time as if on rails even on gravel-covered roads. Volvo’s sports car is an excellent alternative for those who want a fast, comfortable, road-safe and easy-to-drive car at a good purchase price and low operating cost. Target price incl heating, seat belts, windshield washer, free Gothenburg SEK 17950. For overdrive, SEK 650 is added.

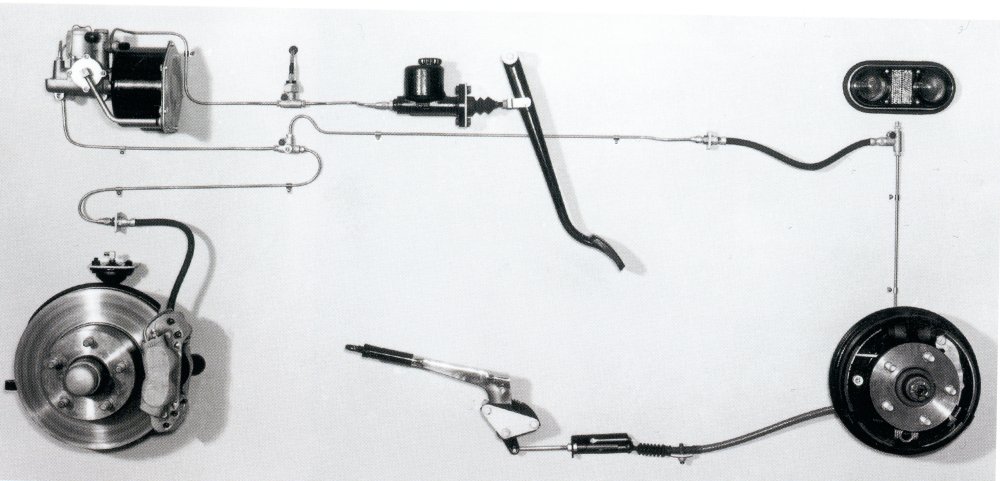

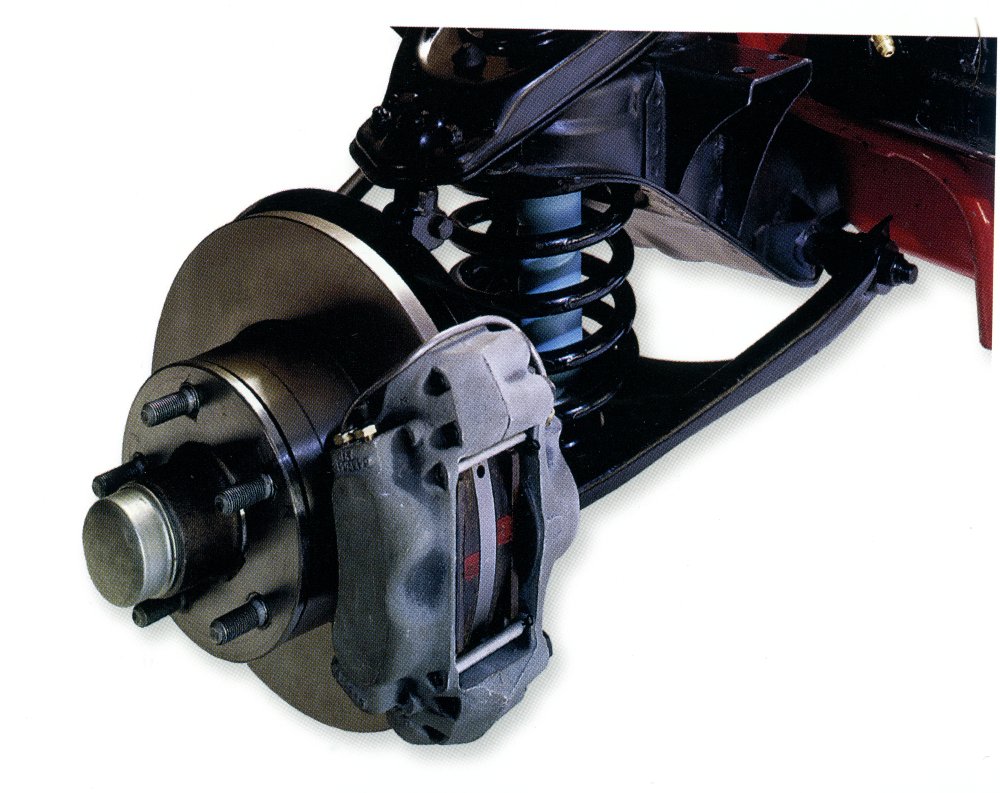

DN magazine: The plus side: Good brakes, Durable engine. Minuses: body unsightly, too small tank. On the front wheels, the car was equipped with new three-cylinder disc calipers with easily replaceable brake pads. At the rear, the car had self-centered drum brakes. The car had 15″ wheels, fitted with belt-type sports tires with dimension: 165×15″. The car was equipped with a 12-volt electrical system. In addition to the usual control lamps, the instrument panel also contained speedometers with both road and trip meters, tachometers, water and oil temperature gauges, oil pressure gauges, fuel gauges and clocks. The P1800 also had dual horns with specially operated strong-tone signal.

As for the power transmission, the gearbox was the same 4-speed box (M40) used in the rest of the passenger cars. The gear ratios were exactly the same, with the difference that all the forward gears’ drives had been needle stored. This was a design finesse common to pure sports cars. The car was delivered in two designs. Either with gearbox M40 and rear axle gear ratio 4,10:1 = P18394 A or with gearbox