Bringing home the car

The Saint the best salesman

The 1962 Stockholm motor show

Volvo plans for more news

Colours and trim

Instrumentation

A more powerful engine

New colours

The start of RHD production

Quality questions, modifications and financial matters

The “Whisky cars”

Beginning of the end for the AB Volvo and Jensen Motor ltd cooperation

AB Volvo breaks off the Jensen contract but carries on with Pressed steel Co ltd

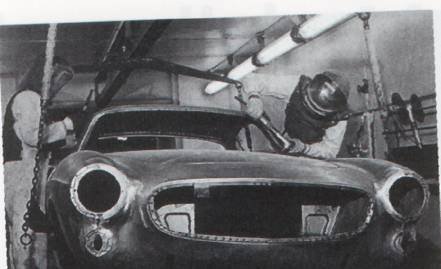

From West Bromwich to Lundby

The transfer of the production

The first cars are built at Lundby

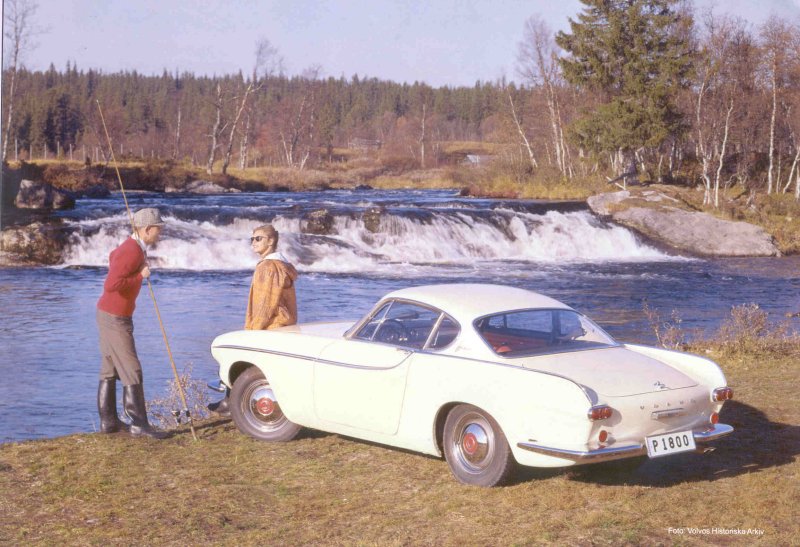

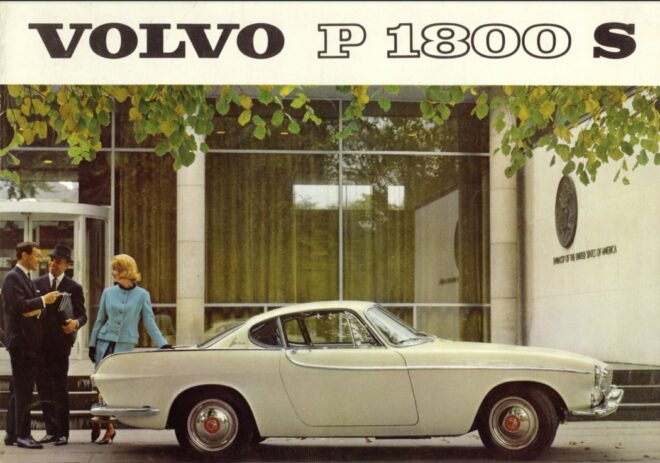

The Swedish built Volvo P1800S is launched

Bringing home the car

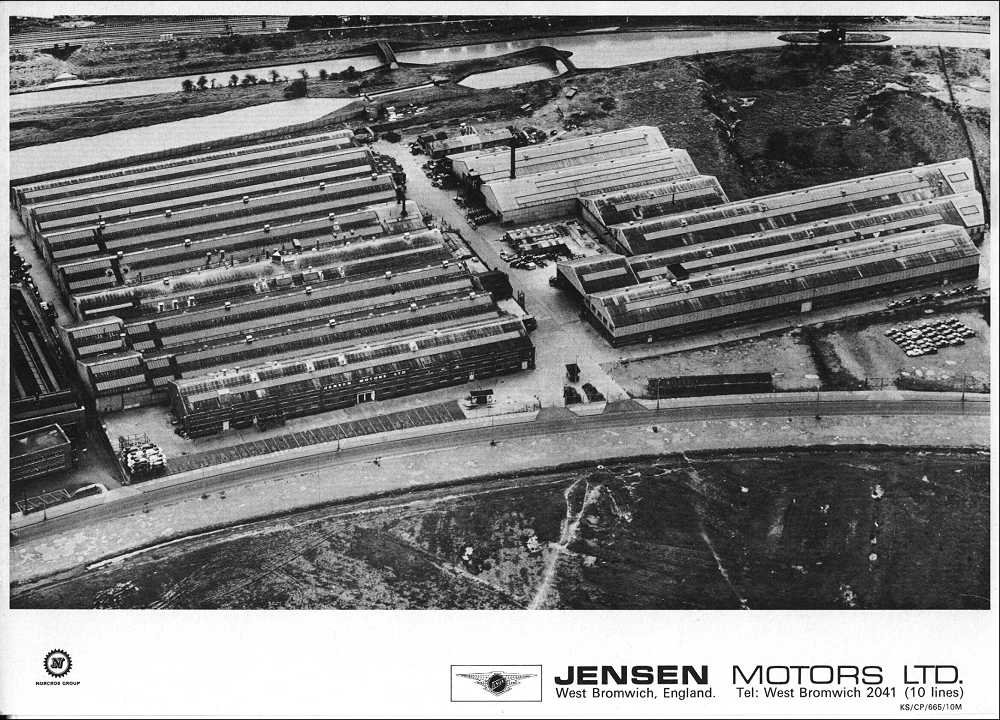

As early as August 1961, Volvo raised the question of bringing production home to Sweden. Director Svante Simonsson convened a small group of representatives from design, purchasing, production and planning, consisting of Simonsson himself as well as Tord Lidmalm, Nils Redvall, Bengt Darnfors, Åke Zetterström and Bengt Albrektsson. After pointing out the confidential nature of the case, Simonsson continued to inform this working group that since the experience of cooperation with Jensen Motors so far had been so poor, there was well-founded reason to plan for a possible repatriation of production. In the preparatory work, Bengt Albrektsson was given the task of analyzing §6 of the contract with Jensen, in order to clarify Volvo’s right of cancellation after 5000 cars had been manufactured and that notice of this would be given to Jensen within one month from the delivery of the 2000th car

Simonsson pointed out that no repatriation of production could take place until increased capacity was available at Volvo. This could not be realized until the end of 1962 when the new paint shop was planned to be completed to relieve the “Forester”. Through the D-factory’s new assembly hall in Lundby, the necessary assembly capacity should also be available for the P1800 in the autumn of 1962, provided that the track change between passenger cars was carried out no later than in connection with the holiday and that the number of Volvo PV and Duett was limited. Space might be required outside the D-factory for some preliminary work. Sometime in the late autumn of 1961, chassis number 2000 could be expected to have been delivered and, based on previous investigations, Volvo should thus terminate the agreement with Jensen in such a way that production continued into the fourth quarter of 1962 where Volvo then took over. It was estimated that it would take about four weeks to get up to a production of 100 cars per week. Åke Zetterström was instructed to draw up a start-up plan for the takeover based on the continued purchase of complete body-in-white bodies from Pressed Steel. This work was, of course, strictly confidential so that no information would leak to Jensen Motors prematurely and jeopardize and further complicate the already hard-pressed relations with Jensen’s, which would directly risk damaging continued production growth and increased deliveries that Volvo so badly needed.

Under Zetterström’s leadership, contact persons from the various departments were appointed to process the issues and to their help they had, among other things, a dismantled P1800 car from which all Jensen details were marked as viewing material for the purchasing department. The initial work aimed to clarify procurement times and tool costs as far as possible. It was estimated that approximately 4750 hours would be required for the preparation of drawings and necessary redesigns of the chassis and body, which were focused on Jensen’s manufactured details. The purchasing department estimated at an early stage that the schedule for the upcoming process, which included the completion of drawing documents, inquiries to suppliers and their response to the purchase and the delivery of details, would amount to approximately 11 months. This would mean that production of the Swedish-made P1800 would start on 1 April 1963. The total tool cost was estimated at approximately SEK 1.5 million, while Jensen spent approximately SEK 2.5 million. The difference was attributable to the cost of tools for bumper, dashboard, instrument and lock, grille, grille and steering wheel. Volvo’s intention was that these details would continue to be purchased from current manufacturers.

Bengt Albrektsson’s work to analyze §6 of Volvo’s contract with Jensen regarding Volvo’s right of cancellation resulted in that since the 2000th car was expected to leave Jensen around December 5, Volvo would own the respite until the end of the year to take up the contract discussion with Jensen Motors. Under the contract, Jensen would then continue production for seven months at the average rate they had achieved in the past four weeks, which was estimated at about 110 car. They had the right to break the contract after 5000 car were manufactured and in that case notification of this would be given to Jensen within one month of the 2000th car being delivered. From that point on, Jensen would continue production for seven months. The investigation into the repatriation of the P1800 production then continued during 1962

