Starting time – at last

Specifications for the Volvo P958

Wooden model for the press tools

Pressed Steel Company Ltd

Jensen Motors Ltd

The manufacture of press tools

Linwood to handle the body assembly

Spare parts

Stirling Moss tries the P958

Volvo new sports car go public

Final assembly at Jensen Motors Ltd

Paint, trim and customs matters

Starting time – at last

Gösta Vallin told us that one day Tor Berthelius returned to him with news that the Volvo management had made a decision to start the P958 and at the same time T.G. Andersson had come to the decision that the assignment should be carried out by Pressed Steel Co. Ltd. in the case of “body in white ” and that Jensen Motors Ltd. would be responsible for the rest of all the body parts, painting and final assembly. Volvo would deliver the powertrain, etc., and otherwise assist in all the issues that would arise in the process. Raymond Eknor was given responsibility for the construction of the body and Gösta Vallin was responsible for the chassis.

In the autumn of 1958, Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors were visited for short periods by Vallin who became acquainted with the people with whom he would later collaborate. Vallin could spend a week in England and then about 4-5 weeks at Volvo in Sweden. Tor Berthelius had suggested to Gunnar Engellau to put Vallin on the task of coordinating the activities between the three parties and this meant that Vallin would gradually become a permanent resident of England. Simply put, Vallin would have the role of Berthelius in the England project. Together with T.G. Andersson, Vallin traveled over to Jensen Motors where Vallin was introduced. Except for the small information about the project that Raymond Eknor had already conveyed to Vallin, he knew at this time nothing about the background, who made the models and how the prototypes had been transported around Europe. When Vallin first came to Pressed Steel, he was very surprised that they had already gained access to the third prototype P958-X3 for measurement.

Specifications for the Volvo P958

The final specification for the production of the Volvo P958 was established on December 12, 1958, replacing the current version of the “Specification of Volvo P1200X” from September 15. Åke Björksund was deeply involved in the work on the specification, from which it is clear which parts the various players Volvo, Jensen Motors Ltd. and Pressed Steel Co. Ltd. would be responsible for and deliver to the assembly plant at Jensen Motors in West Bromwich. Björksund and Leif Fridén spent about two weeks producing two identical archives of drawings that would then be used by Pressed Steel and Jensen Motors.

The specification stated that Pressed Steel was responsible for the design and production of the body and that the design would be made in such a way that any later convertible version would be easy to produce after the necessary reinforcements had been mounted underneath. Volvo decided that a completely new set of pressing tools for all the sheet metal parts of the body would be manufactured. No sheet metal parts would be manufactured in Sweden, but the sheet metal parts that were identical to Amazon’s would be manufactured by Pressed Steel based on drawings handed over by Björksund.

The original idea of using existing components from Amazon had long since been scrapped, which meant that the sports car would be a completely different car from the base in the form of an Amazon 1957 model year on which the car was originally developed. Furthermore, it appeared that Jensen Motors in England was responsible for the construction of lighting, embellishment details, glass, dashboard and interior details, as well as painting and final assembly of the car. Volvo was responsible for the design and delivery of mainly the engine, gearbox and some parts of the front and rear car for Jensen Motors. The gearbox would be an M4 and the 5.90 x 15″ low-profile type tires with 4.5″ rims manufactured by Kronprinz.

In the specification, Volvo also listed the details that needed special approval by US authorities. The details would be sent to the U.S. for approval before Volvo could start delivering series-produced cars. These details were; headlights, parking lights and turn signals, brake lights, number plate lighting, turn signal controls, window glass, reflectors and seat belts.

Wooden model for the press tools

As early as December 1958, Gösta Wallin was in the process of planning and had, among other things, discussions with H. Barber, who was responsible for the body construction at Pressed Steel Co Ltd. They reasoned, among other things, about the amount of wood that should be ordered for the wooden models for the different body parts. Tor Berthelius and D.D. Hobday at Pressed Steel concluded on New Year’s Eve 1958 that an order for “2,000 square feet, one inch thick impregnated mahogany for Wood models” would be sufficient. The mahogany was purchased by Haskelite Manufacturing Corp. “Hasko-Preg” in Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA, which at this time was the center of the U.S. furniture industry. In July 1959, the wooden models at Pressed Steel were created based on Frua’s prototype P958-X3 and on July 16, Gösta Vallin approved the modified wooden models for the pressing tools. For the first layout, Pressed Steel used aluminum and then a set of templates was made that would be complete enough to be able to produce and control the pressing tools.

