Green light for the sports car project

The project is slowly preceding

Five design proposals are presented

From Frua’s prototypes to the sports car

The first prototype chassis

Carozzeria Pietro Frua – quick and efficient

Carozzeria Pietro Frua

Carozzeria Pietro Frua builds the P958-X1

The history of the P958-X1

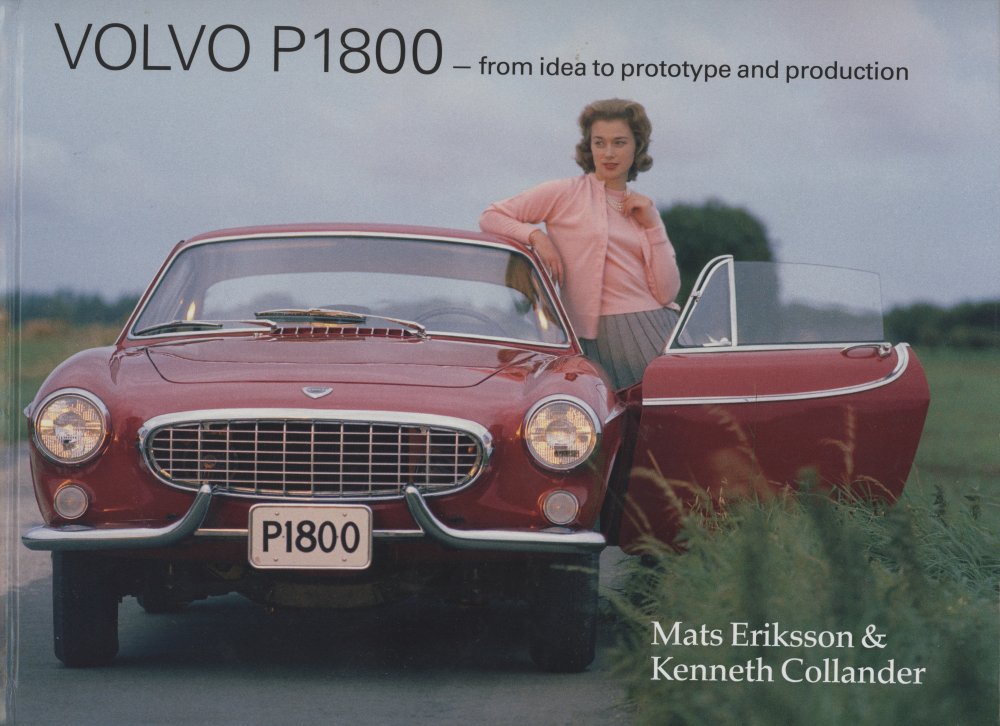

Green light for the sports car project

In May 1957, Pelle Petteson’s studies in the USA came to an end and it was time to return to Sweden. During the past two years, he had learned a lot and had many exciting experiences. Above all, Pelle had been given the opportunity to pursue his interest in cars. During the last semester, his studies had been focused on means of transport, with a great focus and a lot of sketching on cars. Back home in Sweden again, Pelle’s dreams of becoming a car designer came true and he had the opportunity to help his father, Helmer in Volvo’s “secret” car project. The month before, Gunnar Engellau had given the green light to go ahead with the project to develop a sports car prototype in Italy, on the condition that the car exuded Italian exclusivity and design

By and large, it was only for Pelle to pack his suitcases again, this time to head down to Turin in Italy. There, Helmer had arranged a position as a designer at the company Frua, a subsidiary of Ghia, which collaborated with Helmer to develop the sports car. With this, Pelle would forever write himself into Swedish car history. When Pelle arrived in Turin in early summer and the assignment was presented in detail, Pelle had already had time to think through how he wanted the car designed. He had an edge over his colleagues and continued to draw and improve the sketches he had already started on during his last semester at the school in the United States. An important inspiration for Pelle’s work in designing the sports car was the French-American design icon Raymond Loewy. He was the man behind the design of Lucky Strike’s cigarette box, the Coca-Cola bottle and the very characteristic Studebaker cars from the late 1940s and early 1950s. In Turin, Pelle also got a free outlet for his racing instinct. It was an environment steeped in performance ambitions where every ounce would be sucked out of a car engine. Pelle’s colleagues and new Italian friends tuned their cars and Pelle did what he could with the Volvo Amazon he had down there. On the Monza track, there was a chance to race against each other, to the extent that they did not now do so on the usual country roads.