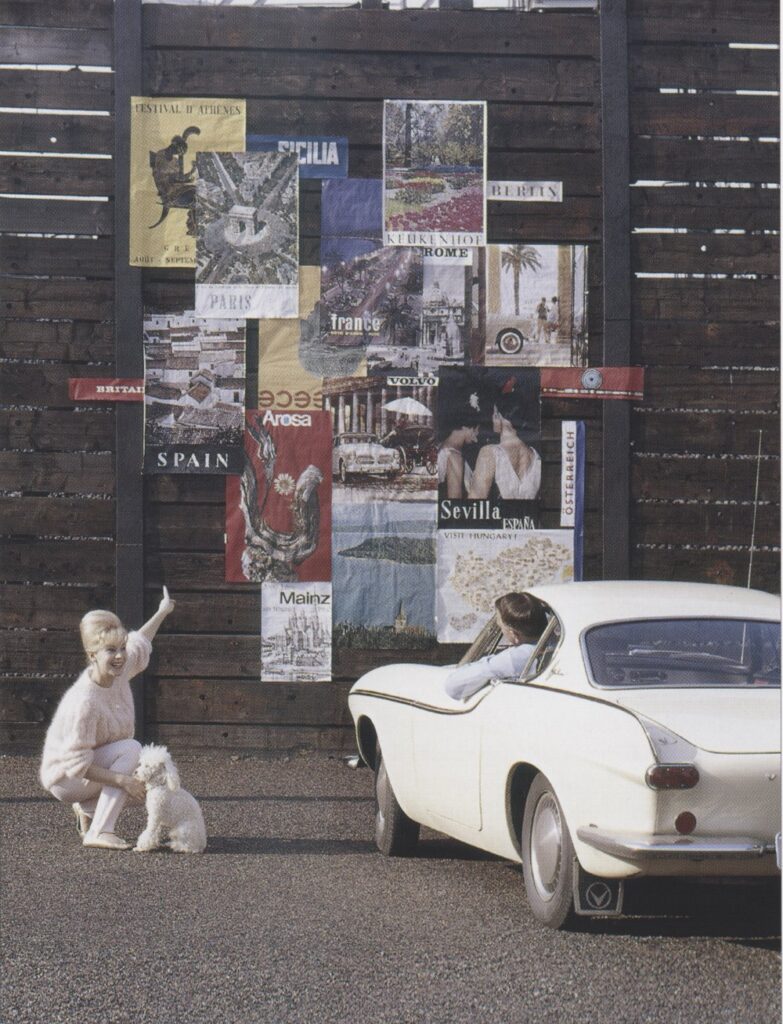

The Saint the best salesman

Volvo’s P1800 sports car probably wouldn’t have become as famous as it is today, had it not been for the Saint, (“The Saint”, aka Simon Templar) played by Sir Roger Moore. The saint ran his P1800 for over 100 episodes in the famous TV series introduced during 1962. When Sir Roger Moore played Simon Templar once a week, the entire Western world could see the snobbish detective being whizzed along in his white Volvo P1800 with a red interior. Often it is enough to say “The saint’s car” when you as a P1800 enthusiast want to describe your car, because then most people know which car you mean.

Volvo had great help with the marketing and advertising of the Volvo P1800, for better advertising than with the Saint, Volvo could not ask for. Leif Olsson at Volvo’s foreign control remembers a fun event when suddenly one day some unknown men appeared who had contacted Helge Andersson and who then came out in the assembly plant at Jensen Motors and asked if it was possible to “borrow” a dashboard with steering wheel and steering wheel rod as well as some parts of the coupe and interior for the P1800. Of course they got it, after they told them they were going to make a movie. It was only after some time that Leif and his colleagues found out that the anonymous visitors had come from a production company in London and collaborated with the film studio that built up the scenes for the recordings of the TV series “The Saint”. By the mid-1960s, Leslie Charteri’s novel character had been sold to 79 different countries, breaking the Cartwright brothers’ record with 390 million TV viewers.

Exactly how the P1800 came into question as the Saint’s car we are not likely to know, but one man who played an important role in this context was Mr. Charles Singer at Lex Motors Group in London. According to Helge Castell, it was Charles Singer who ensured that the P1800 became Simon Templar’s car in the famous TV series. Originally, it was intended that Roger Moore would drive an Aston Martin, which was also in the Lex Motors stable, subsequently changed to the new Jaguar E-type. Volvo realized the value of this marketing opportunity and quickly stood ready with its new sports car and in the end it became the Volvo P1800, and the rest is automotive history.

Exactly how the P1800 came into question as the Saint’s car we are not likely to know, but one man who played an important role in this context was Mr. Charles Singer at Lex Motors Group in London. According to Helge Castell, it was Charles Singer who ensured that the P1800 became Simon Templar’s car in the famous TV series. Originally, it was intended that Roger Moore would drive an Aston Martin, which was also in the Lex Motors stable, subsequently changed to the new Jaguar E-type. Volvo realized the value of this marketing opportunity and quickly stood ready with its new sports car and in the end it became the Volvo P1800, and the rest is automotive history.

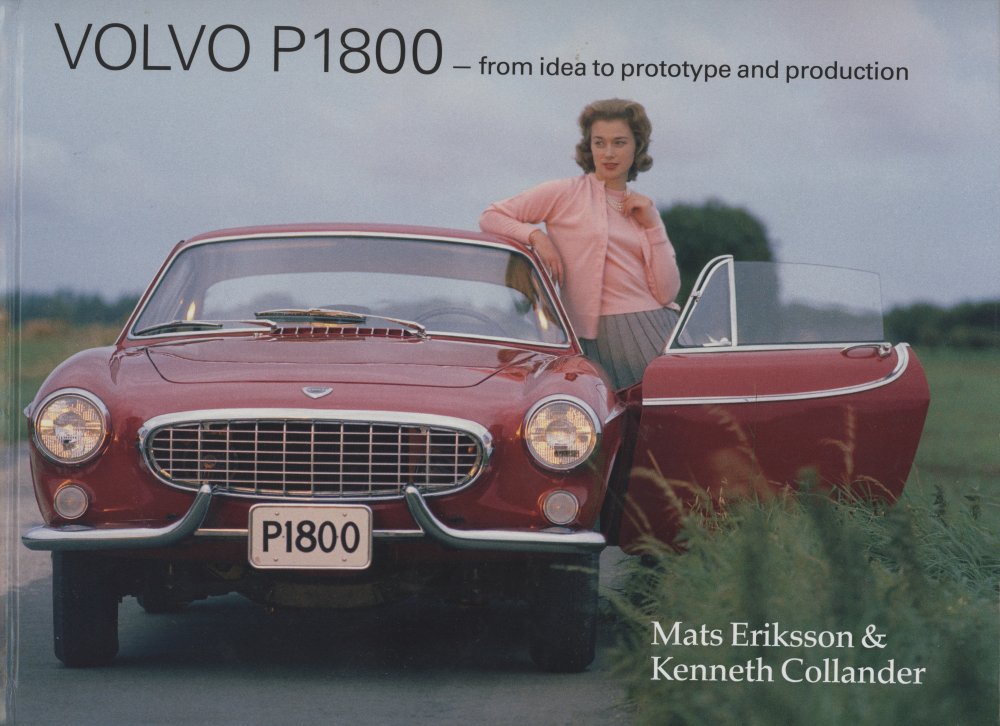

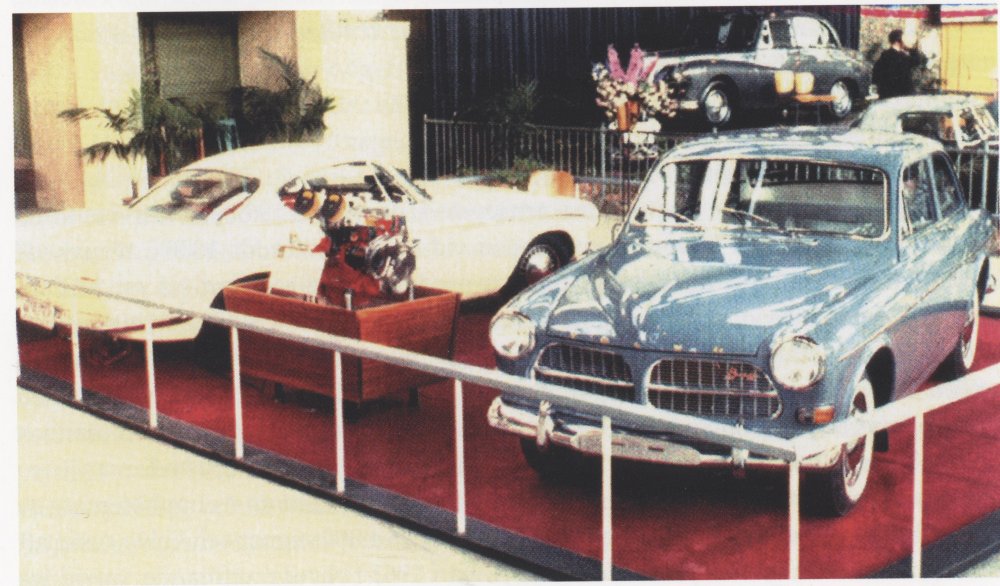

The 1962 Stockholm Motor Show

At the Stockholm Motor Show in the spring of 1962, Volvo exhibited a red and a grey P1800. Otherwise, they showed Amazon estates (mist green and fallow brown), Amazon (mist green and slate blue two-door variant and a black and a fallow brown four-door variant), PV 544 (light grey, slate blue and red) and a slate blue Duet.

Volvo’s press material, which was presented in connection with the salon, reported, among other things, that the P1800 recently received a gold medal at a major exhibition in Sacramento, California. There was an annual trade and industrial fair and gold medals for “design and marketability of new goods on display”. One of these medals awarded in 1961 went to the P1800 and was handed over by the head of the fair at the Stockholm Motor Show to Volvo’s representative in California, Sam C. Mitchell. On February 15, 1962, the medal, together with another 32 similar medals for Swedish goods, was on site in NK’s exhibition hall in Stockholm. The party items, the goods, were also gathered for an exhibition. The exhibition was opened with speeches by the board member of the Swedish Chamber of Commerce for the United States, P.J. Coyet, and honorary chairman of the same chamber of commerce, Eric Hallbeck. Hallbeck emphasized, among other things, that trade between Sweden and the west coast of the United States has increased seven-fold since 1948 and in 1960 goods were sold for about $ 20 million in both directions. After the speeches, Mr. John A. Birch, the Trade Council of the U.S. Embassy, presented the medals to representatives of the various manufacturers.

In a vote in a Swedish motor magazine, the P1800 was chosen as “the most beautiful car of the year”. Volvo particularly wanted to highlight that two adults and two children could comfortably fit in the P1800, which for a sports car had an unusually large luggage compartment and where the driver sat excellently in his adjustable seat, which was a definite plus on long day stages at high speed. In connection with this attention, Volvo was also proud to announce that the racing driver and double (1959 and 1960) world champion, Jack Brabham, had test-driven the P1800 during a week-long tour in Austria. He was particularly concerned with the good road holding characteristics and the good cooling and excellent braking effect of the disc brakes without oblique traction.

Volvo plans for more news

During 1961–63, there was a constant development and improvement work regarding the P1800. Some of the changes were more extensive than others.

Colours and trim

The interior design for the 1961 model year was initially offered in two different designs: red vinyl (301) and white vinyl (302), but in December of the same year Gunnar Engellau, Svante Simonsson, Per Eriksson and Tor Berthelius decided jointly that leather upholstery should replace previous vinyl upholstery. That meant the seating surfaces would be leather and the rest matching non-perforated vinyl. At the same time, it was established that two variants would be available in the case of leather upholstery, a red upholstery (color code 303) in cars of grey metallic color and a black upholstery (color code 306) in the red cars. As for the white cars, that question was left open. It was initially envisaged to introduce leather upholstery from 1 March 1962, but that time frame was later deemed unrealistic as the cost of scrapping already ordered and delivered vinyl materials would be too high. Instead, the transition was completed around March 26 at approximate chassis number 3800.