Pressed Steel Company Ltd

Pressed Steel Co. Ltd. was founded by the renowned motorcycle and automaker William Morris, who had founded the Morris Motor Company as early as 1910. Pressed Steel Company Ltd. was a British company that started its business in 1926 producing pressed sheet metal parts and body metal bodies for cars in Cowley near Oxford. William Morris had seen advantages in the production of pressed steel parts for the automotive industry developed at The Budd in the United States and interest was aroused in a collaboration between the companies. In a joint business agreement between William Morris, Budd Cor poration and a U.S. bank, the newly formed company started its business of supplying car bodies to Morris in a factory facility near the Morris Motor Company. After nine years, Budd withdrew from the collaboration and by 1935 Pressed Steel was completely independent and was then able to produce car bodies for competing car brands. By the late 1950s, the company had expanded and manufactured pressed steels and whole bodies to most major automakers in the UK such as Rolls-Royce, Standard Triumph and the Rootes Group.

Jensen Motors Ltd

Jensen Motors was a British automobile manufacturer, active in West Bromwich, England during the years 1935-76. Brothers Alan and Richard Jensen began making handmade cars in small numbers in Birmingham in the 1920s. All the cars were special orders, which were built on behalf of the customers according to their wishes. The engines were purchased from Ford or Chrysler. One of the first missions was to rebuild an Austin 7 Saloon into a more sober 2-seater car.

The manufacture of press tools

According to the new production plans for the sports car developed in collaboration with Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel, it was intended that series production of the sports car would be up and running by September 1960 at full production rate (100 cars per week) achieved by February 1, 1961. This would correspond to an annual rate of about 5000 cars in 1961.

Pressed Steel’s mission was to develop a completely new base plate for the P958. As early as 9 October 1958, one of the three Frua prototypes, the steel-grey P958-X3, was shipped to England with m/s Britannia and then transported by lorry to Pressed Steel in Cowley outside Oxford where it arrived on 22 October 1958. There, it served as a model for measuring for the design and development of the pressing tools. It is documented that the car was at Pressed Steel on October 30. Åke Björksund, who was present at Oxford, says: “They made templates or profiles along the body surfaces and put them up in a coordinate system. Based on these templates, drawings were then made to be able to manufacture the pressing tools. There were rigorous safety regulations at the site and the time pressure was great.

Based on Åke Björksund’s drawings, work began in early 1959 on the construction and production of the pressing tools for the body.

In February, the second prototype P958-X2 from Frankfurt-am-Main was sent to Cowley, while two baseplates were also delivered to Cowley from Olofström in Sweden. The idea was that Pressed Steel would be responsible for the P958-X2 and one of the bottom plates later being forwarded to Jensen Motors. These arrived in Harwich at the beginning of the month of March

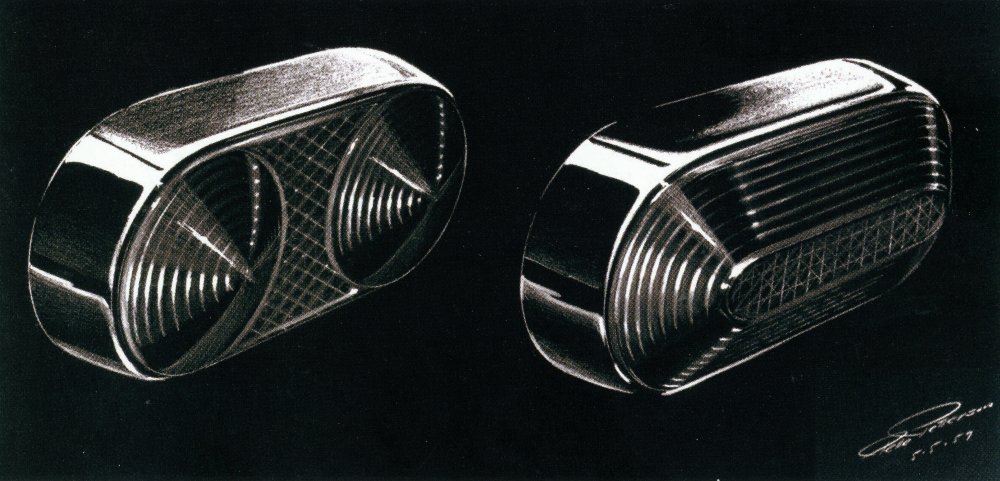

In the spring of 1959, Pelle Petterson was also again involved in the project. Pelle was commissioned this time to design a new design on the stern. He had been given “back homework” about the location for the number plate, as it could not handle all sizes of plates. Pelle therefore had to draw a lighting that stood out and illuminated a plate that could take all possible sizes

It was probably in connection with these events that both the P958-X2 and P958-X3 had their rear sections rebuilt to the design that the Jensen-built prototypes P1800-X1 and P1800-X2 later came to have. The most eye-catching modifications on the rear end consisted of mounting a volvotext, changing tail lamps and number plate lighting, and removing the recessed rear number plate and exhaust pipes that went through the rear of the body. “The arrangement with the exhaust pipes going out through the rear end was neater, but impractical,” Pelle says.