The project is slowly preceding

The work of developing the sports car continued and Helmer Petterson had continuous contacts during the spring of 1957 with Wilhelm Karmann GmbH, which at that time was the intended manufacturer of the sports car, and with Ghia, which was already in the process of developing the prototype. Helmer, however, had different challenges than Pelle. He worked in the longer term to try to enable the manufacture of the car in series production. A conference at Volvo on June 27, 1957 was attended by Tor Berthelius, Gösta Vallin, Helmer Petterson, Bertil Bengtsson and Per Ekström. It mentioned, among other things, that Volvo would provide details according to the established specification and that larger units would be sent directly from main suppliers to Karmann in Osnabrück. In a letter from Karmann on April 24, 1957, it was specified that in the case of an order for 5000 cars, one could undertake to manufacture the car at a cost of SEK 3825 at a rate of 10–12 cars per day. This would then include all assembly. Volvo’s calculation for a finished car in Osnabrück included its own material as well as Karmann’s manufacturing and tooling cost, which ended up at SEK 8535 per car for 5000 cars. The calculated sales calculation in Sweden said that an estimated price to the customer was assumed to be SEK 15000 (excl. excise duty / oms) and Volvo’s profit would then be SEK 3760 for contributions to tool cost and trading expenses. At this point, Volvo’s economists did not calculate that the sports car would generate any large surpluses for AB Volvo.