M41, i.e. 4-speed box plus overdrive with rear axle gear ratio 4,56:1 = P18395 A. One of the two additional accessories that customers could choose for the Jensen-built cars was thus an electrically operated overdrive manufactured by Laycock de Normanville, with gear ratio 0,76:1. With it, the final gear was 4.56:1, otherwise 4.10:1. The overdrive was marketed as a very interesting option, which allowed the P1800 to be considered a 5-speed car. It used the four regular gears for acceleration and then used the fifth gear as a road gear. The overdrive was easy to put in and out of because the clutch pedal did not need to be used and the overdrive also contributed to a significantly better fuel economy. Two-spoke wooden steering wheel was the second accessory.

Engineer Salinger continues: “As an example, if you drive at 100 km/h on overdrive at a constant speed, the consumption will be only 0.7 liters/mile. The consumption of the P1800 in general is even lower than that of the 122S provided that you charge the same amount of power. Since the cars is faster and allows greater power output, it can generally be said that fuel consumption is largely unchanged compared to the 122S. The P1800 has not been geared to be able to go at the absolute maximum possible speed. Rather, it has been shifted to achieve the best possible acceleration. The maximum speed is thus just over 170 km/h. Acceleration performance is 0–100 km/h through the gears in just over 13 sec. These values apply with the load of two people.