On October 1, 1957, Tord Lidmalm took up the position of Technical Director for the design departments and technical development departments at AB Volvo in Gothenburg. He came most recently from Svenska Aeroplan AB (SAAB) in Linköping. On April 1, 1962, he became a member of the Board of Directors of passenger cars, retaining the headship of the Construction and Development function. On July 6, 1959, a delegation from Volvo paid a visit to Pressed Steel in Cowley. The delegation consisted of Tord Lidmalm, Gösta Vallin, Tor Berthelius, Helmer Petterson and Pelle Petterson. The purpose of the visit was to approve the wooden models for the British prototypes before they would be taken over by the machine shop at Pressed Steel. The points that underwent the last changes before the models were approved by Volvo were the areas around the A-pillar, rear fender, rear piece and rear lamp width.

Based on approval by Volvo, Pressed Steel’s sheet metal workshop at the design workshop in Cowley created a handmade body that was then transported to and assembled at Jensen Motors Ltd. This car, designated P1800-X1, became the first English-built prototype. All body construction for the sports car was carried out at Pressed Steel in Oxford. Åke Björksund says: “The plate for the P1800-X1 was hammered out after the first drawings in so-called hammer molds consisting of a tool half and a so-called stamp in the form of a rubber tool into which the plate was pressed. No real fixtures were used. I myself performed bending and stiffness measurements on the first sheet metal body at Pressed Steel in Cowley, Oxford.” Incidentally, in the same place where they worked with Morris and Rolls-Royce. Björksund continues: “At the workshop in Oxford, there were probably a few more test bodies made at the prototype stage”.

During 1959, the periods that Gösta Vallin spent in England became longer and longer and he carried out regular reports on the situation to Tor Berthelius every Friday morning by telephone. The reports concerned, among other things, the extent to which each party had obtained documentation and what efforts were required to speed up or help Jensen motors in particular, which was constantly lagging behind. Initially, Vallin expected to have to spend more time at Jensen Motors, near Tipton in Birmingham, than at Pressed Steel with its main plant in Cowley, Oxford. Somewhere between these resorts he planned to search for quarters and the choice fell on the Raven Hotel in Droitwich, a scant hour’s drive from Jensen Motors and about a three-hour drive from Oxford. The visits to Pressed Steel were made as agreed at about three weeks apart as they kept meticulous minutes and discussed openly about the progress of the work. In a few cases, Pressed Steel wanted changes to Volvo parts to facilitate its assembly. On every other or every third visit, Pressed Steel’s chief engineer attended, otherwise it was a nice young man who led the project at Pressed Steel and he had 3–4 men at his disposal. The large outlay was made as usual in those days in full scale on lacquered aluminum sheets.

Linwood to handle the body assembly

Late in 1959, the chief engineer of Pressed Steel announced that the assembly of the body would be located in Linwood, which is located just outside Prestwick at Glasgows Airport, i.e. in Scotland. It came like a flash from the clear sky and the reason given was that Pressed Steel was far too overcrowded in Oxford. Pressed Steel invited Vallin with several others on a private plane to Prestwick to show the factory, which was in full swing and at the time producing Hillman bodies. Parts of the factory were brand new and during an hour’s viewing Vallin could not remark on anything special, but it was already known then that Glasgow suffered a lot from the shipbuilding crisis and Vallin guessed that the workforce came from the shipyards and was not very knowledgeable in handling structures in thin sheet metal.

Quality manager Helge Castell says the decision by Pressed Steel to move body production from Oxford to Linwood in Scotland came as a total surprise to Volvo, which had nothing to oppose the decision because there was nothing in the formal settlement with Pressed Steel to prevent them from changing factories. Castell remembers the disorder in the oxford factory. The premises were poorly cleaned with Swedish Volvo standards measured and there were goods in the transport aisles, but unfortunately also some wrinkles in some sheet metal parts that were manufactured there and sent to the body assembly in Linwood. At the factory in Linwood, there was a rural atmosphere. It was to some extent an older factory that had previously manufactured railway cars, a product with not too high demands on finish in relation to the quality requirements of a sports car body. The workers were still relatively unschooled and untrained in their new work with body plate with significantly higher requirements for surface finish and good fit in relation to railway cars. The discussions regarding quality, surface finish and fits were not infrequently lively and the differences in the quality culture were worrying and did not seem to contribute to a particularly easy-to-work process between the parties. Together with his manager Bengt Darnfors, Helge Castell also participated in later negotiations and re-negotiations between Volvo and Pressed Steel regarding body production.

All pressing of sheet metal parts for the series-produced bodies and their actual final assembly took place at Pressed Steel’s production facility in Paisley, Linwood. After the final assembly of the body, the bodies were treated with a rust retardant, in this execution the bodies were called “Body In White”. The bodies were then transported south by rail to Birmingham where they were reloaded to lorries to travel the final distance to Jensen Motors Ltd. in the West Bromwich Midlands where they were to be painted and fitted into a complete car. Volvo probably did not realize, here at the drawing stage, the seriousness of this turnaround and Pressed Steel’s choice of Linwood as the place for the body’s composition. It would prove to be far more significant than could have been calculated beforehand.