At the same time, it was clarified that the yellowish-white perforated roof cladding would be replaced by a grayish-white non-perforated cladding and the same was true of the sun visors. Furthermore, it was decided that textile and rubber mats should be replaced by a red cut textile carpet of high quality that would be used for all exterior varnishes. It was also decided that the Amazon’s then hubcap and ornamental ring would be used on the P1800 from chassis number 6001. The result was communicated to Jensen Motors Ltd., whose design department began working on the changes together with Volvo’s design and production managers. The estimated cost increase for the altered interior was £12.4 and included the new leather upholstery for the seats. The changes with new leather upholstery (codes 305 and 306) were intended primarily for the English and American markets. At the request of Volvo’s executive board, a cardboard box was also introduced at the rear edge of the trunk in 1962/63. Since the rear pads initially had to endure a lot of criticism, they were replaced with Dunlopillo pads in a sheet metal holder. In the vicinity of chassis number 3270, Volvo delivered a number of these red cars with black interior. This was marked with chalk inside the ceiling of these cars with the text “special trim”. The black interior additionally lacked silver trim and perforated holes on the side panels and front seats lacked the coarsely perforated vinyl fabric in the middle part and on the cushions in the back seat. Famous red cars with this black interior are chassis numbers 3270–3273.

Instrumentation

Questions about improved styling on the instruments were raised early on, not least by Gunnar Engellau himself. The desired changes discussed with supplier Smiths were, above all, an angry red color for the warning bar on the tachometer and reversed colors for water and oil on the temperature gauge. In addition, they wanted to make the 50 km marking on the speedometer clearer with a clear red marking, the same applied to the fuel gauge where a red field would be introduced for empty tank. The oil pressure gauge was provided with better lighting and at the clock was introduced illumination of hands, longer and wider hour hands and longer minute hands on later cars. At the beginning of 1962, cooperation with Lucas was also initiated with the aim of developing new front and rear lamps with two-color glass with yellow glass on the turn signal lamps, as this was required by the legislation of several of Volvo’s export countries. However, requests for parking lights remained and this would be white. As different specifications for areas on each yellow and white field existed for different countries, Volvo faced an intractable situation. Lucas worked on the issue and got to the point where the lamps could be approved in all countries except Switzerland for introduction in 1963.

Otherwise, it was decided to change the design of the hubcap. As early as December 1961, both Engellau and Simonsson announced a transition to the Amazon capsule. On the one hand, the fastening was not reassuring for the old capsules, and on the other hand, they impaired the cooling of the brakes and likewise its design had met with criticism as they did not appeal to customers in terms of appearance. As a result, a decision was made to introduce the new Amazon capsule in 1963.

A more powerful engine

In 1962, Tord Lidmalm’s design department at Volvo developed a new engine that would provide 109 hp through a minor compression increase. The power curve would be better and 97-octane gasoline would be sufficient. It was decided that any introduction of the new engine would be placed at the earliest at chassis number 6001 or at chassis number 10001.

New colours

In the spring of 1962, a number of different new paint colors were tested on P1800 cars. On February 23, 1962, an interesting exercise on this theme was conducted at the gas pump and laundry hall outside the Technical Workshop at Volvo in Gothenburg. On this occasion, Volvo had specially invited fourteen ladies and eighteen men to be part of a test panel to review a number of cars painted with test paints. After the review, a poll followed in which the test panel was allowed to pick out their two favorites.

The colours that were up for judgement were Ice blue, Tin grey, Moss green, Cypress green, Dark blue, Copper brown and Light blue. Volvo thougfht that only the the first four of these were suited for production. The jury picked out Ice blue and Tin grey as their favorites among these four, and of the other colours, the Copper brwon and Dark blue were the favorites. The cars used for this test were most likely 2367, 2368, 2369, 2370, 2371, 2372 and 2373, of which some still exists and are included in the Swedish Volvo 1800 Register on the internet

In February 1962, Volvo discussed the issue of metallic paints with Jensen Motors and, according to Mr. Clark and Mr. Richard Jensen, the additional cost would be mainly in the cost of paint and only a minor part in the cost of labor. Jensen pointed out the difficulties of improving metallic paints, although they were not at all concerned about this task. Volvo then let Jensen know that they wanted to change both the shade of the white color (69) and introduce a metallic variant on the grey color (71). In the spring of 1962, Volvo decided that the car colors from chassis number 6001 should be red, white and grey.

The start of RHD car production

The first right-hand drive prototype was probably ready as early as March 1961, after four pre-production cars were completed during June 1961. After lengthy discussions between Volvo and Jensen Motors regarding the agreement on the right-hand drive caes, Volvo placed a formal order for 496 right-hand drive cars in September 1961. The official series production of right-hand drive complete cars was initially planned to begin in June 1961, but it took until the autumn before it got underway in earnest.

During October/November, production continued at a leisurely pace and it was planned that the first eight cars could be assembled and ready at Jensen Motors Ltd. in mid-February 1962. Both Volvo and Jensen Motors had problems producing materials to complete the cars. Even Pressed Steel had initial problems with, among other things, the wrongly pressed dashboard and the wrong hollowing of the body. Production started between 12 and 16 February 1962 at an initial rate of 15 cars and then increased to 20 cars after a week. The first cars were completed in early March and judging by the delivery notes from Jensen Motors, chassis numbers 2701, 2702, 2909 and 2916 were right-hand drive. Chassis number 599, which was originally one of Volvo’s test cars, as well as 2711, 2714 and 2913 are also documented as right-hand drive from the beginning. By March 12, 25 right-hand drive cars had been fully reported and deliveries began around February 20. After chassis number 3001, which was reported on March 29, 1962, they were manufactured on the assembly line. The first 15 right-hand drive cars were produced with red leather upholstery on the seats (color code 303). On the advice of Gunnar Engellau, it was planned that these would be equipped with the new mats, but this was not done with and carpets had to be sent to Volvo Concessionaires.

Quality questions, modifications and financial matters

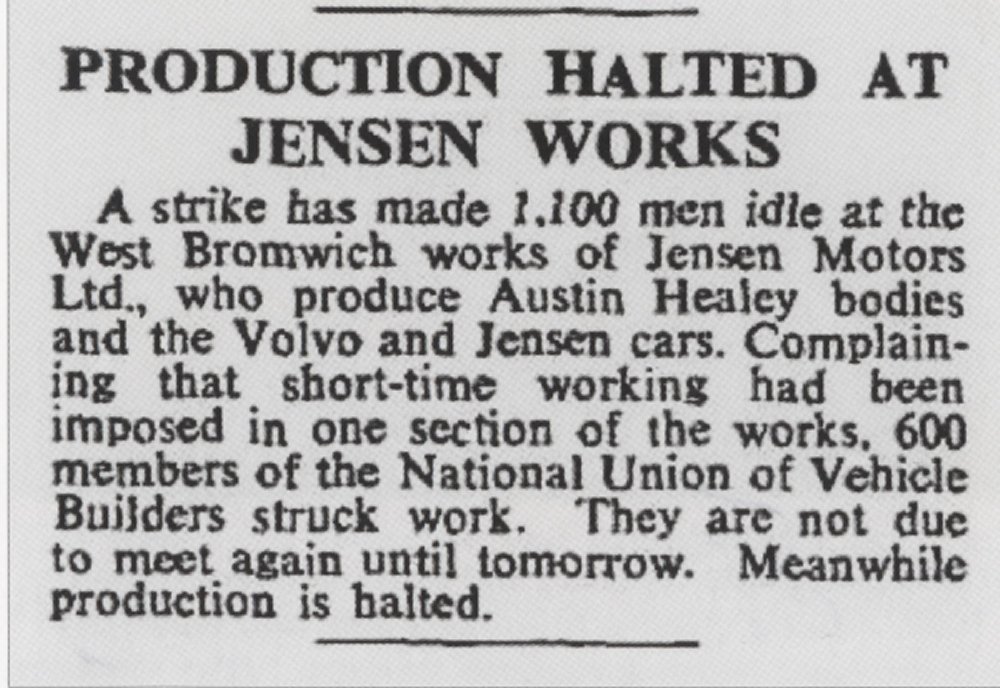

In early 1962, Volvo and Jensen Motors’ respective senior management continued to discuss outstanding financial issues regarding compensation to Jensen Motors. Jensen had already contacted his lawyers, Richards, Burlier and Co., and calculated the financial claim it intended to make against Volvo in the event of a breach of the contract. The requirement was £63500 for as yet un-produced cars and £115000 for other costs. During this time, there were problems in the English labour market and nationwide strikes were carried out, for example, on 5 February, which also affected Jensen Motors. At Smith Motor Accessories, there was also a separate masking operation, which meant that Jensen did not get enough instruments to fit in the sports car

From a document taken from the archives of Jensen Motors Ltd. from H.R. Clark of January 12, 1962 entitled “Reasons for Deterioration of Relationship between Volvo and Jensen Motors Ltd.” it appears that there were difficult circumstances at Jensen: The general attitude of all Volvo personnel, whether based at West Bromwich or in Sweden has been unfortunate in so far as it would appear that our own people have been regarded as not having the equivalent amount of technical or practical knowledge as their Swedish counterparts…This attitude was particularly apparent among the young Volvo inspectors based on West Bromwich whose uncompromising and aggressive attitude caused a great deal of bad feeling both on the shop floor and with senior management…The inflexible attitude of Volvo engineers in their discussions with opposite numbers at Jensen Motors virtually ruled out any opportunity of negotiation or compromise on any point at issue. Their general attitude was that they were always right and we were always wrong…From the outset of production Volvo have endeavored to prove by any means that Jensen Motors have been responsible for the poor showing of production figures…There has always prevailed among resident Volvo staff and visiting Volvo personnel from Sweden the attitude that we are a part of the Volvo organization, which leads them in their discussions with us to dictate, rather than request, alterations in systems or procedure. It was certainly not something that was needed in a situation where the production of the P1800 was threatened by both quality and quantity problems.