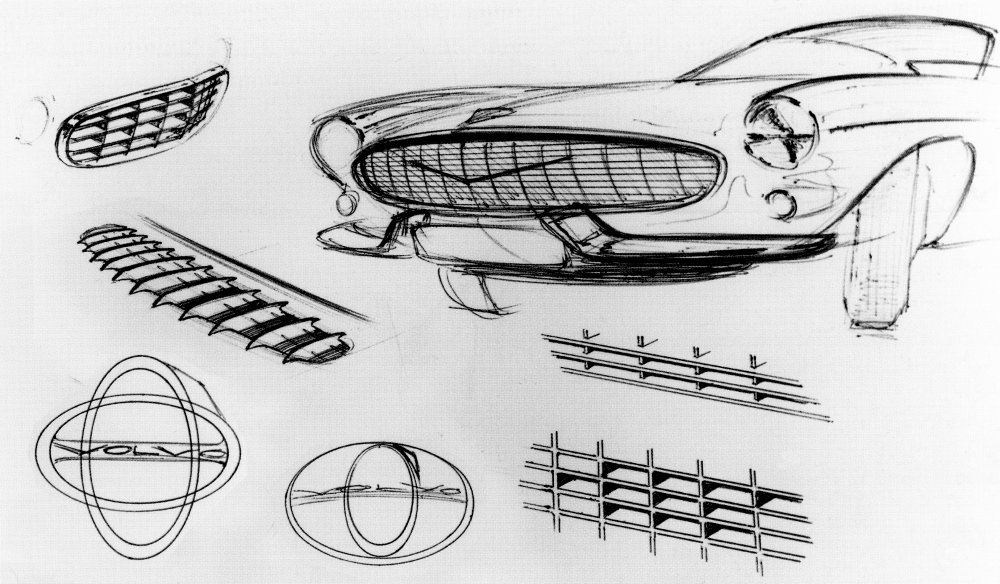

Five design proposals are presented

Now that Pelle was a designer at Frua, his father was worried that he would not be allowed to help with the work on the car. He therefore did not tell Gunnar Engellau that Pelle was employed at Frua. During the summer of 1957, Volvo’s management wanted to see the completed proposals for the design of the sports car and in July 1957 five different sports car proposals were ready to be sent to Volvo in Gothenburg. Two were made by designers at Frua, two came from Ghia and one came from Pelle Petterson. Pelle’s proposal was the only one that was colored and with shadings. The proposal was of high professional class with elegant perspective drawings that revealed his skill with the pen. The training had given Pelle an edge on his design competitors to more easily sell his creation. The secret lay in working with the right paper and pens. While the other proposals were similar to sketches, Pelle’s living was alive in a very different way. When Luigi Segre, manager at Frua, saw how well Pelle had developed his proposal, he asked Pelle to also redraw the others’ proposals in the same style so that they could make a similar presentation to Volvo. Pelle did this reluctantly because he was not particularly fond of the other proposals. The drawings for his own proposal were completed between 29 and 31 July 1957, 31 July was also Pelle’s 25th birthday. Pelle continues. “It was the case that the Volvo management chose the proposal that I had developed. I had done some sketches, one of which was almost identical to the end result. But at least it was that sketch plus a few more that Volvo management fell for. At the time, the sketches weren’t signed and they didn’t really know who was behind the sketches. After some time, my father had to tell president Engellau that it was the “kid” who had done the sketches. And it did raise some questions because it kind of spoiled what Volvo was looking for, that it would be an Italian car. And if it came out that it was a little boy from Sweden who had been responsible for the drawings, and together with Helmer made the car, then it would interfere with the image of the product. So there was a call from the Volvo management to keep silent on who was behind the actual design. This, then, is the explanation for why Frua officially got the merit of the design, and not Pelle Petterson. Today, however, there is no doubt whatsoever on Volvo’s part as to who did what in terms of the car’s original design.

From Frau’s prototypes to the sports car

The concrete work of building the handmade prototypes was carried out by Ghia’s subsidiary Frua in Turin. Ghia had a contract with Volkswagen which prohibited them from working with possible competitors of Karmann Ghia, which is why Frua was commissioned to develop three handmade prototypes, which later came to be called P958-X1, P958-X2 and P958-X3. Frua’s team on site was reinforced by father and son Petterson. No other Volvo personnel participated down in Italy at the prototype stage. Now the project was full speed ahead and Helmer was happy and satisfied, now the close cooperation between father and son that Helmer had hoped for and dreamed of in the US letters to Pelle, had finally been realized. Project manager Helmer Petterson was responsible for the chassis technology, which was based on amazon components. Pelle honed his sketches and was given a free hand for the design of both the exterior and interior, although Pelle was given some help with the model work by Frua’s foreman Nocolotti. Much of the secret of Pelle’s winning proposal lay in the trade-off between the neat southern European shapes and lines influenced by the American cars, such as the characteristic fins at the rear. Pelle told me that thanks to his father’s and his own preparatory work, he was largely clear about what the car would look like already when he arrived in Turin and that he could then seriously begin his sketching of most of the details; everything from the instruments, controls, steering wheel and door panels to the front and rear seats, knobs and door handles

The first prototype chassis

Åke Björksund was employed as a newly graduated civil engineer at AB Volvo Cars on July 1, 1956 as a draftsman and designer and worked in various positions within Volvo until 1992 when he accepted an offer of “contractual pension”. Björksund’s first assignment at the passenger car drawing office included work with a cardan shaft and rear car for Volvo Amazon where he, among other things, lowered the rear car by 25 mm. Åke Björksund says that he was already involved in the new sports car project at a very early stage. Björksund says that already after the New Year 1957 there was a what one might call uneasy atmosphere at Volvo in Gothenburg and somehow it was clear that there were secrets going on. While Pelle was polishing on the looks, the Helmer designed the chassis base, which as far as possible was based on a shortened floor slab from Amazon. Åke Björksund’s responsibility was to design the chassis, a task that Tor Berthelius and Raymond Eknor had, under great secrecy, given Åke Björksund and his colleagues at “PR” (Department of Passenger Car Experiments) in Lundby in May 1957.