Spare parts

Already in early 1959, the parties worked on resolving all arising spare parts issues. Volvo promised both to Pressed Steel and to Jensen to place specified orders for spare parts for the P958 by March 1960 at the latest. The goal was for these orders to cover the estimated need for spare parts from September 1960 until December 1961. Volvo judged that the most urgent spare parts order was the one for Pressed Steel, which should be extensive. Jensen’s spare parts deliveries were expected to be of a much smaller scale, primarily relating to bumpers, radiator grilles and other ornamental details. In both cases, Volvo planned to buy the parts at the supplier’s factory. In order to fulfill specified orders for spare parts for Jensen and Pressed Steel, T.G. Andersson estimated that it would probably be necessary sometime in the early 1960s to station a couple of spare parts specialists with the relevant suppliers in connection with the establishment of the necessary specifications. T.G. Andersson also noted that orders for spare parts in small quantities are likely to be very expensive, especially when considering the size of the two companies Jensen and Pressed Steel. Jensen, in turn, planned not to manufacture any parts for which they were responsible, but to buy all of them from subcontractors and it was regulated in such a way that Volvo had no right to buy directly from them under the contract between Volvo and Jensen Motors Ltd.

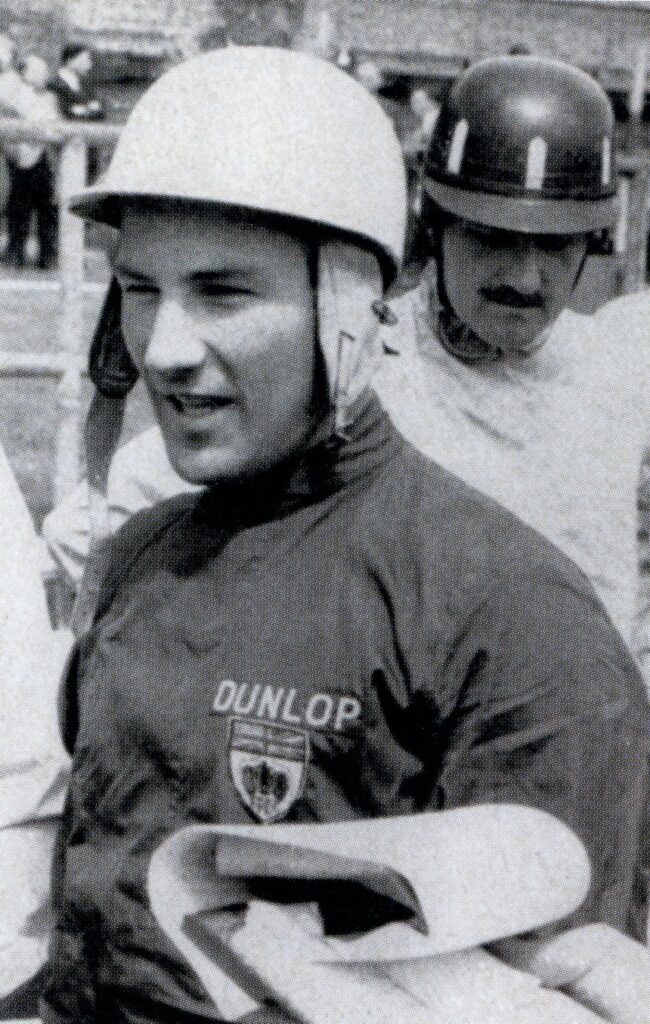

Stirling Moss tries the P958

Suddenly, a request came from Gunnar Engellau that someone in the subject a particularly qualified person should be given the opportunity to test drive the sports car and give his judgment. The assignment was forwarded to Gösta Vallin who contacted Richard Jensen, who in turn invited his brother Allan Jensen to come up with a proposal. As a result, the Duke of Richmond, better known as Freddie Richmond, was asked to test drive the new sports car. Allan pointed out that he would be addressed “Your Grace” in the letter, which Gösta Vallin sent, but the Duke ultimately declined. However, he pointed out that it was not out of disinterest but because of an impending stay abroad. Allan Jensen then came up with a new proposal: Stirling Moss, who responded positively and showed up at Allan Jensen’s house at the agreed time and was treated to a welcome drink, but drank only one ginger ale. Vallin remembers it particularly well because when Allan offered Moss a refill, he said: “Not very exciting”. Moss was very nimble when he got behind the wheel of the Italian prototype next to Gösta Vallin, it seemed that he liked the entry. He drove for less than half an hour and expressed neither delight nor disapproval and there was no ample conversation, so during the test drive Vallin switched to a conversation in interview form to get the feedback that Volvo had expected beforehand. What, then, did Mr. Moss think of the sports car? In a minutes from March 19, 1959, Gösta Vallin summarized the statements made by Moss and the conclusions that Volvo drew from experience. In conclusion, Moss was visibly impressed with the appearance and general design of the carriage. Moss especially liked the good visibility, the light steering and the well-fitting shape of the seat for him. Otherwise, the following reflections were made:

- Steering wheel: Moss suggested that the steering wheel should be lowered slightly, at least 10 mm, and that at the same time it should be moved forward longitudinally. However, Moss pointed out that among sports car enthusiasts, on the contrary, it was common to have the perception that they wanted the steering wheel close to the body and mentioned that most English sports cars were built with the steering wheel in a similar position as in the P958. Volvo had already foreseen and planned a lowering of the steering wheel, a conclusion that was reinforced by Moss. Moss also felt that a signal ring was preferable to a signal button because he felt it was of the utmost importance, especially on a fast sports car, that the driver did not need to release the steering wheel ring to be able to signal. In addition to this, Moss was fond of the profile of the steering wheel ring and its styling in general.