At the beginning of February, however, the atmosphere between Volvo and Jensen was relatively good and Tor Berthelius submitted a positive report from a meeting at Jensen Motors, which was eager to focus on forgetting the friction and dispute that had been. The situation was still to be regarded as unstable and the workload for Volvo’s representative for construction at Jensen Motors, Sven-Olof Andersson, was at this time too high, which is why a strengthening was discussed. On February 20, Volvo’s Svante Simonsson and Helge Andersson met with colleagues from Jensen Motors with Mr. Alan Jensen in the lead and a large number of open questions about payment of invoices were handled. Jensen’s maximum capacity was about 120 cars because, due to the availability of labor, it was not possible to increase the workforce but at the same time be able to guarantee income for the new employees. They had to maintain production with existing staff and overtime. However, Volvo clarified that it did not intend to change its wishes for the desired production rate, it would continue to be 150 cars per week and not 110 as previously announced.

When the cars with chassis number 2419 and 2421 were water tested in January 1962 the Volvo team at West Bromwich noted that the cars were still subjected to leaking in several places like the lower right corner of the windscreen, by the seat supports, around the c-pillar Volvo badge, quarter lights, lower edge of the left door, both sills, lower corners of the rear window, on the right part of the scuttle which caused water to drip on the passenger’s feet. This problems and a few other were brought up at meetings with both Pressed Steel and Jensen during February at which corrected actions were decided for to comprise both the body shell and the finished car. From Volvo Tor Berthelius, Sven Bengtsson and S.O Andersson were present. Points that required special attention were inside the upper part of the front wheel arch, the quarter lights, doors and boot lid rubber strips but not one single problem was neglected.

At a meeting in Linwood in February 1962 between representatives from Volvo, Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel, Pressed Steel lamented the additional costs it had caused Jensen and Volvo to date, which were mainly related to the labour-related problems in Linwood. Pressed Steel had reimbursed Volvo (and indirectly Jensen Motors) for part of the additional costs, but not to the level that Jensen in turn demanded of Volvo. This ultimately resulted in Volvo having to pay for the difference. Via Svante Simonsson, Volvo also tried to get Jensen Motors and Pressed Steel to negotiate separately on compensation levels for compensation around the body problem, but both Mr. Jensen and Mr. Clark of course refused to enter into any such reasoning because there was no agreement whatsoever between them, which was perfectly understandable since such an agreement would have been completely unrealistic and doomed to failure. At the same time, Jensen discovered that Pressed Steel had admitted to Volvo that it had never even been capable, nor would it be able to, produce 150 bodies a week. This naturally meant that Richard Jensen again contacted his lawyers because this meant that Jensen now had a strong reason to put forward as a basis for claims for compensation by Volvo, unless Volvo could show that Jensen also did not have the capacity to handle 150 bodies. Jensen Motors’ lawyers, however, advised Jensen’s to exercise caution on the matter at the risk of losing the Volvo deal and instead informally approach Volvo to hear if Volvo in turn could seek compensation from Pressed Steel. Production was now down to record lows, averaging 56 per week compared to the promised 150 cars.

The body quality was still below the standards required and agreed on in October 1961. The leading people from the Volvo department of production, quality and final inspection met with Pressed Steel in Linwood and the result was a decision for a completely new layout for the production premises and a new area for the Volvo body shell inspection. Pressed Steel also expanded their working hours, with overtime until 7,00 PM and two shifts including the nights, in order to produce body shells to an acceptable standard. Mr Thomson of Pressed Steel thought this was still going to be needed for several months to come. Volvo, on the other hand, had difficulties with getting enough control inspectors together to match those of Pressed Steel. To assist Pressed Steel with the transition to two-shift work, Bo Samuelsson from the control team at Jensen had to move to Linwood while waiting for more colleagues to arrive.

After this, Arne Hasselsjö went from West Bromwich to Linwood once a week in order to secure and optimize the transfer of experience and know-how between the Jensen and Pressed Steels control teams. Bernhard Hartshorn from Linwood did the same thing but in reverse. Pressed Steel once again went through the entire production process, correcting fails and making sure everything worked. Mr Earl of Pressed Steel said, in March 1962, that he now saw no obstacles whatsoever for Pressed Steel to produce body shells at a rate of 120-130 per week. What remained however, was the the unsolved workforce situation who continued their “go slow” action. By the beginning of April, the production was at a level of 15-18 bodies per day and the biggest technical problem had suddenly come to light; the system with mobile jigs along the line was now so worn that the bodies were not positioned exactly the same every time when worked on.

No major improvements were planned and Volvo started to realise that the required standard of the finish was never going to be achieved. Work for securing the situation started and at Jensen, Arne Hasselsjö worked together with the Jensen people on increasing the resources needed there to take care (adjustments, lead filling, soldering) of the bodies, naturally paid for by Volvo. Hasselsjö also looked for other paint shops in the vicinity that could take on parts of the painting. In Gothenburg in the so called D-plant, cars destined for Europe and US could be adjusted and painted after the summer vacation 1962.

The “Whisky cars”

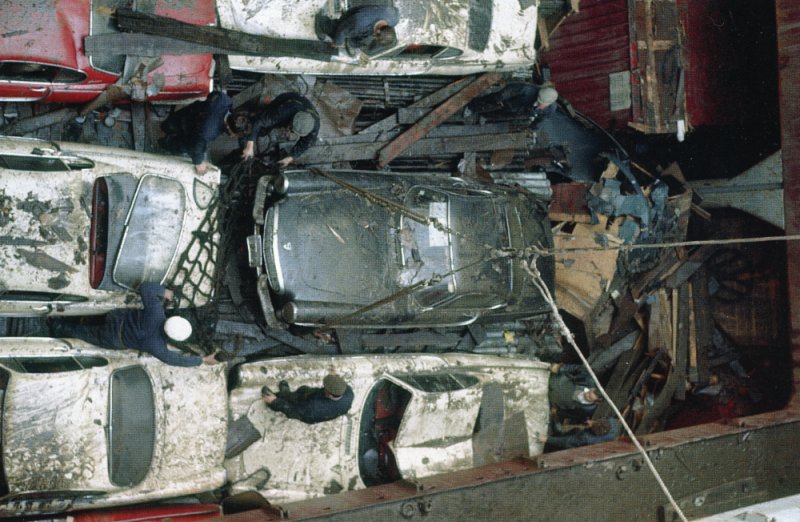

m/s Kassel. Loaded with valuables, collides on the River Thames

On March 29 1962 a dramatic incident occurred on the River Thames outside London. The Freighter m/s Kassel collided with the m/s Potaro. m/s Kassel was loaded with tubes from Germany and had just taken aboard additional cargo in the form of Scotch whisky and 29 Volvo P1800 cars, and was destined for Houston, Texas. At the impact m/s Kassel was ripped open at the bow, from the railing down to the keel, and the water poured into cargo holds number 1 where 18 of the cars were stored. The cars floated around crashing into each other and the roofs were heavily deformed.

In connection with this incident, Sven-Olof Andersson, based at Jensen, was ordered to come to London to inspect the damaged cars. Together with Lloyd’s the insurers, Andersson and his colleague Lars Grapengiesser, went to take a look. Grapengiesser was responsible for the shipping of cars from Jensen. Andersson recalls “We were met by a depressing but fascinating sight. The cars had been placed on the hold on a wooden floor on top of the German tubing under which the whisky was stored and the situation could have been worse but it was bad enough. m/s Kassel was bound for Texas bur shortly after the ship left the quay in London, it collided with another freighter and started to take in masses of salt water through the hole in the bow. The situation was so bad that the crew actually abandoned the ship in the middle of the river. The cars quickly named the “whisky cars” considering what was onboard”.

The ship was taken to a dry dock in Tilbury and kept under close guard because of the whisky. The cars had obviously gained an interesting smell from being soaked in Scotch and water. Andersson took some photos showing the demolished cars which was covered in mud. The people working in the dock nonchalantly walked around on the roofs of the cars and they were in general treated very carelessly during the recovery work. They were hoisted ashore with chains hooked directly in the wheel arches, causing some of the bodies to break. The aluminum panels on the dashboard corroded very quickly in the salty Thames water.

11 cars had not been damaged and were subsequently shipped to Houston on the first possible occasion whereas 18 damaged cars were shipped to Gothenburg and parked, covered by flannel sheets, in a closed section of the Lundby plant, where they couldn’t be spotted. Four of the cars were damaged beyond repair but the remaining 15 were sold at an internal auction. Carl Gunnar Söderberg and Hans Liljequist remember that it was mainly people from Volvo management that bought the cars. Hans Liljequist, a test driver at Volvo for 42 years was involved in driving the first Jensen-built cars that came to Sweden. As expected, the best cars were sold first at the Volvo auction and the worst ones were the last to go. They all went cheaply, the price ranged between 4,000 to 6,000 Crowns (dealer price 21,000). About four cars per week were sold and the fewer the remaining cars, the higher the bids. It had become apparent that the cars really did not need so much attention as it had seemed which of course affected the price. The last to be sold, however were really badly damaged with the roofs caved in and a lot of big dents all over the bodies. The buyers had to promise Volvo not to re-sell the cars to “outsiders” until at least three years later. Volvo didn’t want the cars to get to the market because they would most likely start to rust much quicker than the ordinary production cars and thus create a reputation for bad quality. But promises are made only to be broken, so several buyers fixed their cars and sold them off more or less immediately, at a much higher price, making really good deals and Volvo couldn’t do anything formal about that.

Are there any cars still around today that were among the “whisky cars” ? From the Volvo archives, the information has been found that the following cars were involved: 3226, 3227, 3233, 3239, 3241, 3242, 3252, 3260, 3261, 3262, 3263, 3266, 3267, 3274, 3278, 3283, 3284, and 3285

Bengt Lidmalm. the son of Tord Lidmalm and an ex Volvo man himself was one of the lucky buyers o a whisky car: “Oh, what a beautiful car the P1800 was. During the summer of 1961, I was privileged to drive around in a silver-coloured car, thanks to my father who used it as his personal transport. Gunnar Engellau had one in gold an Svante Simonsson a bronze car. This was just after I had passed my exam and my fellow students thought it was a gift from my father! Sadly not. But to be able to use the car was also a kind of a gift and that someone else took care of the fuel costs.

Alas, this was not to last but during the spring of 1962 a fantastic opportunity came by 18 British built cars had been dragged out of the River Thames after a collision involving the freight ship they were on and another ship. I remember that my father was involved in the British production one way or the other and spent a lot of time there during these years. He was not too happy with the situation and the production was later transferred to Sweden. Nevertheless, the cars were salvaged and we, who knew the British built Volvos, knew that they leaked but but these cars had at least been leaking less than the ship carrying them. The floated in the cargo hold and bumped into each other and everything that surrounded them. They were hoisted abroad very brutally which caused further damage to them. Most cars had bashed in roofs and bent wings. They were brought to Gothenburg and put aside at the plant in order to be sold on offer. Having driven a brand new and shiny P1800 before, you were a bit spoild but all of a sudden, here was a chance to to acquire a P1800 at a reasonable cost although a bit dented and smelling from dirt. Stories about the cars circulated. One of them was that all the copper in the electric wiring had already corroded away, and so had all the aluminum parts. And the rust. I opened the doors of one of the cars and my shoes got we from the water that splashed out. Apparently water leaked into the cars, but not out. I put bids on two red cars, 5,500 Crowns each, and got them at that price.