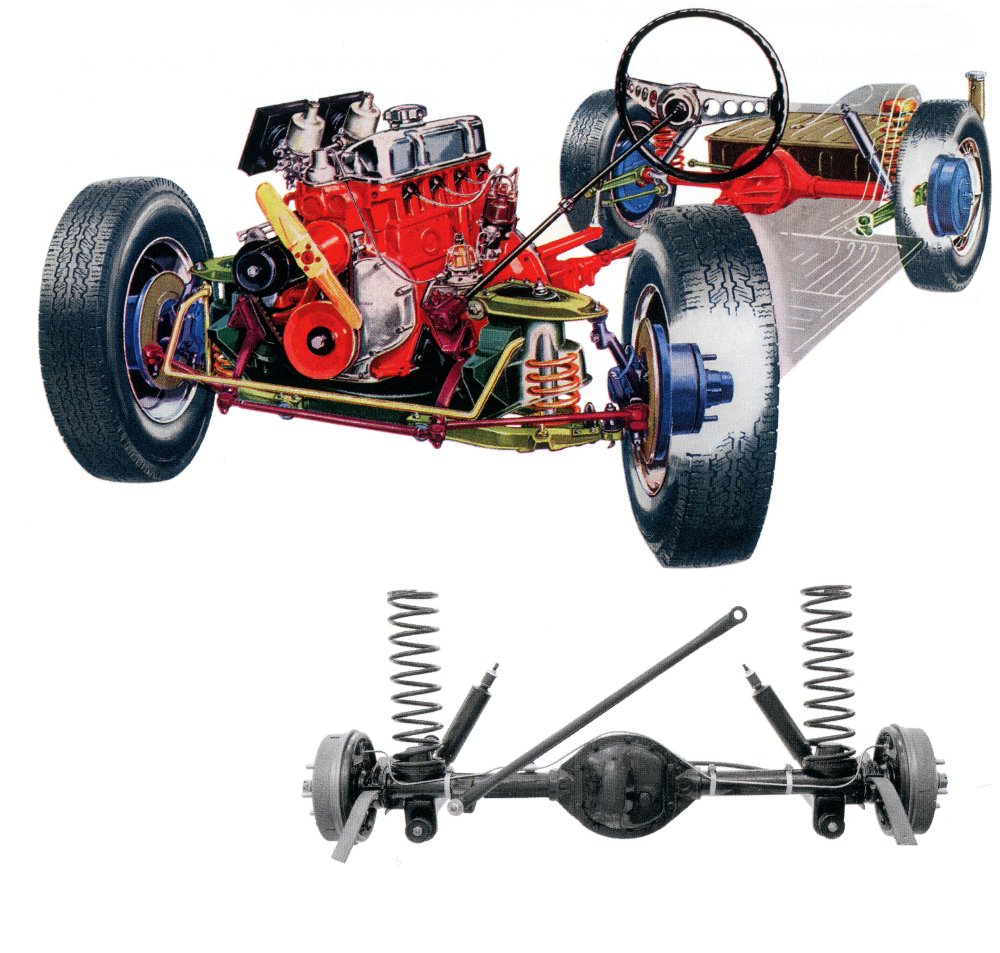

Chassis and body

Most of the chassis details had been taken over from the Amazon. Thus, the P1800 had coil springs all around and it also had the special Volvo rear axle suspension, i.e. a suspension where the steering of the rear axle was handled by special carrier arms and a transverse strut, where for the suspension used coil springs and one for damping shock absorbers. These were on the P1800 of special sports type with a special freon-filled nylon cell, which allowed them to withstand high temperatures without impairing the cushioning.

The P1800 had been given a shorter wheelbase compared to the Amazon (2.45 metres instead of 2.60 metres), the centre of gravity had been lowered, the heel inhibition was increased at the front, spring constants and shock absorber settings had been fitted to the special tyres with which the car had been fitted. These tires were called belt tires (German: Gürtelreifen; English: Belted tiers or Radial Ply Tyers). For example, when a tire picked up lateral forces when cornering, the tire deformed. In an ordinary tire, the deformation was absorbed into the tread, which was relatively soft compared to the stiffer tire sides. This tread consequently, when deformed, provided a not entirely perfect plant surface. The belt tyres worked basically the other way around, by putting a rigid belt under the tread, while the deformations were taken up by the much softer tire side. The result was a larger and better plant surface that allowed greater forces to be absorbed when cornering, driving and braking. In addition, there was a greater service life of the tire and almost no tire scream when cornering. The disadvantage of this tire consisted of hard and bumpy running at low speed, but by adapting the spring and shock absorbers, they had managed to give the P1800 an acceptable driving comfort at low speed and somewhat fantastic driving comfort at higher speeds. With these constructive changes and adaptation to these special tires, Volvo had managed to achieve a surprisingly good road holding of the P1800.

The biggest news on the chassis side was otherwise the disc brakes. The design of the disc brake was distinguished by the fact that it allowed for significantly better cooling than a drum brake did. This could be noticed already at occasional braking from very high speed as the deceleration was about the same at 150 km/h as at 50 km/h. Improved cooling and resistance to decreasing braking performance could be noticed above all during repeated braking. Another feature of the disc brake was that it allowed good pedal force gradation. In other words, they can get the desired deceleration by using different pedal force. The P1800 was equipped with a brake servo to achieve low pedal forces, among other things, considering the future female drivers of the P1800.