- Pedal placements: Moss suggested a minor change to the position of the accelerator pedal as well as a substantial change to the canvas to the left of the clutch pedal and that the light switch also came with it. In this way, the driver would be able to find substantial support for the left foot when driving bad roads. Volvo would also seek to meet this need

- Handbrake: Moss felt it was important on a car of this type that the hand brake should be made up of a lever in the floor. Its location was a given for Moss, namely at the side of the chair on the left side. On the prototype, the lever sat in the said place but was unusable due to the combined armrest with glove compartment placed on the door. Volvo’s specification had stipulated that a handbrake of the type drawbar under the dashboard would be used to be able to maintain armrests and glove compartments, but this changed Volvo before the production of series cars started.

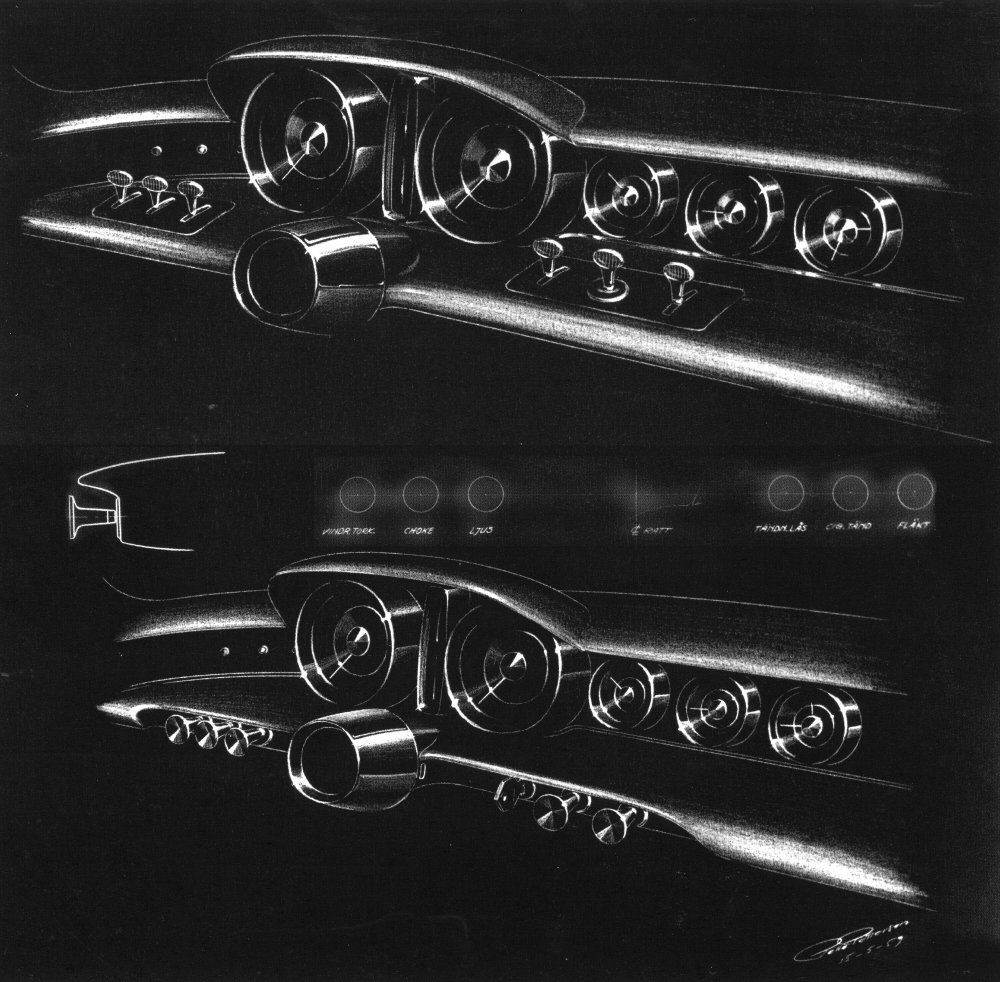

- Controls: Vallin noted after a fairly detailed discussion that Moss was of the following opinion regarding essential controls: “The ignition key and choke button shall be located on either side of the steering wheel. These two, along with the light switch and windshield wiper coupler, should be at a steering wheel radius distance or more from the steering wheel center. Cigar lighters should be placed closest to the passenger. Heating controls preferably in the middle of the carriage so that the passenger can possibly use them and the other buttons do not require much care in the placement.” Volvo would take these views into account to the fullest extent possible in the design.