I kept one and gave the other to my uncle. dad’s brother. I had to promise not to sell the cars for three years. But the cars were not so bad as reputed and I learnt a lot from taking my car apart. The myth goes that some of the buyers only made and oil change and used the car again, but that was only a myth. Everything had to be taken down. I hosed the car down with fresh water, let it dry and then disassembled it completely. When I opened the engine oil plug, water poured out of the engine and after the water came the oil. This had been high up in the engine which saved the liners and the cylinder head and valve mechanism. The SU carburetors were badly corroded but a couple of days in a bucket of Kerosene made them work again after a bit of adjusting. All ball and roller bearings were corroded. The front suspension, the gear box and the rear axle had to be taken apart and all bearings replaced. The Smiths instruments with all their delicate parts were cleaned and I got them all to work again, except for the oil and water temperature gauges. These ‘roller blind dials’ never worked properly so I had to invest in new ones. The body and the subsequent painting I left with pros and to prevent the car from rusting, it was ML treated with Dinitrol rust-proofing. This worked except around the boot lid edge which started to corrode shortly afterwards. The electrical relays had to be replaced and the interior had also suffered from the swim. The Dunlopillo foam rubber couldn’t handle the salt water, making the seat position much lower, which in fact I needed.

Eventually the car was ready for the road, and after my military service, a friend of mine and myself took it to the French Riviera. It worked perfectly except that there was still some water in the brake system. After some inspired driving going downhill at St. Gotthard I suddenly lost the brakes. The pedal went to the floor due to the boiling brake fluid, or more correctly boiling water. The parking brake came to use on the next corner where a coach had just driven in a straight line and ended up with his front wheels hanging out and over the cliff and a number of pale tourists standing beside it. It was probably more luck tha skill that preventing me from sending both the bus and us into eternity. I had learned a bit about skidding on the Swedish winter roads and knew how to handle the car. From that point I was slow cruising in 2nd gear down to St. Gotthard. We had a great time and we also had a great car. Less fun to park though. Later, I got my racing driver license and went to race the car on several occasions. After four years I sold it to a man in the northern part of Sweden.

Beginning of the end for the AB Volvo and Jensen Motor ltd cooperation

During November 1962, the contacts became more intense and the number of trips across the North Sea for the Volvo management was legion. In the first week of November, Bengt Albrektsson and Helge Castell went to see their Mr. Garrett and to negotiate with Jensen Motors about the continuation of the production. Volvo’s standpoint was that it was possible to back off a little in order to get things going. Volvo thought that the only way to do this was for Jensen to install a special “rectification line” for the Volvo cars, for which Volvo was going to pay. It was accepted, and an agreement of additional work could be met. Volvo was also willing to pay £100,000 of the Jensen Motors demand, which was about Volvo failing to meet goal for delivered bodies, according to the contract of January 31st, 1959. Albrektsson pointed out the importance of getting the production under way again since a breach of contract would be much more expensive than running the operations. At this point, Darnfors and other Volvo’s representatives arrived and started to make plans for the forthcoming negotiations.

The next day a new meeting was held, involving Richard and Alan Jensen and Mr. Moore in the office of the Jensen solicitors who were represented by Mr. Wilson and Mr. Guiseppi. From Norcross, the company that owned Jensen, Mr Cunhill had arrived. The negotiations for a “rectification line” resulted in that Jensen was willing to do this even if it meant that Jensen had to act as the Volvo agent in their own factory and get the Pressed Steel in working order, according to the contract. Jensen would be compensated for all the costs, a reasonable sum for the overheads and a profit. It was decided to carry on with the negotiations a couple of days later, on November 9 in order to enable Jensen to run through a number of details that they had to look into. During the time between, both solicitors were asked to make a draft for a new deal. Still, Volvo suspected that Jensen would return with additional demands for compensation of production shortage

When they re-started on November 9, at 10.30 in the morning, the negotiations were held in the office of Mr. Wilson and two different suggestions for a contract had to be looked into, one from Volvo and one from Jensen Motors. For Volvo Mssrs Albrektsson, Darnfors, Helge Andersson and Mr. Garret were present. Representing Jensen Motors were their solicitor, the Jensen brothers and Mr. Conlif from Norcross. It all started with a debate regarding the sum of £100,000 for damages that Jensen had thought was going to be paid immediately, which hadn’t been done. This was caused by a misunderstanding on linguistic grounds and Jensen withdraw their demand for immediate payment. The the solicitors went to work with the deals. When the negotiation began again in the afternoon, after a tea break, Jensen again brought up the £100,000 causing irritation to spread around the table.

After that Jensen brought up a new matter, never touched on before, the Volvo payment for future claims. These were based on Jensen dropping the claims for damages if the actual sum was going to be lower than the one demanded. But now all of a sudden, Jensen started to argue about future compensation sums. At the final stage of the negotiations, the Jensen brothers and Mr. Conlif of Norcross took a stand against their legal representative who had previously agreed with Volvo’s Mr. Garrett a draft contract which regulated the £100,000. This meant an end to the meeting. Volvo was not willing to proceed any longer and the parties left the office. That also meant that the agreement for a rectification line became invalid but this was brought up at a later stage. Volvo asked for permission to tell president Engellau about what was said at the meeting and it would be he who would then reply to Jensen the following Monday, November 12.

On arrival in Gothenburg, Darnfors and Albrektsson went straight to the Engellau home, it was a Sunday morning, and for two hours related all that had happened in the office of the Jensen solicitors. Engellau at once replied that he was under no circumstances going to accept the new Jensen demands and commit himself for the future. Albrektsson and Darnfors stressed that Jensen had given a most unfavorable impression and was not trustworthy. When Engellau came to the office on Monday morning he made up his mind. Later that day, November 12, he summoned Ekström, Eriksson, Redvall, Lidmalm, Berthelius, Zetterström, Darnfors and Albrektsson to his office for a meeting. All present agreed that Jensen could not be trusted in the future but that the production had to continue up to a point where Volvo could take over the entire operation. Engellau would personally try to negotiate with the chairman of both Jensen Motors Ltd and Pressed Steel Co. Ltd. and try to dissolve the contract after car number 6,000 had been made, at the lowest possible level of damage. The maximum sum mentioned was £300,000 but £200,000 would be acceptable for Volvo. This was on the condition that Pressed Steel agreed to cut their production during the transition period in order to make it possible for Volvo to move the operations to Sweden. Redvall said that Volvo would need at least one year to start up the production in Gothenburg, unless it was possible to work with Jensen and take over material from them and their suppliers. After the meeting, Darnfors, Albrektsson and Castell went to work on getting all the documents that Engellau would need before he left for London.

AB Volvo breaks off the Jensen contract but carries on with Pressed steel Co ltd

Three days later, on the 15 of November Mr. Engellau was in London for two meetings at the Grosvenor House on Park Lane, the same hotel where Bengt Albrektsson had carried out the final negotiations with Pressed Steel an Jensen Motors in December 1958, before the start of it all. This time, however, the atmosphere was much different. After having checked the situation with Mr. Garrett, Engellau sat down at 10.00 am with the Norcross Ltd. chairman, Mr J.V. Sheffield. The meeting lasted for two hours and resulted in a final agreement which stipulated that Jensen was going to continue to build cars until the figure 6,000 (+- 50 cars) was reached. This meant that only some 900 cars remained up to chassis number 6,000, in parallel, Jensen was going to carry out additional work which Volvo was going to pay for according the the salary level agreed on, plus an additional 150 percent for the overhead costs and a profit. After 6,000 cars had been made, Jensen was going to cease the production of P1800 completely and Volvo would buy all material in the Jensen warehouse at their purchase price. Jensen was furthermore going to cooperate with Volvo, under full transparency, supplying Volvo with all necessary information regarding the suppliers and related costs. Upon signing the agreement, Volvo would pay Jensen the sum of £150,000 and additional £50,000 after the last car had been finished and delivered to Volvo. By that, the deal was closed and Jensen would have no rights whatsoever to any claims for damages from Volvo. The only condition that had to be met before the agreement could be signed was that Engellau must come to necessary solution with Pressed Steel later the same day.

At 3.00 pm that afternoon, president Engellau met with Mr. Abel Smith, chairman of Pressed Steel Co. Ltd and Mr. J.R. Edwards, Mr. D.D Hobday and Mr. T.P Stroud from the management. Engellau declared the the Jensen situation that prevailed could not continue, especially when all parties lost money on their contracts, and explained that he hoped that it would be possible to come to a solution with Jensen with regards to their claims without having to go to court. Engellau entered the negotiations with an attitude of wanting to save the P1800 production at all costs, that Volvo wanted to continue working with Pressed Steel and that the most important things now was that Pressed Steel agreed to lower their production rate in order not to flood the Jensen premises with bodies during the transition period.

The atmosphere was very positive, and Pressed Steel accepted to continue to deliver the bodies directly to Volvo. All the Volvo demands on Pressed Steel were met and accepted, also the claim for damages of £100,000 for the compensation of costs and losses caused by the Pressed Steel negligence to deliver bodies at a quantity and quality agreed on. This had, in fact, been accepted by Pressed Steel at an earlier stage and was now confirmed in writing. Engellau confirmed an additional order of 5,000 body shells and future orders from Olofström with regards to manufacturing tools. Pressed Steel expressed their appreciation of the straightforward and friendly relation that characterised the Pressed Steel and Volvo cooperation and had hopes of o fruitful future together

After the meting with Abel Smith, Engellau went directly to the telephone and called Mr Sheffield asking him to come for an evening meeting with Jensen representative, including the legal people from both sides. Mr. Garrett’s draft was gone through and there were additions made; within three months after the last car had been made by Jensen, all material was to have been removed by Volvo. A paragraph was included that, upon Volvo request, Jensen would continue to to manufacture smaller details in the future, but only up to number 10,000. On request from Engellau, Mr. Sheffield also promised to personally see to it that nobody from Jensen would cause any difficulties during the final stages of the operations but instead make it easier to conclude the operations as soon as possible.