The task was to develop three identical chassis for the new sports car. According to the requirements specification, the sports car was to be based on Volvo Amazon in 1957, but be 150 mm shorter and 20 mm lower than this. Björksund became project manager and was responsible for all the technical details that the three chassis would contain and all the new features that would be fulfilled. The deadline given to Åke by the Volvo management to complete the task with the chassis was 1 October 1957. The concrete efforts to design the chassis were carried out by Åke Björksund himself and the assembly of the beam system, floor and intermediate board on the chassis was carried out at the Olofström factory.

In August after the summer holidays in 1957, Åke Björksund himself traveled down to Olofström by truck to bring home the first chassis for the sports car. Björksund says: “Due to the strict secrecy that prevailed, I myself traveled down from Gothenburg to Olofström during the night and came back with the chassis only in the morning. I felt that the atmosphere at this time was quite heated and the pace of work was high, but despite these conditions, the requirements specification was met and the delivery time was kept.” After the assembly of the front and rear axle as well as the drivetrain (engine, transmission and rear axle), the finished chassis were transported down to Frua in Italy. The first chassis was sent to Frua in Turin on August 24, 1957

Åke Björksund continues: “The big technical challenge in the creation of the chassis for the sports car was to achieve a steering system with good steering geometry and with the least possible changes to the amazon details in the front suspension. The amazon petrol tank was originally to be used without modifications, hence the prototypes’ tank filling on the right side. Instead of moving the muffler to the left side of the serial cars, it was decided to make a new tank top and move the fuel filling to the left side. Another hard-to-crack nut was the handbrake system. Here Björksund found a solution where you could use a lot of the amazon details. The second and third of the Frua prototypes both had a hanging handbrake lever under the instrument panel, unlike the first car to have the handbrake lever mounted like the Amazon 1957, rising out of the floor to the left of the driver’s seat.

Carozzeria Pietro Frua – quick and efficient

On September 10, 1957, a representative of Carrozzeria Pietro Frua sent a letter to Gunnar Engellau. In the letter, Frua confirmed that it had received the assignment from Helmer Petterson to deliver the first prototype as well as two additional cars. Volvo wanted the first prototype completed as early as 15 November. Frua told us that the first chassis arrived in Turin on September 6. In Frua’s original offer to Volvo as of July 9, 1957, it was stated that Frua would need five months to manufacture a prototype, which meant that the deadline for the first prototype would be February 6, 1958. It turned out to be faster than that. Work progressed rapidly with the first prototype. At the same time, Frua expressed in the letter that they would “prioritize this work and work at no further cost for the prototype to be ready before the end of 1957”. For the wooden model, Frua said they needed at least six weeks and estimated that it would be ready on October 15, 1957. At the same time, they expressed some concern about not having time to go from finished wooden model to complete car with all the details in just two months. They ended the letter by indicating that they were prepared to finish the remaining car at the total cost of $5500, after about 3-4 months from the time the decision was made regarding the first prototype.

Carozzeria Pietro Frua

Pietro Frua

On May 2, 1913, Pietro Frua, the son of Angela and Carlo Frua, was born in Turin in northern Italy in an area that was the center of Italian automobile manufacturing. Pietro trained as a draftsman, constructor, designer and graduated from the Scuola Fiat in Turin in 1930. His professional career began with a job with Stabilimenti Farina as a draftsman/constructor and after only a few years of work, he was appointed head of the design department at Farina, a company that employed several hundred people and was a leading car design company in Italy at the time. It was also then that in 1936 Pietro made his first contact with his lifelong friend, Giovanni Michelotti, whom he hired as an apprentice.