Engineer Salinger also highlighted the design and function of the car as follows: “Volvo wants to give the P1800 a timeless shape. It has the classic, soft sports coupe lines and has intentionally not been made fashion-bound. If you like, you can see the P1800’s shape as a synthesis between yesterday’s angular style, the so-called trapezoidal line (see Fiat 1800) and today’s round style (see Ford). The body is, of course, self-supporting. The interior, of course, is elegant and lavish, which is required in such a car. Above all, the instrumentation is unusually extensive. For except for an electric tachometer, an oil temperature gauge is included. On the right under the steering wheel there is an unusual lever. With it, the special stronghorn is operated for road driving, while the normal signal is, as usual, located in the middle of the steering wheel. In summary, the P1800 can be described as a car, where passenger car comfort has been maintained in all respects and which has also received good performance and outstanding road holding.

It is a known fact that Pelle Petterson’s connection to the P1800 has come to be surrounded by some rumors. When the first series-produced P1800 was shown in public, Pelle’s name was not actually mentioned at all and the Gothenburg newspaper is said to have written “Volvo Sport ready for display” without touching the local designer. Volvo’s official description was that the P1800 was: … a combination of Italian design, Swedish quality and English craftsmanship. However, the newspaper Expressen had learned of how things were and in the review of P1800 in Bil-Expressen on July 9, 1961, Lennart Öjesten wrote that: The designer Pelle Petterson has succeeded well, most people probably think so. Although Pelle’s efforts were not mentioned to a greater extent, there is no doubt whatsoever about Pelle’s involvement in the P1800, nor is there any doubt about this fact on Volvo’s part. But, as Pelle Petterson himself puts it in Bengt Jörnstedt’s book, “Pelle P. – sailor, designer and winner”: “Oddly enough, I didn’t attach myself to it. I knew how Volvo reasoned, their image and status would be chipped away at. I was just grateful to have experienced this job

The delivery situation during the spring of 1961

The situation at the beginning of May was that nine cars were delivered outside Sweden for demonstration and exhibition purposes, while eight cars were disposed of by Public Relations and Advertising for testing, demonstration and exhibition. Four cars were delivered in-house for other tests and chassis number 64 was delivered to Princess Birgitta, who incidentally had a petrol stop on her P1800, which is said to have been caused by a hard-to-read petrol meter. Ten cars were delivered to the United States for demonstration and exhibition around May 20, and likewise, ten cars were delivered to continental Europe for the same purpose. Due to Volvo’s dissatisfaction with the lack of finish of the very first series-produced cars from Jensen Motors, it was decided that the first 150 cars would only be delivered to Swedish and foreign dealers for demonstration purposes and not delivered directly to end customers, which was followed with a few exceptions.

Intensive work was now awaited in Volvo’s product department and an extensive chamber to inform and involve Volvo’s dealers so that they could arrange local press screenings and exhibitions. The advertising department in Gothenburg provided the retailers with special introductory sets containing brochures, minifolders, specification sheets and postcards describing the P1800. In addition, a number of posters were sent out intended for indoor use. In order to support the local introduction of the P1800, sketches of podiums for the car were also sent out that could be ordered from the advertising department, or have been manufactured locally. The advertising department also gave suggestions on how poster columns could be built and that “streamers” for the storefronts could be used and on what ads could look like. Furthermore, dealers were provided with a black nameplate in the size of 70×100 cm, with technical data on the car and invitation cards for distribution within the sales district.

By the end of May, 107 cars had arrived at Volvo in Gothenburg and 59 cars had been checked, completed and delivered according to Volvo’s reception and delivery routines. It is worth mentioning that chassis number 1 was not yet fully completed by now, but that car was intended for Volvo’s internal disposition in the PR department (styling). According to Volvo’s delivery program, approximately 45 Swedish dealers would have received one copy for demonstration purposes by June 6, and with a continued stable delivery rate, all Swedish main districts would each have received a copy of the car around the turn of the month June / July 1961. By the end of June, 287 cars had arrived at Gothenburg. The deliveries to the Swedish customers began in earnest around July 10. At the end of May, the current order backlog amounted to 170 cars and according to Volvo’s delivery plan, which was based on Jensen Motors’ delivery capacity of 75 cars per week, these cars should have been completed around the turn of the month August / September.

Many eagerly awaiting customers found the P1800 to be a quiet, solid and comfortable grand-touring car with good driving characteristics, eye-catching lines and performance that was adequate if not exhilarating with a top speed of 175 km/h. However, there were also negative reactions aimed at finishing, opacity and rattling. In the US at the end of June, the order backlog of 778 cars for deliveries to the US was high.