At a meeting in his home in Gothenburg on November 19, president Engellau related all that had been said and agreed at the meetings during his London week, After that, he met with a number of people who in one way or the other were involved in the production of the P1800 and explained what had to be done next. At his meeting with Mr. Sheffield, Engellau promised to make a statement together with Jensen Motors Ltd which would be written in such a way that no party was to blame for what had happened, and that no shadow was cast on the car itself. One possible explanation for Volvo’s action could be the forthcoming Torslanda plant with all its capacity which would enable Volvo to achieve what was the original plan, to produce the car in Sweden.

This is the statement that communications director Hans Blenner at Volvo wrote in Engellau’s name:

| Communique’ regarding the VOLVO P1800 When Volvo started the manufacture of their sports car P1800, the company had no manufacturing capacity for this in their own works. For this reason the manufacture of the P1800 was partly handed over to Great Britain. It was however Volvos intention from the very beginning to produce the P1800 in Gothenburg as soon as the manufacturing resources made i possible. Thanks to the erection of the new Torslanda plant, the company will now get the resources to assemble this car in their own administration. According to agreement with the British manufacturer this production will, therefore, be removed from Great Britain to Sweden during 1963, and an agreement in this respect has been made with the British manufacturers *** 22.11.62 DI-GE/ibj |

Volvo also conveyed to the Norcross chairman, Mr. Sheffield, that Volvo did not expect any press release at this stage and officially mentioned as little as possible about the matter, strictly for business reasons. Volvo knew that once this became public knowledge, the demand for Jensen-built P1800 would decline rapidly with a price reduction as a consequence, before the Swedish-built cars would come on the market.

In the aftermath of these dramatic events, Bengt Albrektsson was responsible for the details of the new contracts together with representatives from the other party parties, and soon to be signed by Volvo and Jensen Motors. Among other things, Jensen wanted to included i piece that eased up the demands getting the last 900 cars ready by changing “as quickly as possible” to the more liberal “without reasonable delay”, which was accepted by Volvo. Jensen was also given the right to reject bodies that were not ok after they had been brought beyond “the white line” and that this happened after crossing “the white line” instead of earlier, These were only minor details.

The deal between Volvo and Jensen Motors Ltd dated November 20, 1962 was signed two days later by Gunnar Engellau as an appendix to the original head contract from January 31, 1959. After the approval and confirmation from J.V. Sheffield the deal was closed. It main contents were the following:

- Jensen Motors was going to produce 6,000 cars (minimum 5,590 and maximum 6,050) instead of the 10,000 previously agreed on and stated in the original contract and which also was also the number of component kits that had been ordered from suppliers, both Volvo and outside suppliers.

- Jensen Motors was going to do this without reasonable delays, and also carry out necessary corrective actions on the bodies supplied to them by Volvo. Volvo would establish control teams both in Linwood and at West Bromwich for this purpose. Volvo was going to fully pay for all such Jensen work,

- Volvo was going to take over all remaining P1800 material, components and parts from the Jensen warehouse and together, Jensen and Volvo would make a list of suppliers involved in order to make the purchasing process easier for Volvo in the future. Volvo was also going to be able to demand from Jensen to continue production of details used up to and including chassis number 10,000

- Volvo was to take over all tools, equipment, drawings and blueprints from Jensen and discontinue its entire operation at Jensen Motors within three months after car number 6,000 had been delivered.

- Volvo was, according to the agreement, to pay Jensen Motors the total sum of £200,000 on dissolving the P1800 contract;a compensation for breaking the contract in accordance with the the existing paragraph in the original contract.

The new deal with Pressed Steel was struck when Mssrs Hobday and Stroud went to Gothenburg the week after the London meeting. It was agreed on to cancel the original order from February 5, 1959 after 6,000 body shells but that it was going to be instantly replaced by a new order for 9,000 body shells (including front members) reaching body number 15,000 eventually. The body shells were to be delivered treated with Heavy Ensis Oil and two reference bodies were going to be made and placed in Linwood and in Gothenburg respectively to illustrate what kind of finish the companies had agreed on. The new order was finished on December 12 and was completed with two appendix parts, stating the precise details regarding the Volvo demands with regards to quality and inspection matters, and a special section about the use of tin and lead filling.

The appendix about specific quality and inspection matters stated that the body shells were going to be made according to the previous construction specifications, except in some areas which were going to be attended to at Volvo (fillings and soldering). Pressed Steel was going to raise its quality successively which would result in a reduced need for filler work. A man from Pressed Steel was going to come over to Gothenburg in order to make it easier to communicate and thereby improve the process. No less a person than Mr. W. Pritchard, well-known to all Volvo people who had been at Linwood, was selected for the job. Initially he was going to spend three months in Gothenburg, starting the same date as work started according to the contract and deliveries began. He became Volvo’s speaking partner on site regarding forthcoming needs for corrective actions and reported the production and quality situation to Linwood and Cowley once a week.

Volvo informed Pressed Steel that the need for bodies during 1963 was probably going to be around 100 per week and from 1964 some 150 bodies per week but here Engellau put in a reservation regarding the future. It all hung on the fact if the market potential of the P1800 had suffered from poor quality of the first 6,000 cars or not. Initially, Pressed Steel was going to deliver 25 bodies shells per week starting on January 14, 1963. In connection with this, Volvo mentioned that they had the intention to produce up to 30,000 cars in total. He also said that Volvo wanted Pressed Steel to deliver bodies of the agreed quality and quantity right from the start, according to the new contract, and if they succeeded, this could result in new Volvo orders but if they failed, it would mean the end of the cooperation, just like it had for Jensen.

Gunnar Engellau felt happy about how things had proceeded, like many of his management did, and in December 1962, all difficulties regarding cooperation, relations and quality problems with Jensen Motors seemed to have ended. It must have come as a relief to both parties that the whole matter was solved without bringing each other to court. Mr. Garrett shared this opinion with his Swedish client but nevertheless told Engellau that now, after everything had been settled, he felt a bit disappointed over the fact that Pressed Steel Co. Ltd had got out of the mess too easy. Volvo was still left with the basic problem, the body manufacturing at Linwood. But now, the whole responsibility rested on Volvo themselves and the date for the transfer to Sweden came closer and closer at an great speed.

Uno Gunnelid worked with planning and projects at Volvo. He says that the day after the deal with Jensen had been finally closed, Engellau’s secretary called him and asked him to come to Engellau’s office at once. This meant entering a management team meeting and Gunnelid was told that the contract with Jensen had been broken, that Volvo now gave top priority to secure the transition of the P1800 production from Britain to Sweden and to do this as soon as possible. Gunnelid was then ordered to go to West Bromwich on November 26 together with Engellau. His mission was to organize the bringing home of the entire assembly operation and to keep an eye on the economical side of the deal. Gunnar Engellau was clear “And do remember that starting from January 1st 1963, there must be 100 complete kits of material for the P1800 in Gothenburg” A difficult task, but not impossible one to fulfill. He had been around for some time and knew what to do. But he needed a good team for his job and he knew where to find the right people. He went straight to the purchasing managers Lars Wahlström and Anders Kruger who joined at once, as did the chief delivery inspector, Sigvard Noreen

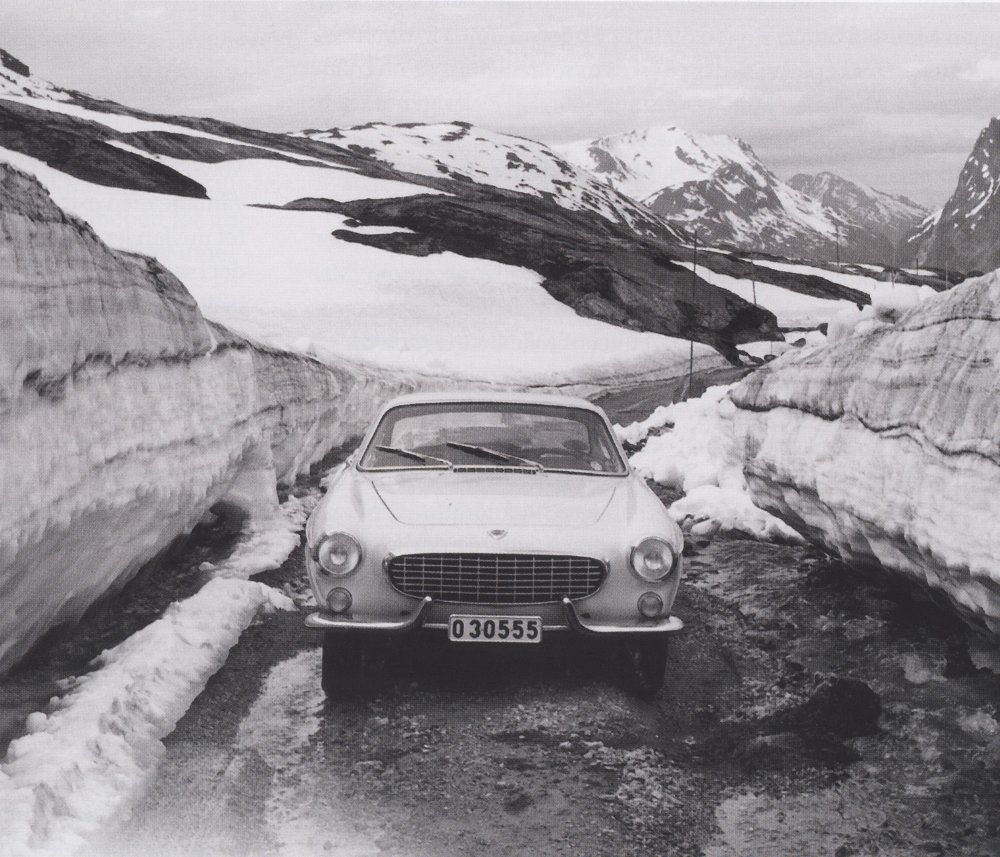

From West Bromwich to Lundby

The work of getting the production out of West Bromwich and over to Sweden had started in 1961 and continued during 1962 under the leadership of Åke Zetterström. This happened in parallel to the contacts and negotiations with both Jensen Motors Ltd. and Pressed Steel Co. Ltd. in order to solve the problems with the ongoing production. Volvo made thorough specification for a Swedish built P1800 and did a cost analysis and compared the result with a Jensen built car. For the calculations, Volvo used an initial production of 10,000 cars and that the new tools that had to be made were going to be paid for when 3,000 cars were reached. The design and engineering department looked into the relation between the need for modifications against low start-up costs.