In 1937, Pietro Frua quit Pinin Farina and Giovanni succeeded him as head of the styling department. It was hard times for him in his early years as a freelance designer during the war, but he made it and got a few occasional jobs. He designed, among other things, cars for children, electrical equipment for kitchens and a scooter. He had wide plans for the future and then started up his own design company “Carozzeria Pietro Frua” and in 1944 he bought a broken boom bath factory, which was prepared and equipped to design and build cars. The company was to employ about 15 people. It can be mentioned that Frua hired Sergio Coggiola who later became famous and opened his own design studio. Maserati was one of the first customers to come to Frua to receive design proposals for its new sports car, the A6G. Frua’s first really famous car was a 1946 Fiat 1100 Sport Barchetta. From 1950 to 1957, Frua built several Spyder and coupe models in three different design series.

In 1957, Carrozzeria Pietro Frua was acquired by Carrozzeria Ghia. At the time of the purchase, Pietro Frua was appointed head of Ghia’s design department. One of the reasons for the acquisition may have been that Ghia and Luigi Segres wanted to use the Frua brand, a possible reason could be that the main customer Fiat could not accept that Ghia’s name was used by Fiat’s competitors. During the period of the collaboration between Frua and Ghia, the three prototypes of the Volvo P1800 were built at Frua. It was to be a short collaboration between the companies. Frua was responsible for the design of the successful Renault Floride, which had great commercial success. However, the success led to disagreement between Segre and Frua over who the car’s originator was, which is said to have resulted in Frua leaving the company and restarting her own design studio “Studio Technico Pietro”.

Pitero Frua’s work direction and philosophy was to be so involved in each car project himself that he himself would be able to follow the practical implementation in the smallest detail from the beginning to a fully functional product, sometimes driving them himself after completion to various car fairs in Europe. Frua came with his various companies to be one of the most prominent brands of Italian car design and body building between 1950 and 1970. During this era, Pietro Frua came to create about 100 cars for various companies. Some examples are: Volvo, BMW, Maserati, Fiat, Peugeot, Renault, AC and Opel. Some of the cars that Pietro Frua had been involved in were the Fiat 1100TV convertible, Peugeot 203, Renault Dauphine, BMW GT, AC Frua Spyder and Fiat 600.

In 1963, at the age of 50 and at the peak of her career, Frua designed a GT Cupé and a convertible for the car company GLAS. These cars came to be produced until 1968, but then as BMW GT, after BMW bought up GLAS. In the late 1960s, Frua tried in vain to extend their successful collaboration with GLAS by making a dozen proposals to BMW, but instead BMW decided to do the work on its own. During the 1970s, the frequency of his presentations decreased. He began to step down and end his professional career, to hand over to the subsequent generation of car designers. There was also no longer any requirement or demand to build detailed and functional prototypes in just a few months. In 1983, a few weeks after his 70th birthday, Pietro Frua married Gina who had long been his assistant. On June 28 of the same year, he died in the aftermath of a cancer.

Carozzeria Pietro Frua builds the P958-X1

During the autumn of 1957, hard work was done to complete the first sports car prototype, all according to Pelle’s design proposal. Pelle transferred the sketches from the winning design proposal to full-scale working drawings with dimensions of the car. Pelle says: “Based on these drawings, a three-dimensional “shape” was constructed that was built in wood by skilled carpenters, the work was done in a similar way whether it was a boat or a car. The lines were drawn up on longitudinal and top cuts and the various wooden parts were screwed and glued together into frame boxes. The shapes of the body were planed and then sanded out of the wooden frame, and with the help of “templates” it was periodically checked that it became the correct shape. Once the craftsmen had found out the exact body shapes of the wooden structure, it was tested on the bottom plate that had wheels, drive train and engine mounted, it was important to check that the wooden structure looked good and that everything fit in place on the bottom plate. The location of the wheels in the wheel arches, the location of the steering wheel and the fact that the engine did not come into contact with the inside of the bonnet, this was the matter of millimeters.