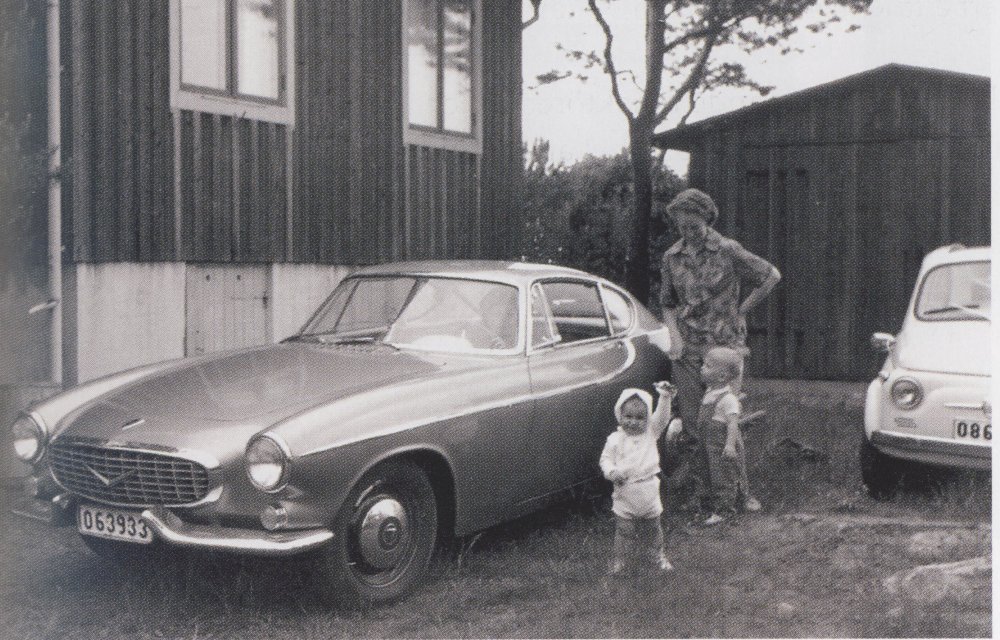

In the Volvo dealer showroom 1961

This is what it could look like in a car showroom in 1961 when Volvo’s dealers proudly showed off the new sports car. The photos come from Arfwidson’s family album showing the hall where new carriages were presented. Bil AB Nils Arfwidson’s showroom was located in central Södertälje and adjacent to the premises there was a small office. The volvo trade itself was located in other premises on the outskirts of Södertälje. In order to get the car into the showroom, in the evening when there was little traffic, you had to remove the shop window and build a ramp for the car to get over the high edge. The exhibition of the P1800 attracted a lot of people who were amazed by the new Volvo. Not many customers ordered a P1800, but against that, several customer contacts were created, which in turn generated orders for new Amazons and PV. It was a very successful outcome, exactly in accordance with Volvo’s conscious strategy when the sports car project was launched.

One of the P1800 cars sold by Bil AB Nils Arfwidson was chassis number 196. It was delivered to Mr. Douglas Salin in Bromma at the end of June 1961, but already on August 18 and with only 919 miles on the meter, Mr. Sahlin came back with the car to his Volvo dealer. When he arrived at the workshop, it turned out that the car was completely wet inside the trunk as well as inside the canvas mats and door panels. It was inspected by Anders Grundberg at Volvo’s service department. Grundberg summarized some crucial reasons for the leak, namely that the luggage rack was not cut up at the drain holes and poorly pasted, that the ventilation windows were too tightly clamped, a strong leak at the seater and a minor leak from the upper rear of the left front fender. The car should also have been subjected to rough treatment with a flush hose, which could have caused this moisture damage. However, the customer was naturally dissatisfied with the situation and demanded a completely new car as a replacement. After investigation and discussions between the owner, the dealer’s workshop, Volvo and the Motormen’s National Association, it was finally agreed that the car should be prepared in the best way, after which the Motormen’s National Association would inspect and conduct a thorough test of it. An extensive work card containing 38 errors was fixed before Mr. Salin got his sports car back.

In order to stimulate sales of the new sports car, Volvo attracted its Swedish sellers by, among other things, arranging trips abroad for successful dealers.