The product department was led by Gunnar Ehrenström and they studied what was needed from a product perspective, i.e. a customer perspective. They found that the engines needed to have an increased power output, somewhere in the region of 120 to 125 hp in order to make the car reach a top speed of 180 kph (112 mph) and reach 100 kph from standstill in 10 seconds. This, however, did not at all appeal to Svante Simonsson since these figures could not be reached using the B18 engine and 97 octane fuel but needed a 2 litre engine. Such an engine was not yet going to be launched – the current transmissions used in Volvo cars could not cope with the extra power of such an engine and would require a lot of work before that could be realized. There was also a request for new wheels that would lend the car a more exclusive and lighter look. The department suggested the removal of the front quarter lights and instead fit rear openable quarter lights and in order to improve the leak situation, fit a window frame to the doors. None of these suggestion were realized. There was also references to the hockey stick on the door which people had criticised by saying that it just made the car look dated and accentuated the rear fins. A suggestion was made to let the styling department look into this. Other areas of improvements (their opinion) concerned grille and bumpers, colours and trim. One suggestion that was put forward (but never realized) in order to boost sales was to introduce a limited edition GT version, just 100 cars or so. This had been suggested before and duly rejected. This time the GT car was going to have a highly tuned engine, be of lightweight construction with aluminium body parts, a more racy interior and perspex window instead of glass. At the end of 1962, the product department made a sales forecast for the P1800 for approximately 5,000 cars per year. This , however, was not going to happen until 1973, during the car’s last year of production.

The production department worked with evaluating all alternatives for the manufacturing of bodies and though the shortage of production at Jensen and Pressed Steel, their deadline wasn’t until September 1, 1962. When September came, it was seen as possible to begin production of a Swedish P1800 starting from chassis number 10,001. Concerning paint, the supplier ICI advised Volvo not to use the silver metallic paint in production. The new white colour was on the other hand to be introduced beginning with chassis number 6001. Svante Simonsson also brought up the question of a convertible version but this was dismissed by the sales department. They also stressed the fact that the production of cars above number 10,000 had to be made in Sweden and that painting, rust proofing, sealing and quality in general had to be carried out according to the Volvo standard for all other cars. Per Eriksson said that if it was possible to do it, he would prefer a simpler and cheaper front bumper, re-designed if necessary. Changes were also requested for hub caps, rim embellisher and the spare wheel.

Volvo determined that in the future. Pressed Steel would supply complete body shells to Volvo that could be used for the building of a first-class sports car. Five bodies had already been ordered from Pressed Steel in order to be used for adjustments and paint tests in Gothenburg. Svante Simonsson planned to go to Linwood by the end of September or early October in order to talk about body shells for Sweden, which meant that a final decision about the future production of the bodies would be made during October. Using September as a reference month, it was calculated that 10,000 cars ought to have been finished at Jensen by July 1, 1963, give or take a month.

During the month of October, the Volvo management also planned to make the decision for a possible production of additional cars after the 10,000 level. At the same time discussion were carried on with Pressed Steel about the current situation and Volvo realised that in order to push the production beyond 10,000 cars, Pressed Steel would have to produce the bodies because there was still no capacity available in Sweden. Gunnar Engellau was, however, already in September clear that the Jensen cooperation had to stop but this was not to be known until a much later stage. He pointed out to Mr Garrett that everything in his power had to be used in order to avoid a legal process against Pressed Steel because that would probably cause them to decide not to work with Volvo in the future and this would mean the end of the P1800, If there were no alternative but to act, this had to be considered carefully from every angle before the solicitors went to work.

Volvo sat down and went through all the little details of the original contract in order to find out how the best possible set-up for the future should be organized if Volvo was to take over the production of the P1800. One important issue was how Volvo could use Jensen’s suppliers and deal with them directly. According to the contract, Jensen’s responsibility for keeping up the supply of parts and components would cease at the same time as the deal was cancelled, but they were under obligation to list which suppliers they had used. There was also a paragraph that stated that once the deal was cancelled, all stocks of supplies and material at the sub-suppliers were to be taken over by Volvo. Although the original contract was about the assembly of 10,000 cars, there was nothing that granted Jensen the exclusive right to sell spare parts after these cars. Concerning tools and special equipment, Volvo had the full tight of their disposition, no matter were they were located, including those at the suppliers.

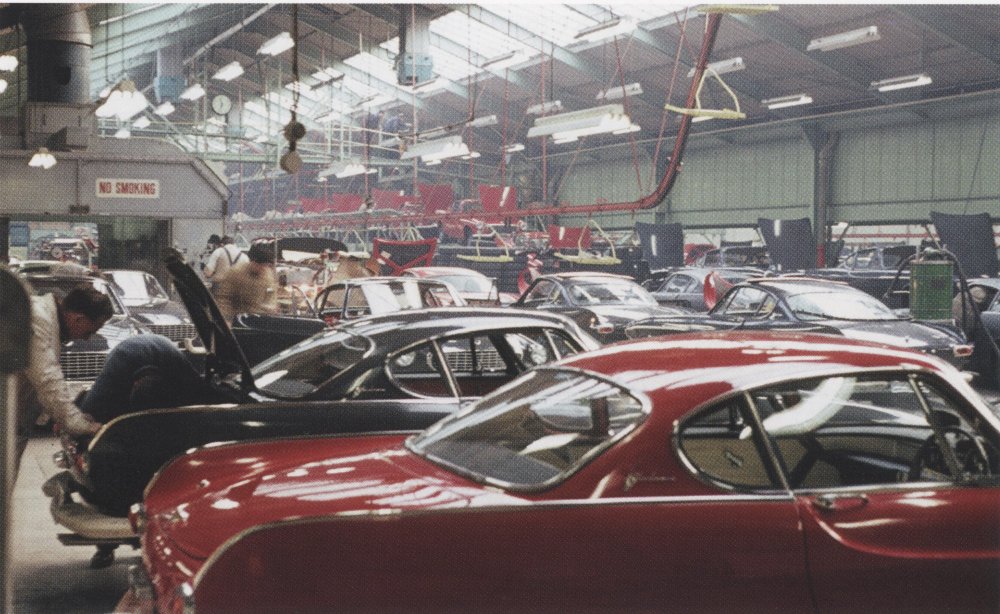

Towards the end of 1962, Benny Borsing was involved in the work of constructing a try-out assembly line for the P1800 in the Lundby plant, Benny tells:“I was called to see my boss along with some other colleagues and we were informed that they were going to start a new project. We were given some information about what was planned and then shown an area in the plant where they were going to work. We were going to build a prototype, not for a car but for an assembly line that could be disassembled again and moved to the new Torslanda plant and built up again” This, however, did not happen because when the P1800 went into production in Gothenburg in 1963, it was in the Lundby plant. Borsing recalls that ten cars was assembled by hand along the try-out line. They arrived in kits, crates filled with parts, empty body shells and the rest in boxes and bags. The try-out setup was one of trial and error; the parts were positioned along the line in a logical order, we re-arranged, tried again, until the whole operation became rational and efficient enough. It all started with the parts that were fitted inside the car. The body shells were placed on trolleys which we rolled by hand along the line, through the different assembling stations. It was all very manual labour, no conveyor belt, guiding rail or moving line. The line itself was U-shaped. The body entered through a gate on one side and was pushed along, being fitted with parts along the way. It was also important to keep an eye on the assembly quality, that everything was fitted correctly. Those bits that did not was reported. After having traveled through the U , the car was supposed to be finished. The ambition with this try-out line was to learn how the car was built in the best possible way, in what order the parts were fitted to the car, how the parts were brought into the factory and how much adjustment the car had to be exposed to.

The transfer of the production

Having agreed with Jensen to stop the production at 6,000 instead of 10,000 which was decided in November 1962, Volvo geared up its preparatory work for the next phase of the process – the transfer to Sweden and the plans to have the production running by early 1963. Volvo had decided that the car was going to have the same specifications from chassis number 6001 as it had up to 6000, except for changes that had already been decided; a modified engine, new upholstery combinations, (305 and 306). From chassis number 8000 a new rear seat was to be introduced, so were new front seats with adjustment mechanism and a new system for the fitting of the headlining. The first series of the P1800S (S for Sweden) was planned to be 4000 cars. ten cars were to be part of the try-out series during January 1963, of which two cars were going to be RHD, The start of production was planned for the first week of February 1963, with an initial rate of 25 cars per week, successively rising to 50 cars at the beginning of March, reaching 100 cars per week by mid-April, Easter time

The practical work of preparing the transfer of the production to Gothenburg was going on at full speed. Some of the most active people in this were Uno Gunnelid, Lars Wahlström, Anders Kruger, Sigvard Norin, Lennart Lindgren and Ingvar Svennung. During their trips to West Bromwich, they always stayed at the Raven hotel in Droitwich, which was also the favorite waterhole for the local golf an polo players. They all worked at Jensen with the Volvo matters in periods during the later part of 1962 and the early months of 1963. The purchasers’ role was was very important one. It was necessary to get a picture of the total flow of material and details needed for the assembly in order to decide which suppliers to use also for the forthcoming production and which suppliers to replace with new ones, maybe in other countries. Lennart Lindgren stayed at Jensen for six to seven weeks each time and was responsible for mapping out all details that formed the foundation for the design/engineering information and register every single item and organize them in groups. This was of utmost importance for the re-start of the production in Sweden because it was necessary to find out very quickly where to purchase details needed. Lindgren delivered his work to the purchasing department who went to work with finding the best suppliers.

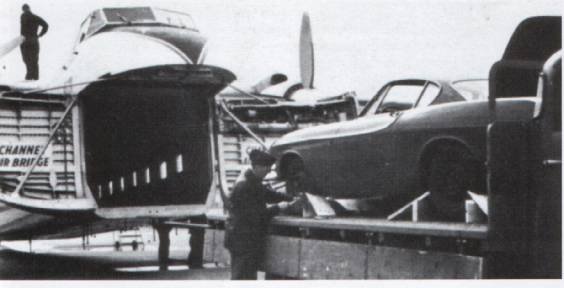

The situation at Jensen became a bit tense shortly before Christmas 1962. There was a short break break over the Christmas days (Christmas Day was a Wednesday) but the work started again as soon as Christmas was over. On December 31, two fully-loaded air freighters departed for Gothenburg. They carried production equipment and components for the P1800. At the same time a passenger aircraft left Britain with Uno Gunnelid onboard. After having landed at the Torslanda airport, he saw the freighters coming in for landing and politely asked the airport officials for permission to enter the strip in order to greet them and inspect the cargo which was granted. Since it was New Year’s Eve, everyone was in a hurry and the cargo was quickly unloaded and brought to Volvo on trucks. There they parked, locked the trucks and the gates and everyone went home to greet 1963 which was due in a few hours. On January 2, everything was back to normal and the Swedish P1800 operation began.