When everything fit, the manufacture of the sheet metal body itself began, the various body parts were knocked forward by hand over the wooden model, it was impressive to look at how the Italian sheet metal workers shaped the plates, they knocked, used stretching machines and heated heated the metal the metak sheets. And there was also a bit of tin putty at the end, once the plates had been mounted with millimeter fitting on the bottom plate.

When Volvo developed the plastic car Volvo Sport, it had largely started from the existing parts that were already on the market, both its own, others’ and standard accessories. Unlike Volvo Sport, it was now a different mode, it was “Petterson-designed” components that had to be developed which required a lot of preliminary work, with extensive travel and contact creation at various companies in Europe that manufactured car components. An important man in this context was K.G. Knutsson, who helped Helmer Petterson with components for the sports car. Among other things, Hella, Bosch and ZF were visited, where Helmer brought drawings. The deeply bowled instruments were manufactured by VDO, a company in Germany and materials for the interior design of the latter two prototypes produced in 1958, came from Hornschuh Weisbach. Many of the details such as grille, bumper, door handles, buttons on dashboard as well as chrome moldings and emblems were made by hand in Turin. There was a group of specialists who carried out these special works, which included saddlery and interior work. All while the prototype was being manufactured, various tests were done with B16B engines that Italian Abarth had tuned. These engines were assembled and then tested in Volvo Amazon.

At the end of 1957, the first prototype P958-X1 was basically assembled and ready, although it was still not fully drivable: “I wanted the front to be lower and if the engine could be tilted, the front end could have been lower, but it didn’t work. I felt bound by the undercarriage, I would have liked the car lower , but above all I would have liked wider wheels and wider track width. However, the shoulders could not accommodate wider rims. The wheels were too thin and the car looked a bit feminine, but by and large the car met my expectations as it had emerged.

Pelle goes on to talk about when the P958-X1 was finally finished: “Yes, here the car is finished and you could test it, here we see, among other things, what the original wheels looked like once in the world, and also some other gadgets such as the Volvo emblem, but were also criticized for it as someone back home in Sweden had views and said you were not allowed to have Swedish flags and crowns on the emblem. Yes, then the Volvo typeface as well, which was very strange, but I didn’t matter, just thought was funny.” In connection with this, Pelle’s work on the prototypes of the sports car was almost complete and he made only sporadic visits to Frua during the time when prototypes 2 and 3 were being manufactured.

The history of the P958-X1

The prototype P958-X1 was the first of three prototypes produced at Frua in Turin. All three were handmade and the P958-X1 was not completed to full drivable condition until early 1958. The car in 1958 received the designation P958-X1 BLUE. The car was originally green/blue metallic with light beige interior and yellow rims. The P958-X1 was inspected and approved in Sweden by Carl L. Engström and Rolf Öberg on April 2, 1960 and registered with AB Volvo in Gothenburg as owner in April 1960. After the interim registration number O1305, the car received its official registration number O63933, where the letter O represented Gothenburg and Bohus counties. When the car was finished using in connection with tests, demonstrations and other things, it was put away at Volvo’s Lundby factory in Gothenburg in early 1961.

One of Volvo’s young engineers, Sven-Olof “Esso” Andersson, discovered the car one day under a tarp in one of Volvo’s parking lots in May 1961 and contacted his colleague Gert Ganemyr to investigate whether he could buy the car. Contact was then made with Tor Berthelius, who was the head of the passenger car drawing office. Volvo was not used to such issues and there were some difficulties with pricing the car. After some discussions with colleagues, Berthelius concluded that everything was in order and behind his mahogany desk Berthelius let Esso Andersson know that: “The cart is yours. It was decided that Andersson would be allowed to buy the car from AB Volvo for the purchase price of SEK 2000 and it was subsequently registered with him as owner in June 1961. According to the agreement, Andersson undertook to … not drive the car openly until Volvo’s deliveries of the P1800 to customers have started on a larger scale, which was expected to take place around July 1, 1961… and used the car with caution, but went to Dalarna in the summer of 1961 to visit his parents.