If Moss had been allowed to decide, the gear lever would have ended up a little further back, but that didn’t happen. Something that Volvo listened to, however, was Moss’ demand for “a glove compartment easily accessible to the driver and that at least accommodated a map, sunglasses and chocolate bars”. This resulted in the two front storage compartments, one on each side. Then Moss left comments on the location of the rear view mirror, which, however, turned out to be a bit problematic. However you moved the mirror, it obscured essential parts, either of the view of the right front fender or either a very large field of view. However, this could be improved to some extent by moving the mirror a little further forward in the car but still in close proximity to the old position. Nor did Moss like that the rear view mirror was chrome-plated as it caused unpleasant reflexes. This, too, was taken into account by Volvo. In conclusion, Mr. Stirling Moss expressed his great delight that Volvo planned to have seat belts as standard on the sports car. Six months later, someone in Mr. Moss’ organisation sent a bill of £900. Vallin wrote back and announced that he would be “very pleased” to send the amount as soon as Moss confirmed in writing that he had actually driven the car. However, no money was ever paid out.

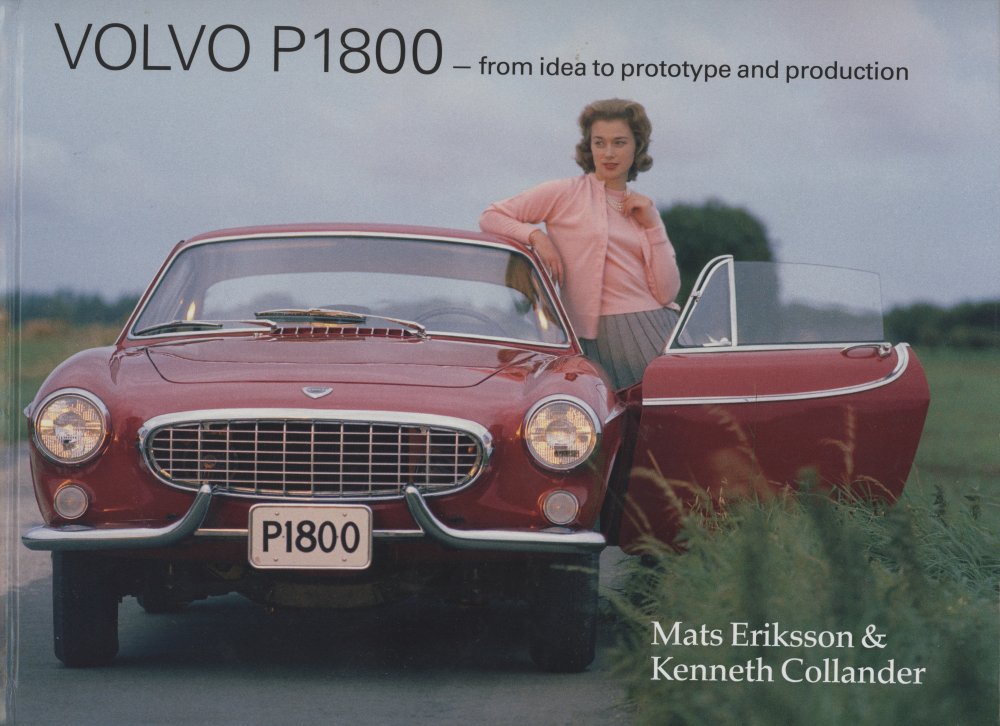

Volvo new sports car go public

On April 28, 1959, T.G. Andersson informed his main contact at Pressed Steel, Mr.D.D. Hobday, that Volvo had no longer managed to keep plans for the new sports car secret and that it had therefore decided to publish the new product as early as Sunday, May 3. It is said to have been the case that in connection with a secret tour, Gunnar Engellau had had the Italian sports car prototypes shown to a select few Swedish motor journalists, in order to collect feedback on the new car from them a little in advance. Among these journalists was Lennart Öjesten, who at this time was a reporter at the newspaper Motor. A confidential agreement had been established, meaning that these reporters were under a duty of confidentiality. Shortly afterwards, Öjesten is said to have contacted Engellau and announced that he would quit his employment at Motor and instead start working at the newspaper Expressen. Because of this, Öjesten considered that the agreement on professional secrecy no longer applied and that he intended to present the news shortly in Expressen. This is said to have given Engellau some trouble and Volvo quickly decided to publish the news about the new sports car before Expressen had time to go out with the news and get the publicity.