Another Volvo man who as heavily involved in the work of closing down the British P1800 operation was Helge Andersson, who spent the last week of February and the first week of March 1963 in West Bromwich. As part of the discontinuation, Volvo paid all bills for body panel and other additional work while in return receiving the guarantee sum (customs deposition) of £2.000 which Volvo had put to Jensen’s disposal long ago. By mid-March, all tools were brought together and shipped to Sweden. Helge noticed that the list of all the items that had been given to him by Jensen was correct. By the end of the month, the Volvo warehouse on Kelvin Way was empty and Helge Andersson’s work with the P1800 in Britain was over. Lennart Lindgren and Sven-Olof Andersson were busy with the equipment that had been bought and paid for by Volvo, and that was needed for the assembly. It was dismantled, packed and shipped to Sweden, along with fixtures, jigs and jig attachments. Jensen had a small supply of parts for the car left. Some of it was also brought to Sweden and some of it was scrapped.

The Raven Hotel in Droitwich was a popular place for the Swedish Volvo people. A dinner and dance was arranged every Saturday evening and for which the local beauties were invited by Mr. Platts, the proprietor, if there was a shortage of ladies. The dancing started in the dining room after dinner. The tables were put aside along the walls and a small orchestra entered the bandstand. Next to the dining room was a small ballroom for private parties, and that is exactly where Mr. Platts arranged for specially invited guests after the music had stopped. S-O Andersson was a regular guest at these late night parties The picture below was taken in 1963 when Lennart Lindgren was there too. He played the piano and sang, much to the amusement of the ladies.

During the spring of 1963, the work continues and Uno Gunnelid had continuous and very positive contacts with the Jensen financial director an a number of key people in different positions. The discontinuation period lasted between January and May 1963. Gunnelid’s team worked closely with other Volvo people, for instance Arne Hasselsjö’s team for quality control and S-O Andersson who was production specialist. It was a difficult situation; to close down one production operation and start up another one hundreds of miles away. Uno Gunnelid confirms that it meant a lot of work, few eight-hour working days, but on the whole everything went well. It even worked better than expected, a work characterised by professionalism and friendship.

By the end of February, 115 cars remained to be finished, 95 of them were RHD, and 49 cars were yet to be built. The stock of cars by the 10 of March consisted of some 60 cars in the Nordic countries, some 80-90 in Europe and another 770 cars in the US. These cars, together with cars under way, were estimated to cover the demands for cars until mid-May. The very last P1800 to be finished at Jensen, chassis number 6000, was reported ready on February 20, 1963 and was shipped on March 9. The last Jensen shipment for the USA was made up of 90 cars and was noted for delivery on February 23, 1963. Sven-Olof Andersson recalls that the Jensen personnel were very effective during these last days of production (!). He stayed behind after the last car had been built and a few minutes after the car had left the assembly line, the whole place was nice and tidy, no traces of the P1800 remained. Sven-Olof Andersson and Lennart Lindgren were the last Swedes to leave Jensen and check out of the Raven Hotel. This time it was for good.

The first cars are built at Lundby

Volvo dragged on with the issue of information about the breakup of the Jensen relations and the Swedish plans. In January 1963, this was still more or less a secret on both sides of the North sea., which was a bit surprising but good for Volvo. Engellau began to hear from dealers who wanted to spread the news as soon as possible for the benefit of the sales. The earliest date of publication of the information to the general public had been set to April 15 by Per Eriksson. Engellau was most eager to wait and use the time for careful planning of market activities. A bonus on the Jensen cars was maybe one answer to help get rid of these cars in as many markets as possible before the Swedish-built cars were introduced.

Such an action was determined on basis of the sales situation for the cars during January to March, and how well Bengt Darnfors succeeded in his work of getting the Swedish production running. At the beginning of February, a story appeared in an American paper stated that Volvo was bringing the production of P1800 to Sweden. Volvo was in a difficult situation from a timing point of view. The Geneva Motor Show was going to be opened on March 10 – which would have given the new P1800S a tremendous start in life – but due to the current supply and delivery situation, it would have been too early to show the car there, unless the press ‘forced’ Volvo to do it.

The first test drive report on a Swedish-built P1800S was the one made by Gunnar Engellau himself. The date is February 8 1963 and Engellau had the following to say: “I have now tried a car built by ourselves and it made a very nice impression and had a much better overall finish than that of the Jensen cars. There are still things to improve, however, which I have told Darnfors and Vallin”. He was so happy with the car that he wanted to ship some cars right away to selected US and European dealers in order to stimulate them and have them to prepare themselves for sales of a new and better car.

Jens Larsson started to work at Volvo at the age of 19, in the spring of 1963. At this time, the assembly of the P1800S was slowly getting ready to start and Larsson felt that the Lundby plant was no longer in focus because the forthcoming transfer of activities to the new Torslanda plant was keeping Volvo busy. At Lundby, the P1800S was assembled in the same building as the Amazon. Besides Larsson, who represented the young generation, their were many faithful old workers making P1800S, The Amazon production was run in shift but the PV544 and P1800S production were carried out during daytime. The tempo was was a modest one on the line since the Amazon production was given priority, If for instance, there were any part shortages for the Amazon, the 1800 line was stopped and the parts that fitted and could be used, were used for the Amazon instead. This way of handling things led to the fact that the 1800 cars sometimes had to be finished during the weekends and that one car could take weeks to build. Another example was that if there were people absent from the Amazon line, the 1800 line was halted and people had to walk over to the Amazon line and continue their work there.

The layout of the Lundby plant was fairly simple but effective. The PV and the Amazons were made in different buildings. In the far end of the Amazon plant there was a section called the “sports hall” where once the Volvo Sport had been assembled but standing empty and was now used for the P1800S. On the floor there were a U-section of steel girders laid out in parallel to form a track on which trolleys rolled. These trolleys were made up from tubular steel, like jigs, on which the body shells were fitted. The trolleys, pushed by hand, carried the bodies all along the assembly line. At the end of the line, the body was hoisted in order to lower it on to the chassis and fit a large sub-assembly made up from the front suspension. the engine and the transmission. The rear axle (which had been assembled in the Amazon section), parking brake and the exhaust system were fitted to the car at this stage. This station was designed like a bridge, but was referred to as “the pit” One man was standing in the pit below the car fitting large components like the rear suspension and another one fitted parts to the car from the bridge above him. The bodies were painted in another building and to get them there, they were loaded on carts and pulled by a tractor to the paint shop. In total some 20 to 30 people worked with the P1800S assembly, led by a man called Thorin.

When the car was ready, a control inspector brought out the car in to the backyard and drove it around the building. There, the car was driven up to a platform where the steering wheel was adjusted, getting the spokes in neutral horizontal position. The car was the taken to the “Z2” on the other side of the street where the final inspection took place.The Lundby plant was in the middle of a built up residential area and the layout was a bit awkward, To check the car for leaks, it was run through a water test where it was soaked in water. As far as Larsson recalls, there were no particular problems with the cars, and they did not leak. Before he joined Volvo, he had become an eye witness to how Volvo had parked some of the “whisky cars” from the Channel incident on their premises, under cover and without knowing the real reason behind this. He also recalls that Engellau had ordered a P1800S for himself and Larsson was involved in the assembly and so was a specially assigned controller in order to build it to perfection. When the transmission chassis member was mounted on the cars, the use of mild force was necessary in order to fit the bolts. This was not to be done on Engellau’s car. Instead, the member was carefully adjusted in order to make the bolts fit perfectly. This car was painted in his personal “Engellau blue” with black leather interior.. The car, model year 1963, had chassis number 6717.

In February 1963, Engellau asked Tor Berthelius to select a white Swedish built car with overdrive and without delay send it to Paris, to the Facel S.A. company. They had been in touch with Volvo about making a convertible version of the P1800S and were now supplied with a car for that purpose. Facel’s main business was body manufacturing and pressed components – like Pressed Steel – and their car production a mere hobby, although a very costly one. Facel had developed a body reinforcement with unitary construction. President Engellau asked them to build such a convertible but it is not clear what really happened. It was probably cancelled in the connection with the B18 engine deliveries from Volvo to Facel (for their Facellia car) which ended due to financial difficulties, and Facel stopped making cars in 1964. The question however remains: How far did Facel get in the work of making a Volvo P1800S convertible?

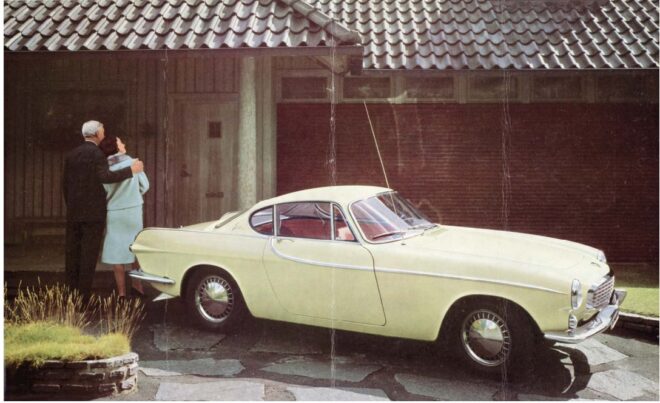

The Swedish built Volvo P1800S is launched

On March 9, Engellau decided that the introduction of the P1800S was going to take place in Sweden, in Scandinavia and the rest of Europe after the Easter holiday, April 16 to 20. On the Overseas markets the car was launched an May 1 and a week later in North America. Already on March 29, 1,00 PM, Volvo made a secret static presentation for the motoring press in a fashionable Stockholm restaurant, the Ulriksdal tavern. Two car were shown and the event had been staged by Hans Blenner and Hubert Burman. The choice of Stockolm was based on the fact that if the car was shown in its home town of Gothenburg, local papers would find this out and leak the news before the publication date, which was not desired. After the Stockholm presentation, the cars were immediately taken back to Gothenburg.

The first 2000 cars to be built at Lundby were of the so-called Type B but built by the same specifications as the Jensen cars, except for some minor differences. During the first week of February, 84 bodies arrived from Pressed Steel.The cars with chassis numbers 6001, 6002, 6003, 6004, 6005, 6006, 6007, 6008, 6009 and 6010 were try-out cars and the subsequent 6011, 6012 and 6013 was used for paint tests.