Shortly after Andersson bought the car, he received an offer from Volvo to travel over to England and work with the P1800 at Jensen Motors Ltd. in West Bromwich and the work was mainly about handling design issues at the factory. When it became clear that Andersson would succeed Volvo’s representative for construction, Sven Bengtsson, at the Jensen factory in West Bromwich, Andersson stored the car with a good friend, watchmaker Elis Åkerblom in Borlänge. Said and done, Esso went to England and P958-X1 had to wait for its owner in a free space in a workshop in Borlänge in Dalarna. There the car stood until he returned from England in mid-1963 after taking part in the work of finishing assembly in England and preparing for the relocation of the production of the P1800 to Sweden. Only then was the car brought home to Gothenburg and Andersson began to dismantle and renovate it.

One day Andersson was contacted by Volvo’s control department in Gothenburg. They had a production-made body from Pressed Steel in Linwood that had been used for measurement, probably in connection with preparations for the repatriation of the production and assembly from England to Sweden. The control department asked Andersson what to do with it. The conversation resulted in Andersson having to buy the body primed for SEK 300. At that time, the P958-X1 was partially dismantled in Andersson’s garage on Windmill Street on Hisingen in Gothenburg. Andersson decided to rebuild the P958-X1 into a new car and use the newly acquired body and front and rear car from P958-X1 as well as some new and better used parts from the so-called “Wolf Cage” at Volvo. Andersson also had good help from Volvo’s purchasing department. The extensive rebuilding work took place in Andersson’s garage in Gothenburg. The result was a completely new car containing a mix of components from, among other things, the newer P1800 and a new body but with original rear and front car from the P958-X1. Andersson bought a test engine (B18B) and a gearbox from Volvo and had the body “Volvo white” painted in Kungsbacka. Andersson painted the engine compartment black and used some furnishings that had been discarded by Jensen Motors in England. He assembled the new car but retained the registration number O63933 from P958-X1. The emblem behind the rear side windows was missing on the “new car”. Andersson used the car for a time, but then sold it on to Motorcar in Gothenburg.

This, prompted by the sudden availability of a completely new body resulted in the embryo of two cars having emerged. The “new” car was re-registered on March 1, 1963, taking over the P958-X1’s chassis number X1, the type designation P958 and the 1960 model year. The type plate for the “new car” punched Andersson himself. The “new X1” was re-inspected on June 9, 1964 by Roland Broo and remains to this day with registration number FPH 155. The car has been refurbished and is still white.

Then what happened to the original P958-X1 body? Well, Andersson asked the handy designer at Volvo, Arne Hultberg, if he wanted the Frua X1 body. He accepted. Hultberg got the body and interior but Andersson kept the front axle, rear axle and steering gear for the “new X1”. Arne Hultberg did extensive work on the renovation of the P958-X1 body and procured the remaining parts for the car when he revived and renovated it in his garage in 1964. Arne Hultberg was also the first owner of the first left-hand drive Jensen-built prototype P1800-X1. For the P958-X1, he used, among other things, the front and rear carriage from an Amazon and mounted a dashboard and front window of series car design. When the car was fully renovated in January 1965, it was provided with new identification documents and a new chassis number (X010) as well as a new type designation (Volvo P1800A). After it was then registered, it was bought by one of Hultberg’s childhood friends, the teacher Ragnar Brattborg in Uppsala. Brattborg registered the car in January 1965 and used it until it was decommissioned in February 1972. On April 29, 1982, a new registration certificate was issued for the same car, which resulted in a new registration number (BYU 651). The reason for this change is probably that the registration fee to the Swedish Road Administration had not been paid during the time the car had been decommissioned, which generated a need for a new registration inspection. Today, the car rolls in the Gothenburg area with Jonas Kjellberg as owner.