In connection with this, Volvo sent out the following internal memo to its employees about what was about to happen:

May be published no earlier than Sunday, May 3, 1959

Volvo has designed and will start manufacturing a coupe-type sports car. It will be equipped with Volvo’s sports engine and four-speed box. The car will be two-seater with two extra seats in the space behind the driver’s seat. The dimensions will be: length 440 cm, width 170 cm, height 129 about, wheelbase 245 cm and track width 131 cm. The car will be 100% a Volvo product, based on Volvo’s own designs, but the tools for the body will be manufactured in England. The production of the body will take place at Pressed Steel, England’s largest company in the industry. The assembly will also take place in England. The reason why these works are placed abroad is that all available capacity in this country in these areas is utilized for Volvo’s current manufacturing program. By the end of the year, Volvo expects to be able to show a copy of the new sports car to the press and audience. It is expected to enter production at the end of 1960 and will be sold through Volvo’s organizations in Sweden and abroad. The price is yet to be determined, but the sports car will be significantly more expensive than Volvo’s current passenger cars.

Along with this brief information, Volvo released photos of the second Frua-built prototype, the P958-X2. The pictures attracted a lot of attention. What had happened to Volvo? The company known for its robust family cars showed off a sports coupe. Many wanted to buy right away, but Volvo announced that production would start on a smaller scale at the end of 1960. It would be another eight months before the sports car would appear in reality.

Final assembly at Jensen Motors Ltd

Jensen Motors was responsible for producing other drawings for the included parts for the sports car and at Jensen’s reigned Eric Neale over the design office. He was an experienced man when it came to quickly developing a product and he had a very large network of contacts among possible subcontractors and spared no effort in presenting them and their company to Gösta Vallin. It was a joy when Vallin understood their great interest in joining the project, among other things because Volvo had a good reputation for paying punctually.

There were several difficulties in getting started at Jensen. Mr. Neale certainly had experience, which, however, his designers seemed to lack. He wanted to decide everything in detail and his co-workers were forced to redo the drawings as soon as he reviewed the drawings. The fact that he himself ruled over his subcontractors with frequent visits and constant telephone contacts made the management of the work inefficient, which in turn made the work considerably more difficult for Vallin. No protocols were taken and any attempt to get a thorough review of the situation was devastated by Mr. Neale’s constant interruptions for telephone contacts and uncontracted supplier visits. At the bottom was solid know-how and a determined desire to get the work done to Volvo’s satisfaction, but a lack of organized follow-up meant that the time frame risked falling apart.

Instead, Jensen suddenly hired a man to oversee the Volvo project. He had no experience in the manufacture of cars and his efforts consisted of being cumbersome in most contexts. To take one example: Vallin had made it clear from the start that Volvo needed to test the first prototype car at the MIRA (Motor Industry Research Association) Proving Ground, which was a test track common to the English automotive industry outside Coventry. Volvo could not get permission to drive on the track, so it was instead agreed that Jensen Motors would be responsible for this. Suddenly, this newcomer got the idea that it was going to be expensive and called a meeting with Richard and Allan Jensen, Cfo Stephenson and Gösta Vallin, explaining that Jensen couldn’t possibly smuggle a foreign car into MIRA. Vallin pointed out that Volvo already had Amazons at MIRA through a brake supplier but that Volvo needed its own garage for the sports car tests for service and measurements and that Volvo could not understand Jensen’s objections. Vallin thought Pressed Steel could help Volvo, but before Vallin asked them, he took a one-on-one conversation with Stephenson. He understood Vallin’s dissatisfaction and the next day he came again and the matter was clear but only one obstacle existed, namely that MIRA required a Jensen employee to be at MIRA for the time Volvo disposed of the test track and the cost to him should be charged to Volvo.

During the first part of 1959, Vallin did not have his own office but kept his binders on a windowsill in his hotel room in Droitwich. When Gunnar Engellau came to visit and asked what Vallin thought he needed to improve work opportunities, the answer was that an office with its own telephone was needed, partly to tackle Eric Neale in his own environment and partly to get somewhere to work for the Volvo engineers, who were already then predicted to be needed to row the project home on time and in a usable condition. Engellau took this home to Gothenburg, including Åke Zetterström on the planning. Discussions were then held between Gunnar Engellau, T.G. Andersson and Tord Lidmalm and towards the end of November 1959 it was decided that … Volvo would have some kind of office at or near Jensen Motors with opportunities for writing assistance as well as some male person as a coordinator could hold in the upcoming needs of contact operations. The wish from Vallin was fulfilled immediately and the same was true for Volvo’s control operations, which also included lockable spaces for tools, etc. It is worth mentioning that Jensen Motors was controlled strictly hierarchically. Neither Richard nor Allan Jensen made any visit to or follow-up to the business. Although they themselves once started by screwing up their sports cars in the garage, it never occurred that they “came down to the floor” in production either.

The work was intense and Vallin pulled a heavy load to move the sports car project forward. Vallin recalls that during the summer of 1959 he could not take a regular holiday, instead taking his wife and daughter to Droitwich while Vallin’s mother took care of the son. In the time spanning from the autumn of 1958 and onwards, Vallin had only gotten to know one person more closely on the private plane, it was an 83-year-old who had three industries running and who, according to Richard Jensen, suffered from “notorious hospitality”. Through him, Vallin gained some experiences well in line with what one read in P.G. Wodehouse’s books. Vallin’s wife, who found it easy to make social contacts, quickly established contact with a number of families with whom Vallins then had contact and visited for many years. The English families also came over and visited Sweden. From that time on, Vallin gained good social contacts in parallel with all the hard work. During the summer of 1959, Tord Lidmalm came over to visit and discussed the situation with Vallin and the Jensen brothers, who assured that they would row the project home on time. For some reason, they had got the idea that Lidmalm would think it would be fun to ride in a Rolls-Royce, it was arranged but Lidmalm did not want to drive the car. Instead, it was Vallin who had the great experience of driving the Rolls for an hour on small roads in Worcestershire.

Extensive planning work was underway throughout 1959 and by December Jensen Motors found that it had the capacity to store 120 bodies “body in white” as well as 150 finished sports cars under cover. This was sized at a production rate of 100 sports cars per week to begin with, but with the possibility of expanding to 300 cars. At the end of 1959, it was time for Jensen Motors to complete the layout of the assembly line at the factory and Jensen Motors also faced challenges when it came to the complex storage of components and spare parts for the sports car as most of the components came from Volvo or Jensen’s subcontractors. These issues concerned, for example, the engine, rear axle and suspensions. Initially, it was planned to store sets of complete component kits for approximately three weeks of production to be adjacent to the assembly line at Jensen Motors. On 17 and 21 October 1959 a variety of components were transported by air freight to West Bromwich and on 28 October two engines (Nos. 29 and 32) with m/s Suecia were sent to London.

At a meeting of Jensen Motors Ltd. in the boardroom at Kelvin Way on December 3, 1959, Jensen and Volvo agreed on the following working model regarding design changes: 1) Jensen proposes changes to the design department of passenger car construction at Volvo; 2) Volvo approves and sends a “Modification Note” as well as updated drawing/specification with the necessary references to both Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel; 3) Jensen documents the change and notifies Volvo from which chassis number the change is inserted; 4) The same procedure applies to modifications introduced by Jensen Motors suppliers, who must accept all changes.

Paint, trim and customs matters

Gert Ganemyr worked in the body construction department under Raymond Eknor and in 1959 he was involved in the sports car project. Ganemyr was present when Gösta Vallin set up the office at Jensen Motors’ factory in West Bromwich. Ganemyr recounts how he was carrying three suitcases filled with drawings and parts of a gear box traveled by plane to London, then on by train to Birmingham to finally get to Dudley where he lived. Ganemyr’s task was to compile so-called detail lists with specific detail numbers (now called these part numbers) to create the conditions for all details to be checked and available during the assembly of the sports car. The very first detail list for the sports car was created based on a regular detail list for Amazon, which was then modified into the sports car. The work on the detail lists became very extensive and required the involvement of another person, a man named Göran Berggren who became Ganemyr’s colleague to complete this work. Gert Ganemyr spent a lot of time in England during 1959–61. The first concrete task was actually to go home to Pelle Petterson and in his basement in Gothenburg hand over drawings of hubcaps and wheels from Volvo for further design by Petterson. Ganemyr confirms the picture that several people involved in the sports car project reproduce, namely that the project was run as a side project at Volvo in parallel with all the other regular work that was going on.

Volvo and Jensen Motors agreed early on that the car would be produced in three different colors and three upholstery combinations. Jensen was also positive about developing metallic paints, which later resulted in a grey metallic variant. In December 1959, Volvo began the preparation of handbooks and service manuals for the sports car, for this work Lennart Wrang was responsible. The basis for the manuals was planned to be ready in early June 1960 in order to be completed before the start of production. The work carried out in the spring of 1960 included the collection of technical documentation, manuscripts, drawing and retouching work for about five weeks. Since the English-built prototypes were listed in various tests and testing programs, only three possible sports cars were available for this very purpose. As detailed documentation about the sports car was required for the manuals, one of the Italian prototypes for dismantling and study in the spring of 1960 therefore needed to be accessed. This needed to be carefully coordinated with Åke Larborn’s men at the engine laboratory who were responsible for test drives with these cars during the same period. In March 1960, about twenty photographs were taken for the P1800’s various manuals.

Another issue that Volvo was forced to devote energy and effort to in the spring of 1959 was contacts with the British customs authorities, Customs & Excise in London, which was most closely matched by the Swedish General Customs Board. By sending engines and gearboxes from Volvo’s factories in Sweden to England for installation in the sports car, Volvo risked being forced to pay customs duty. In June, however, Customs & Excise was able to confirm that Volvo is exempt from customs duties provided that these details are then exported from England after importation. However, as a condition of duty-free, Customs & Excise required Volvo to provide a guarantee, through an insurance company or bank in England, in an amount that would constitute the duty on Jensen’s foreign material lying around at any time. This sum was then calculated at a production rate of about 100 cars per week, whereby the duty on this material would be about SEK 300,000 and the bank guarantee of about SEK 3,000.